|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||||

|

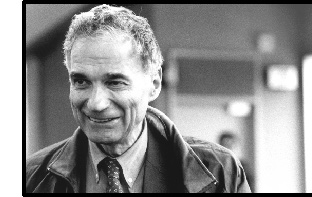

Katie Darkworth, a middle-aged, well-dressed Ohioan, dashes over to the easily recognizable, lanky figure walking through the airport in his rumpled blue suit. "Ralph Nader," she says enthusiastically, "I'm voting for you. I'm a registered Democrat, but I'm not voting for either Gore or Bush." Nader thanks her and shakes her hand. That, in itself, is unusual. Although the renowned consumer advocate now running for president as a Green Party candidate has public recognition and respect that would make any politician envious, Nader tries to avoid being identified in places like airports. He is slow to shake hands with potential supporters and proudly declines to be photographed kissing babies. Clutching his file folders and newspapers, he's more at home with serious policy talk than idle chit-chat. Though privately witty and amiable and publicly supremely self-confident, he can

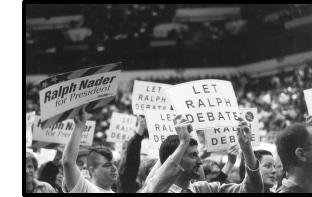

Compared to George W. Bush--all smirk, no substance--or Al Gore, with his contrived bonhomie, Ralph Nader is the anti-politician. Yet many voters this year are drawn to his straight talk and principles. After nearly 40 years as a gadfly and consumer advocate who shunned electoral politics (until a symbolic presidential bid in 1996), Nader has now concluded that citizen groups have lost their ability to win without a drastic change in American politics. By running for president, Nader hopes to build a new civic movement, a mobilization of a million citizen-activists who will not only make the Green Party an electoral force, but also revive the grassroots energy of past movements in America--from the anti-slavery abolitionists to the agrarian populists, the women's suffragists to the civil rights marchers. "This campaign is not about leaders producing followers," he told a crowd of 12,000 at the Target Center in Minneapolis on September 22. "This campaign is about leaders producing more leaders. This campaign is about thinking, not slogans and photo opportunities. It is important to have beliefs, but it is important first to have some thoughts." There is widespread popular support for much of Nader's core message--curbing corporate power, providing universal health insurance, taming globalization, public financing of campaigns, making public higher education free and strengthening environmental protection. Despite his limited funding and exclusion from the presidential debates, Nader was drawing high single digit support over the summer. After Gore's August transformation into a populist (thanks partly to Nader's threat), Nader's support dropped, though a September Harris poll gave him 6 percent of voters nationally. His relative success reflects his personal appeal, liberal discontent with Clinton and Gore, and the popularity of his program. But there are still serious doubts about his strategy even among those who admire him, agree with his policy goals and hope for a new anti-corporate movement. As Nader criss-crossed Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota on his "Non-Voter Tour," he packed auditoriums consistently with 1,000 to 2,000 people in Milwaukee, Madison, Ann Arbor, East Lansing and Flint--and he probably would have done so even without the help of celebrities like former talk show host, Phil Donahue, a longtime friend and admirer, or film and TV personality Michael Moore, who once worked for Nader. While students swelled the campus audiences, the crowds--especially in Minneapolis and Flint--also included unemployed workers and middle-aged investors, farmers and nurses, spiked-haired youth and balding lawyers. There were some alienated drop-outs as well as independents and even a few Republicans, but most were disenchanted progressive Democrats, supporters of figures like Jesse Jackson or Minnesota Sen. Paul Wellstone. The typical Nader campaign speech is a rambling free association for an hour or more through a kaleidoscopic variety of issues, moving quickly from campaign finance reform to government regulation, military contracts, corporate subsidies, income inequality, environmental degradation, civic education, corporate crime, workers rights and much more. But there is a consistent theme: "This election is all about power, the concentration of power in the hands of a few." Corporate power has corrupted politics and culture, destroyed jobs, created inequality, and undermined the rights of citizens and workers around the world, Nader says. The two-party system in the United States is a "fraud," he insists. "They are not essentially different parties, but one corporate party with two heads and different makeup." Nader inveighs against a host of corporate misdeeds, including "corporate managed dictatorial trade" (popularly known as "free trade"), "environmental violence" (as he says "pollution" should be seen), "corporate welfare as we know it" (like the public subsidies to the Texas Rangers' stadium that made Bush rich) and "brutalizing commercial culture" (that turns kids into a "generation of spectators"). He attacks "corporate crime" (that takes a far higher toll than street crime annually in death, injury and money lost from occupational disease, faulty products--like tires--and consumer rip-offs) and "corporate extremism" (in both political influence and business practices, such as redlining and usurious lending rackets). He denounces corporate agribusiness (destroying family farms and the environment), corporate control and abuse of public property (from the airwaves to the national forests), pharmaceutical companies (overcharging for drugs often developed at public expense) and military contractors (producing unneeded "gold-plated weapons systems"). The list goes on. The answer, he insists, is developing "people power" to challenge corporate power, and the "key reform" is to adopt public financing of elections to minimize corporate financial influence on politics, "the boulder on the highway to justice." While he dismisses Bush as "beyond the pale," Nader directs his most withering criticism at Clinton, Gore and Lieberman. Nader says Gore is a "political coward" suffering from "a serious character problem" who has shown an "extraordinary subservience to corporate power" and is "disgusting" in the way he panders to black church audiences while doing so little for their communities. In his eyes, Lieberman is an even more loathsome apologist for corporations. Brandishing a recent issue of Business Week, whose cover asked "Too Much Corporate Power?" ("yes," said three-fourths of those surveyed), he taunts the Democrats: "This magazine is to the left of the Democratic Party. Is the Democratic party making corporate power the cover story of the 2000 campaign?" Oddly, apart from some of the denunciatory rhetoric, much of what Nader advocates

Nader's overriding attention to corporate power, class and broad social democratic solutions has provoked some criticism that he has ignored racism and issues of gays and feminists. On his Midwest tour, especially in a Milwaukee press conference with some local African-American and Latino leaders, Nader addressed some black community issues, like police misconduct, the war on drugs, capital punishment and environmental racism. But he also insists "it is a mistake to concentrate on race and not class, or class and not race. There's a mutually reinforcing vicious circle of race and class." Typically, Nader adopts solidly progressive views on social policy but emphasizes issues of social class and power. When asked about gay rights, he says simply that he favors "full equal rights and responsibility across the board." He rarely mentions abortion rights, which he supports, "for the same reason that I don't talk about rights to public accommodation--it's a settled issue." He argues that Bush knows any attempt to overturn Roe v. Wade would doom the Republican Party because popular support for abortion rights is so strong. Most criticism from liberals and progressives, however, is directed at Nader's strategy, including his argument that the Democrats and Republicans are virtually identical on most major issues (with the exception of abortion and gun control). Assuming that one of them will win, the argument goes, Gore is better than Bush. Nader (and his advocates) offers a variety of disparate rejoinders: Voters should vote their hopes, not their fears, and follow their conscience. Or the party differences are just rhetorical and not really significant. Or Gore will win anyway, so don't worry. Or Bush isn't Genghis Khan, but a Republican moderate. Or if Bush wins, Democrats will put up a more progressive fight than they will with a conservative Democratic president. These arguments, taken together, are not completely consistent, but there is arguable plausibility to most of them. They don't, however, constitute a strategy. Nader's conviction that the Democrats are now no different from the Republicans grew out of his battles over the global economy. "I think the real turning point was NAFTA and GATT, when they put it to organized labor, which has been the cause of one Democratic election after another," he says. "And when they refused to exert any war-room mentality on behalf of public funding of public campaigns, I knew it was over." But the problem in each case was Clinton, not all of the Democrats. On NAFTA and other trade legislation, the majority of House Democrats have often opposed the president. Indeed, Nader at times praises Democrats like North Dakota's Byron Dorgan or Michigan's David Bonior and claims that House Minority Leader Richard Gephardt acknowledges that Nader's campaigning might help the Democrats gain control of the House. It often seems that Nader's real fight is with the conservative Democratic Leadership Council, but he sees no hope for winning that fight without the credible threat of liberals going somewhere else, just as conservative Democrats can threaten to go to the Republicans. At an editorial meeting of the Capital Times in Madison, Nader talks about his encounter as a Princeton undergraduate with longtime Socialist presidential candidate Norman Thomas. Hinting at his own possible strategy, Nader recounts asking Thomas his greatest accomplishment, to which Thomas replied, "having my agenda stolen by the Democratic Party." Yet Nader, who argues the Democratic party is irremediably corrupt, also talks about leading the Greens into a "death struggle" with the Democratic party to determine which will be the majority party. While riding between campaign stops in Michigan, Nader talks at length about how he

He acknowledges that if he were voting in the district of a progressive Democrat congressman, like Rep. Henry Waxman of California, he would support Waxman. Then again, if there was a Green candidate, even a weak one, he said he would vote against his longtime ally. "There's an overriding goal here, and that's to build a majority party," he says. "If you're going to build a new party, you go all the way." "I hate to use military analogies," he continues, "but this is war on the two parties. After November we're going to go after the Congress in a very detailed way, district by district. We're going to beat them in every possible way. If [Democrats are] winning 51 to 49 percent, we're going to go in and beat them with Green votes. They've got to lose people, whether they're good or bad. They've got to lose people to be put under the intense choice of changing the party or watching it dwindle." Is his goal to reform the party? "That's their option," he says. "They can dwindle us by really taking our issues and implementing them. That's the kind of competition I want. If they want to have a massive drive on corporate crime and take that issue away from us, fine." Nader is willing to sacrifice progressives like Russ Feingold in Wisconsin or Wellstone, though he also believes that the Green threat will give them bargaining power within the Democratic Party. "That's the burden they're going to have to bear for letting their party go astray," he says. "It's too bad. It isn't that we haven't given them decades, and they got worse and worse. It isn't like we have a choice. Every four years they get worse." But can the Green Party really become more than just an irritant to the Democrats? Currently the party consists of an association of state parties, some independent state parties, and a small Greens/Green Party USA that are trying to settle their ideological differences--plus the Nader campaign apparatus. Nader, however, is not a member of any Green Party and doesn't intend to join (a stance shared by Michael Moore). "I don't want to get involved in intraparty disputes," Nader says, claiming he can build the party better by attacking corporations and opponents and trying to recruit good people. "I can't stand the loss of time that's involved there. If I was a Green Party member, I'd have to take sides internally. I want to focus it externally on the adversaries." In Nader's vision, the Green Party can succeed by recruiting a million people who each contribute $100 a year and 100 hours of their time to build a "civic action" party that fights on issues in between elections, allying with labor and community groups and building storefront offices to help consumers. It sounds appealing, but there are probably fewer than a million highly active members in all existing progressive organizations. They're all flawed, Nader responds. Community groups have been "self-limiting" because they shun electoral politics, he argues, and electoral efforts like the New Party rely too much on building up from the local level without a national presence. In any case, he says, "if the level of discontent that I see around the country doesn't amount to a million people willing to make a modest commitment, then we don't have what it takes in this country. I want to put it to that test." "The only way you can fight corporate power is on all fronts," Nader says. "It's no more possible to fight just as an environmental or consumer group. You've got to grab away the media from them with a media strategy. You've got to fight them electorally. You've got to fight them with international mobilizations. You've got to fight them the way we beat the MAI [Multilateral Agreement on Investment] on the Internet. You've got to fight them with shareholder actions ... [and] with repealing Taft-Hartley. Every conceivable way, that's the only way it can be done." While Nader doubts the Democrats can be reformed, he also argues that the Greens will indirectly help progressive Democrats. "If this party is capable of internal reform," he says, "then everything we're doing is helping the dissidents and the rebels, because they'll say in year 2002 that Gephardt may lose the House because of Green Party candidates. Think of the different kind of struggle where the progressive forces in the Democratic Party going up on Capitol Hill can tell the corporate Democrats that they're going to lose voters because they have a place to go." Nader hopes that in districts where one party now rules with little contest, the Greens can enter and become the major opposition party. That's certainly a possibility in both heavily Republican suburbs or heavily Democratic inner city districts, but it is not an easy recipe for victory in either case. Though Nader has picked up endorsements from individual celebrities on the left, including Jim Hightower, Susan Sarandon, Studs Terkel, Noam Chomsky, Cornel West, Willie Nelson and Barbara Ehrenreich, few major progressive organizations have backed him (the California Nurses Association, the United Electrical Workers and a few union locals are among the exceptions). In most cases, even though they may agree with Nader, most progressive leaders remain unconvinced that the Green Party strategy holds much hope. Even some of Nader's backers think his main value may be in nudging the Democrats to adopt watered-down versions of Nader's ideas, much as Democrats stole in the past from Norman Thomas, Henry Wallace or other leftists. Some voters are simply beyond such calculations about strategy or third party prospects. They are disgusted with their choices and hope only to register a shout of protest at the polls. Others may calculate that in a lopsided race in their state, there's nothing lost in any case by casting a vote for Nader, the anti-politician who is saying what most politicians are unwilling to say. "I've always voted Democratic," says Phyllis Walker, president of a public employee union local in Minneapolis, who is still angry at Clinton about NAFTA. "I've always voted the lesser of two evils. I'm tired of voting my fears. I'm voting what I believe. Ralph Nader is the only person talking about issues important to working people. He's not a politician." With luck, more politicians will start talking like him.

|