|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

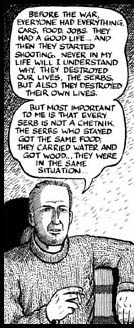

Recently I was at a backyard barbecue with my Chicago neighbors. Late at night the talk turned to books, as it often does, and I described a book that had haunted me for days. It was Safe Area Gorazde, Joe Sacco's account of life under siege in an east Bosnian outpost during the civil war. I recounted to my neighbors anecdote after anecdote from the book, trying to impress on them that they must read this book right now, that its 227 pages contained the truest, most loving and horrifying reporting yet written on the Bosnian tragedy. I told them Sacco was the Bosnian war's own Orwell, and Safe Area Gorazde was his Homage to Catalonia. After a polite silence, a neighbor interjected: "Let me get this straight: You're talking about a comic book with Chetniks in it?" Yes. Like Palestine, Sacco's previous comic book (which won an American Book Award in 1996), Safe Area Gorazde is an extended, dead-serious, comic-journalistic essay on - what else can a war correspondent write about? - man's inhumanity to man. As the Bosnian war slowly and painfully segued to a bitter, drawn-out cease-fire (optimistically called "peace" by its architects back in the Buckeye State), Sacco wormed his way through the Serb armies encircling the rural, largely Muslim Bosnian enclave of Gorazde and lived there with its citizens. With a soldier and math teacher named Edin as his guide, Sacco exhumed the stories we are already aware of - the ditches full of castrated corpses, the shreds of civilians hit by artillery, the round-the-clock rape of women in maternity wards - and drew them back to life in his chosen medium. Given Sacco's subject, many reviewers will no doubt write that Safe Area Gorazde transcends its medium. They will say it approaches the comix Olympus occupied by Art Spiegelman's Maus. These reviewers will be at least partially right: Read purely as

But Safe Area Gorazde does not transcend the comic medium. It fulfills it. For years, a few intellectuals "in the know" have rightly argued that underground comix are among the most vital of the popular arts. They have often cited Sacco as proof of this. And so, Sacco's true achievement is transcending the journalistic form. By telling his story with pictures, Sacco makes his journalism art; but by drawing his pictures with a writer's eye, Sacco makes his journalism Art. It is not what Sacco says, but what he shows that makes his story merit re-reading. Haunting the dead center of Sacco’s story is the chapter featuring a refugee from Visegrad named Rasim and his eyewitness account of Serb troops who massacred captive families on a bridge in the middle of the night, night after night. By day the soldiers rounded up more victims while drinking, playing the accordion and singing songs in their spattered uniforms. Sacco waits until almost halfway through his book before depicting this "unsubstantiated" massacre because mere atrocity - man’s inhumanity to man - is something that unfortunately no longer jars our society from its slumber. With the instinct of a novelist, Sacco knows that if we live with these people first, night and day as they soldier in their civilian way past the unspeakable horrors they have survived to the uncertainty that awaits them - then we will feel the full weight of their predicament. We have to really know these people before we can really care about them. That is all, essentially, that Sacco is asking us to do. He is not a propagandist. He simply wants us to fall in love with the people of Gorazde the same way he did: by hanging out with them. Hanging out is perhaps the most moving part of this book. It is certainly the most fun. We drink a lot of little cups of coffee with our hosts, by the candlelight or by fire, swap a lot of gossip, and help our Muslim friend Riki learn English in the way he ardently wants - by figuring out the lyrics to "Dead Flowers" by the Rolling Stones. We dance with them, laugh with them and crash on their couch every night. Then, and only then, do the Chetniks show up to torch their homes and slit their throats. In the main, that is Sacco’s triumph: to make palpable and personal a war we have heard about a thousand times before but have never let hit home. Because Sacco lived with his subjects, his book has a surprisingly quotidian focus on their day-to-day struggles. They chop wood, conjure from scratch the first pizza seen in years and build a generator to run teenage mutant movies on their VCR. They are simply fighting for the right to a normal life, and it is in this humble fight that their heroism is most apparent. A woman may be defeated, but she is not destroyed so long as she can escape to the shattered public library and read Baudelaire. A soldier cannot be hopeless while he still wonders whether or not Clyde Drexler was traded to the Houston Rockets. The picture of anticipation on a teen-ager’s face as she watches Sacco bite into a square of her banana bread, baked just for him, says more about the fragility and resiliency of her human spirit than the proverbial thousand words. Consider that proverbial value, and consider the fact that there are thousands of pictures in this book, and you begin to get an inkling of its worth. That is what I argued at the barbecue. Sitting there I felt a bit like one of the Gorazdans in Sacco’s book. I was not besieged, obviously, but there we neighbors were, huddled around the dying coals and telling stories, food in our guts, drinks in our hands. We were hanging out, just like Sacco and his friends. But the rest of our neighbors were not out there in the enclosing blackness, jeering at us from their hills. My mother had not been raped, and my father had not been shot. My neighbors were not promising to kill me. n Daniel K. Raeburn produces The Imp, a journal devoted to the comix genre. For more information on Joe Sacco, Gorazde and Safe Area Gorazde, visit the Fantagraphics Books Web site (http://www.fantagraphics.com/preview/gorazde/gorazde.html). Safe Area Gorazde is available at bookstores and comic book specialty shops nationwide, or can be ordered directly from the publisher at 1-800-657-1100.

|