Herbicide Drift: EPA’s Weak Dicamba Regulations Ensure the Damage in 2018 Will be Widespread

Steve Smith

Editor’s note: Herbicides used to kill weeds before they emerge from the soil are known as “pre-emergents.” Herbicides applied to crops after weeds have already sprouted are called “post-emergents.” Dicamba-based herbicides kill broadleaf weeds and woody plants both ways — pre- and post-emergent — by affecting the growth of the plants’ vascular tissue. They also kill or damage countless other plant species that are not genetically engineered to tolerate them.

On October 13, an EPA press release announced the agency’s decision to allow the use of dicamba herbicides during the 2018 growing season for post-emergent weed control in genetically engineered, dicamba-resistant soybeans and cotton. Prior to crop year 2017, there were no registered post-emergent uses of dicamba on any crops — GMO or conventional. The first labels authorizing post-emergent applications of the new, supposedly less volatile formulations of dicamba were issued in mid-November of last year.

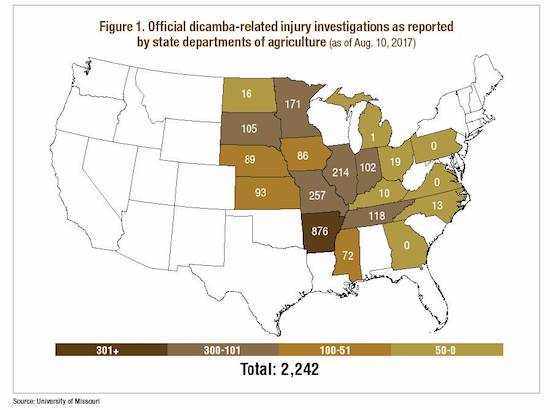

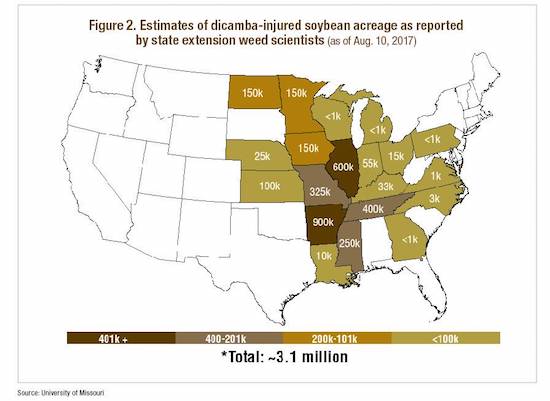

Serious crop damage problems from dicamba drift and volatilization occurred in 2017 throughout the Southeastern and Midwestern United States, impacting many million acres. Both state regulators and the EPA have been debating for nearly a year what restrictions, if any, to place on post-emergent dicamba use in 2018. In its October announcement, the EPA discusses its work with dicamba registrants to craft a set of uncontested, post-emergent label changes that will be enforced in 2018. The most important include:

- Post-emergent dicamba herbicides will be classified as “restricted use,” requiring that applicators must be certified (or work under the supervision of a certified applicator);

- Applicators/farmers must receive special training, and maintain more detailed records of when, where, and under what atmospheric circumstances applications are made;

- Applications are limited to when maximum wind speeds are below 10 miles per hour (mph) (down from 15 mph);

- Reducing the times during the day when applications can be made; and

- More rigorous tank-clean out requirements to prevent cross contamination.

Before commenting on the substance of the EPA decision, I thought I would review what we learned in 2017, because those who fail to learn from history are destined to repeat it.

We confidently knew, and reported repeatedly, that despite the new formulations intended to reduce volatility, dicamba is uncontrollable due to its tendency to volatilize and move into areas where it was not meant to go. But now we have the science behind our proclamations. The University of Arkansas has determined that while the rate of volatility might be different in the initial 24-hours following application of the new formulations, over a few days the total amount of volatility was not all that different than the older formulations.

This came as quite a shock to the proponents of the new “safer” formulations. But seeing how Monsanto contractually prevented university researchers from testing the compounds for volatility prior to their approval, this finding that the new formulations only alter the timing of volatilization — not the amount that volatilizes — reinforces how dangerous dicamba truly is to any sensitive crops, vines, or trees growing within a couple miles. If conditions are right (i.e. a severe storm accompanied by tornadoes), dicamba drift can cover even greater distances.

(Source: agnewsfeed.com)

In 2012, Save Our Crops Coalition (SOCC) petitioned the EPA for an Environmental Impact Study (EIS) to determine the environmental effects of widespread planting of dicamba-resistant crops and the associated increased use of dicamba herbicide. We were ahead of our time.

There is now ample evidence that dicamba drift — a condition also referred to as “atmospheric loading” — occurred in Arkansas this year. The basis of our petition, which was granted in 2013 and finalized in 2016 (at which time the EPA erroneously concluded that there were no concerns), was that with widespread use of dicamba, we would be seeing a phenomenon that we had never seen before. That is, a local environment so filled with dicamba vapor that it would damage all susceptible plants in an area.

Specialty crops like the tomatoes Red Gold processes are especially vulnerable to damage by dicamba drift. The tomato “leaf curling” evident above is caused by low-level exposure to dicamba herbicide. (Image: Independent Science News)

In addition, when a given crop field or orchard is damaged, it will generally not be possible to determine the point source of the dicamba because it could have originated from several miles away. Hence the euphemism of the “blob that ate Tokyo” that SOCC has repeatedly used to describe the situation. We now know that SOCC was right to highlight the difficulty in determining the source of dicamba triggering crop or tree damage. We also know that proving causality will again be very difficult and more widespread in crop year 2018, due to the increase in acreage planted with dicamba-resistant crops.

(Source: agnewsfeed.com)

SOCC negotiated with Monsanto and BASF to achieve our label protections requiring that the wind be blowing away from certain specialty crops. It was a major and hard-fought concession from Monsanto, who was on the record repeatedly proclaiming it wasn’t necessary. From the start of our discussions, BASF was more willing to acknowledge and address the risk of off-target movement. In the case of the crop we’re involved with — processing tomatoes — we worked very hard to make sure that neighbors knew where our crop was located, and that if they damaged our crop, there would be a tremendous price to pay.

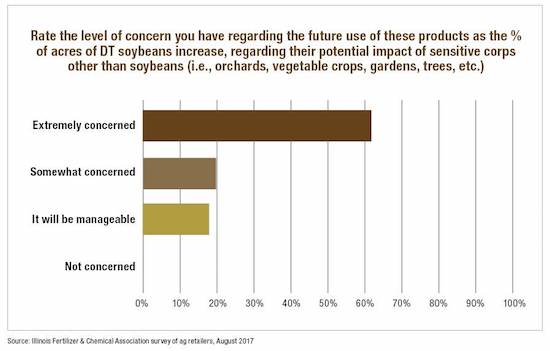

Red Gold and its growers escaped the season with no significant dicamba problems because of that attention. Other specialty crop growers were not so lucky. With the projected soybean seed market penetration for 2018 at levels approaching 70 percent for dicamba-resistant and 2,4-D resistant soybeans, the damage potential will be extreme for all sensitive crops. Off-target movement and exposure to sensitive plants and trees next year will be much greater.

Also unfortunately, we know from past experience that not all applicators are willing, able, or concerned about following label directions and restrictions. Plus, mistakes happen and their cumulative impact in 2018 will likely be much greater than in 2017, despite the EPA’s recently announced label changes.

Last year taught us that some growers would willingly not follow label directions and rules, since there were no dicamba labels authorizing post-emergence dicamba applications on any soybeans or cotton. With wishful thinking, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) had deregulated dicamba-resistant seeds, and Monsanto and Pioneer began commercial sales in the winter and spring, prior to the 2016 growing season. Plus, dicamba herbicide registrants (especially Monsanto) promised growers that necessary approvals would be granted by the EPA in time to allow post-emergent applications of the new, supposedly low-volatility dicamba formulations. But these registrations did not happen until mid-November of 2016 — months after the last illegal dicamba applications had been made.

A video explaining the use of dicamba herbicides, off-target crop damage and the government’s response to complaints throughout the 2016 and 2017 growing seasons. (Source: Dicamba Watch / Rachel Benbrook / Vimeo)

The massive extent of crop damage in 2017 proved, unfortunately, that the new, supposedly low-volatility formulations did not perform as advertised. Even the strict, lengthy restrictions on when, where, and how dicamba can be applied post-emergence were not effective in preventing off-target movement and damage to millions of acres of non-target plants and trees. A lengthy list of use restrictions, specifying when applications can legally be made, are now on the new EPA-approved dicamba labels. The most important variables addressed are wind speed and direction, proximity to sensitive crops, weed size, rainfall patterns and the nozzles used to spray.

One of the rules most egregiously broken in 2017 calls for weeds to be sprayed prior to reaching 4 inches high. My observations would be that the applicators must have misread that rule and thought it was 4 feet high. This later post-emergent spraying will ultimately cause a resistance problem with dicamba much earlier than predicted (i.e., within a few years, instead of five to eight). Going forward with the new EPA label restrictions and rules, we will once again be dependent upon applicators following the rules that they have demonstrated in the past they are either not able, or not willing to follow.

Arkansas has it right, assuming their proposed rule of no in-season applications is finalized, in recognizing that the nature of dicamba is uncontrollable no matter the care and efforts of applicators. Research conducted in 2017 estimated the number of available spray days during which an applicator would be in full compliance with all label rules. During the prime dicamba spray season there was, on average, only a few days per week when dicamba could be sprayed post-emergence and in accord with all label restrictions — not nearly enough time for many growers to cover the acreage they had planted with dicamba-resistant seeds. With the new additional restrictions, on-label spray days will be even fewer, forcing the hand of applicators to make applications outside of label guidelines. For some odd reason, the EPA seems to believe the new restrictions will both be fully adhered to, and successful in reducing volatility in 2018. History would suggest otherwise.

Label directions and restrictions for new dicamba herbicides (such as Monsanto’s Xtendimax) are lengthy and complex, and pose challenges for farmers and applicators striving to remain in compliance with them. (Image: Independent Science News)

There was always a fear that with widespread crop injury, the crop insurance industry might in the future refuse to provide coverage for dicamba injury, and that those injured would have no recourse to collect their damages. We were right, but also wrong — it was not in the future, it already happened this year.

In Illinois, the Farm Bureau Insurance system has denied all dicamba claims that didn’t involve direct drift. As a practical matter, I am told that almost all crop-damage claims arise, at least in part, from volatility movement. As a result, impacted farmers are getting no compensation. This borders on insurance fraud and is unconscionable. Apparently, if Farm Bureau Insurance is told that an applicator followed the label guidelines, they are denying all claims. Family farms will feel this effect, and with the financial stress on farms with today’s low commodity prices, it may cost some of them their farms.

A 2017 survey of ag retailers finds growing concern over dicamba cross contamination. (Source: agnewsfeed.com)

One of the many warnings that the SOCC has continually repeated is that it is not only crops that will be damaged by dicamba. This has become extremely apparent, and will give agriculture a “black-eye.” When rural homeowners begin to see their gardens and landscaping destroyed, the negative reactions will spread far beyond the discussions that are currently taking place within the agricultural community. It will become a public policy debacle that might affect the safe and approved use of all crop protectants in the future. Pollinator habitats will be affected, drawing attention from groups who do not normally get involved in herbicide decisions and discussions. The chemical pruning of fence rows is potentially a real problem, as habitat for pollinators and other beneficial insects is impaired.

Additionally, evidence is mounting of significant dicamba-casued damage to trees in 2017. (On my travels last year it was very easy to observe tree damage anywhere dicamba was used. I’m sure many homeowners looked at their trees and scratched their heads wondering what was wrong with them, not having any idea about the dicamba applications that had occurred nearby two or more weeks previously.)

In our own area, there is a small rural church where their trees appear to be severely injured, but I’m sure the congregation has no idea about why or what is happening. If we think the problem is bad now, then hold onto your hats for its widespread use in 2018 and the push back that is bound to come from outside — and inside — the agricultural community. The litigation carousel is now starting. It began with the Missouri peach orchard damage episode in 2016. The class action suits are coming fast and furious. What can’t be taken care of from a regulatory standpoint could eventually be taken care of, at least to some extent, from an economic standpoint. But at what cost to individuals and rural communities?

In 2016, the illegal use of dicamba-based spraying on nearby farms damaged tens of thousands of peach trees in Missouri when the volatile herbicide spread. (Image: Kade McBroom / nationofchange.org)

To complete my list of lessons learned in 2017, Monsanto will continue to give lip service to their dicamba stewardship plans — plans they too often fail to back up with action. If you ever get the chance to speak with a representative, ask them this simple question: “How many technical use agreements with growers or applicators did Monsanto cancel in 2017 because of off-label applications in 2016?” I could venture a guess, but I think you get the point.

The EPA failed agriculture miserably in their October 13 ruling. The SOCC was not alone in repeatedly recommending that the EPA disallow any in-season dicamba applications. While we appreciate the better-late-than-never “restricted use” designation, it is now clear that dicamba is uncontrollable in an environment of high temperatures and atmospheric conditions that promote volatility. Unfortunately, such conditions frequently occur in the MidWest and MidSouth regions from mid-April through mid-July.

(“Dicamba Herbicide Drift: A Disaster in 2017, Will Be Much Worse in 2018” was originally published on Independent Science News and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission. Maps, graphs and some images were added. To view the EPA’s October 13 press release announcing its decision to allow the use of dicamba herbicides in the 2018 growing season, click here. To learn more about the Save Our Crops Coalition, click here.)

I hope you found this article important. Before you leave, I want to ask you to consider supporting our work with a donation. In These Times needs readers like you to help sustain our mission. We don’t depend on—or want—corporate advertising or deep-pocketed billionaires to fund our journalism. We’re supported by you, the reader, so we can focus on covering the issues that matter most to the progressive movement without fear or compromise.

Our work isn’t hidden behind a paywall because of people like you who support our journalism. We want to keep it that way. If you value the work we do and the movements we cover, please consider donating to In These Times.