|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

Around the time the Democrats opened their convention at the Staples Center downtown, Margarita Reyes and her husband, Carlos, were catching an afternoon sandwich inside the tiny shoe and clothing store they own near the intersection of

It was at Florence and Normandie in April 1992 that a crowd of angry blacks gathered after hearing that a Simi Valley jury had acquitted the cops who were caught on videotape brutally beating Rodney King. What followed was the nation's worst riot of the 20th century. By the time it was over, the arson and looting had spread throughout this sprawling city, more than 50 people were dead and thousands had been arrested. I spent several days back then reporting from the middle of those riots, interviewing looters as they carried off their wares, people fighting to defend their homes and businesses, cops trying to keep the peace, and residents so enraged at the verdict that peace no longer mattered. An enormous sadness fell over me as I wandered through streets so thick with smoke you could barely see, past the ruins of entire shopping centers, and as I talked to stunned families trying to salvage a few possessions from their burned-down homes. Even before the rioting, this had been a neighborhood beset by drug trafficking and violence, long abandoned by the scores of factories that once provided its residents with jobs and some measure of hope. At the time, the rest of the country saw it as a black riot, even though the biggest group of people arrested during the disturbances was Hispanic, most of them immigrants picked up by police and National Guard troops for violating curfew or petty looting. South Central, like the rest of this city, and like so much of our nation, was a place undergoing a startling transformation. It was not only poor, but longtime black residents were moving out and being rapidly replaced by Mexican and Central American immigrants - newcomers fleeing a poverty and desperation in their homelands that could make the worst ghetto in this country seem like paradise. Only eight years later, that transformation is even more pronounced. You see it in the businesses around Florence and Normandie. Margarita Reyes, who is from El Salvador, and her husband, who is from Guatemala, opened their store only three months ago. Up the street is the Cuba/Mexico Night Club. There is Pancho's convenience store, and Rosa's Party Supplies, and Hilda's Hair Salon, and Club Las

Paul Mauldin, a black man and longtime resident, was busy repairing an engine at the Baby I'm Back Auto Care Shop, just down the street from the Reyes' clothing store. Mauldin, 47, moved to Los Angeles from Tyler, Texas in 1977. "All the blacks are moving to Riverside or San Bernardino," he says. "Nothing but Spanish moving in." Not much has improved in South Central for either group since the riot. Most of those who had no insurance when their homes and businesses were destroyed have fled. Any progress has come from those who stayed to rebuild, and from the new immigrants, who were glad for a chance to buy or rent an abandoned store at a cheap price. City Hall and the politicians in Washington didn't put much money into the neighborhood. "You see any new housing since the riot?" asks George Stevens, a retired city worker whose family has lived in South Central for 50 years. "Nothing's changed for the poor man." After decades of broken promises, local blacks are deeply bitter. They seethe at a Clinton-era prosperity that whizzed past South Central like traffic on the freeway. I asked Mauldin about the Democrats and the convention downtown. "I don't pay them no mind," he says. "Never voted in my life. Never heard one of them say something made me want to." The Latino newcomers, on the other hand, haven't had time to become disillusioned. Margarita Reyes became a citizen only this year; her husband is still a permanent resident. She concedes she hasn't followed Gore or Bush and doesn't know what either of them stands for. "It's my first chance to vote in November," she says. "I'm looking forward to it." Over at the Staples Center, the Democrats, allegedly the party of working people, spent the week raising more money from big corporate donors and putting on a glitzy performance for television that blissfully ignored the growing number of workers so turned off to politics they refuse to vote; or those, like Reyes, who can't tell Bush and Gore apart. In South Central, and in the neighborhoods like it across America - those places where people make less than $20,000 a year - barely two out of 10 adults vote these days. These are neighborhoods neither party has ever really cared about, except for those moments when they explode and spoil the show. South Central's alienation is in stark contrast to the fiery protests outside both the Republican and Democratic conventions. Despite many attempts by the corporate media to ignore or minimize the dissidents, or to ridicule them as a hodgepodge of

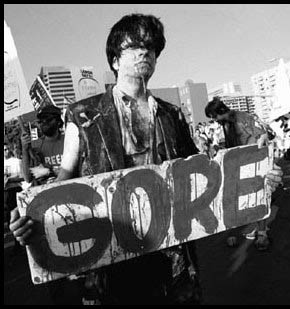

The WTO protests in Seattle last year, of course, were the watershed moment, when this international movement of peoples against the New World Order - a movement that had been developing for years - emerged from the shadows and stunned corporate CEOs and world political leaders alike. Officialdom was unprepared for the willingness of thousands to resort to civil disobedience and to disrupt the normal functioning of a city by undergoing mass arrests. It was taken aback by the cleverness and creativity, by the fervor and devotion of so many young people, who, despite being been born and bred in the ultimate individualist consumer society, chose to rebel against the immoral underpinnings of that society - things like child labor in Third World sweatshops or the destruction of the environment and animal life by global companies drunk with greed. Our country has seen vibrant social and revolutionary movements rise and fall in the past. This new generation of activists can avoid the pitfalls that crippled or doomed past efforts by learning from the mistakes of those who came before them. Already, after Seattle and the Washington IMF protests, after Philadelphia and Los Angeles, familiar danger signs have appeared. The past should teach us something. Some, enthralled by the spectacular success of Seattle, keep trying to repeat it. Some become enamored of big national showdowns, of the mere power to momentarily

Others tend to overlook or pay lip service to the big disconnect that still exists between the new movement, which is largely white and middle-class, and the millions of black, Hispanic and working-class Americans who may sympathize with some of the movement's issues, but don't yet see ways they can become a part of it. While there was more involvement by Third World youth in Los Angeles than in prior protests, I saw disturbing signs of class and racial bias even among some of the most committed protesters in Philadelphia and L.A. There was, for instance, the young activist outside the West Philadelphia puppet-making center that police raided, arresting 70 people inside who had committed no crime. A phalanx of young cops, most of them black, had been posted outside the warehouse while commanders negotiated the surrender of those inside. The raid itself was inexcusable and a clear violation of basic civil rights, but the cops on the detail were courteous and well-behaved. I listened in astonishment as the young white activist began to berate the black cops, calling them traitors to the memory of Martin Luther King, defenders of racism and oppression, and a variety of other names. As someone who has spent years chronicling the harrowing experiences of untold numbers of black and Latino cops within urban police departments in this country, I have no doubt that the average black officer encounters and often battles against far more racism than that young radical could ever hope to imagine. Not to recognize that even within the most repressive agencies and institutions of our society there are many men and women of good will battling for justice - people who could be potential allies - is an arrogance and immaturity the new movement cannot afford. In fact, the movement seems unduly obsessed with generating media attention to how police are treating it. To those of us who grew up and still live in black and brown neighborhoods in this country or immigrated from the Third World, it is hardly noteworthy that some cops can be brutal, especially when they toss you in jail. Nor is it surprising that when you challenge police authority in disruptive protests at high-profile national events, police departments will use clubs, horses, tear gas and rubber bullets. The police brutality exhibited in the various national protests during the past year should be condemned, but it hardly compares to the vicious repression and even murders suffered by civil rights and radical groups such as Southern Christian Leadership Conference, SNCC, the Black Panthers, the Republic of New Africa, the Young Lords, the Brown Berets and others in the '60s and '70s, or those that still exist in Africa, Asia and Latin America today. What is far more troubling, and what must be relentlessly exposed, is the trend toward using obscenely high bails, unconstitutional bans on assembly, pre-emptive strike arrests and conspiracy charges to prevent the growing movement from being able to organize itself or engage in future mass mobilizations, for the right of assembly is a basic right of any democracy. Despite its weaknesses, this new movement is maybe the best thing to happen to this country's radicals in a quarter century. It has already shaken up corporate America and the political establishment, and it has shown an amazing ability to get out its message directly to the American people by nurturing new independent media centers that have started to make the first cracks into the corporate stranglehold on mass media. American capitalism, however, has proven to be a resilient system. Those in power were surprised by Seattle, but they are awake now, and they will use ever more sophisticated tactics to isolate and divide the many groups and causes that made Seattle possible. The movement, on the other hand, must expand to America's heartland, or it will slowly wither and die. That means more time spent in local hometowns, educating and winning over those who now might disagree with its aims. It means airing the contradictions over tactics, methods, strategies and goals between the movement's various components through teach-ins, forums, publications and the Internet, while guarding against the intolerance, splintering and factional fights that over the years have doomed so many radical movements in American society. It means building real and equal partnerships with activists and leaders in Third World communities as well as the labor movement, not just rhetoric about fighting racism and defending workers. It means, above all, firmly grasping that the road to fundamental change in American society lies not simply in disrupting our downtowns, but in awakening, organizing and providing some vision of a better world to our South Centrals. |