|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

ACCRA, GHANA The cedis, the local currency, has lost half its value since January. The most common note is worth less than 30 cents. When dispensing cash, banks no longer count their bills. They weigh them. A good month's wage is the size of a brick and not much lighter. People carry their money in plastic bags because pockets (no less wallets) aren't big enough to fit their fat wads. This West African country of 19 million imports its oil, whose prices have surged this year; yet the value of its own commodities, notably cocoa and gold, have stagnated. This hurts the quality of life in Ghana. Prices are rising faster than wages. Three-quarters of Ghanaians die from preventable diseases. Foreign investment is nonexistent. "Growth is occurring, but it is unequal growth," says Yao Graham, chief of Third

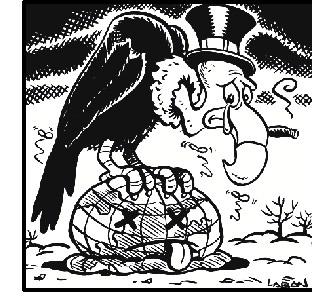

And this is in Ghana, a country celebrated by development experts as an island of tranquillity, a haven from the civil war and rampant crime that has engulfed much of sub-Saharan Africa. In the '90s, when much of Africa fell into disorder, Ghana moved toward democracy, scaled back its military, opened up its press, encouraged the spread of civic organizations and got its public finances into better order, following the stern advice of the International Monetary Fund. Even Jerry Rawlings, Ghana's president, who originally came to power in a coup, has agreed to peacefully give up office next month following national elections. Compared to its neighbors--Sierra Leone (brutal civil war), Liberia (criminal dictator and haven for diamond smugglers), Nigeria (ethnic violence and squandered oil bounty) and Ivory Coast (a recent failed military coup)--Ghana is a dream nation. What's Ghana's reward for its good behavior? Economic setbacks that make it another face of world capitalism in crisis. Globally, this crisis has spread far and wide since the East Asian currency shocks of 1997. The following year the Russian ruble collapsed, smashing the enchanting illusion that the former Soviet bloc could swiftly take advantage of freer markets, private capital and lax government regulation. Since then, the liberal ideal of private initiative and widening international trade has lost its magical allure. Even among ardent believers in the benefits of freer markets, there is a new acceptance that capitalism bestows unequal benefits. The conventional wisdom on Wall Street now reads like a populist primer: Winners are generally those countries who had a head start in terms of education and wealth, while losers often had weak economies, more poverty and poorer educational systems in the first place. Politically, the change is dramatic. The protests against the World Trade Organization in Seattle a year ago formally marked the end of the decade-long advance of neoliberal economic ideas around the globe. This fall's annual meeting of the World Bank and the IMF in Prague turned into a contest over which fat cat could show the most contrition for capitalism's shortcomings and evince the greatest sympathy for the poor. Hand-wringing by the rich shows no signs of abating. Even Bill Gates sided with the global poor recently, chiding a group of high-tech executives for insisting that innovation would somehow help the great unwashed and then asking, existentially: "I mean, do people have a clear view of what it means to live on $1 a day?" But critics of capitalism should think again before patting themselves on the back. The establishment's race to embrace critics of globalization makes a mockery of the painful re-evaluation of neoliberalism that remains to be done. Poverty pimping, on a global scale, is a beguiling sideshow. Calls for a new consensus around an "enlightened capitalism"--made by tycoon George Soros and Business Week--run smack into the reality that remedies for the market's extremes are difficult and often unpopular with capitalists themselves. Critics of capitalism rarely offer alternatives for managing the social, economic and cultural processes that fall under the rubric of "globalization." And there is a growing awareness that positive alternatives to neoliberalism are more important than the further trashing of the great beast. "We need a vision," said Andrea Durbin, a strategist at Friends of the Earth, on the eve of the Prague protests. "What do we propose instead?" The answer remains elusive. Critics are working on various responses to market failures around the world, but none are comprehensive. For instance, Durbin is helping to push a campaign to extend corporate accountability laws, prevalent in the United States, to the far-flung operations of multinationals. Others, of course, back trading rules linked to labor and environmental standards. These are worthwhile efforts, especially if they lead to heightened responsibility by multinationals for their actions in developing countries. But piecemeal reforms, as always, have limits. These limits can be grouped into two broad classes. First, those who seek to make global institutions more progressive (or "poor friendly") collide with the currents of history. These shadowy institutions, from the World Bank to the World Trade Organization, seem increasingly less influential even as protesters endow them with more power than they've had in decades. The World Bank, for all its bluster about making "poverty reduction" its top priority, has little leverage in the market. Private capital flows now dwarf public ones, so that World Bank policies count for less and less. The WTO, meanwhile, can't muster support for further trade liberalization; it can't find a way to push through the admission of China; it can't even prevent the United States and Europe from moving to the brink of a trade war. If reform of existing institutions offers limited potential, what about trying a new script? One neoliberal shibboleth is that private actors outperform public ones. But there are aspects of life, such as health care, transportation and housing, where market failures impose great social costs. The critics of capitalism need to be more radical. Maybe state ownership of production and distribution--a cornerstone of the early Cold War economic consensus--has to be resuscitated on a new basis. State-ownership fell into disrepute in the '80s in the West, with many countries dismantling, or at least sharply cutting back, direct public influence on the economy with successive waves of privatization. The questionable wisdom of this course remains unchallenged. The second type of limitation on reform stems from the nature of capitalism itself: the system is dynamic, not static. The problems of today may be overshadowed by new ones tomorrow. Indeed, the very instability of capitalism (which so animated Marx's thinking 150 years ago) is growing. No less a mainstream economic authority than Paul Krugman presented a closely reasoned paper at an elite gathering of central bankers held in August by the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank. Krugman concluded that greater economic integration was leading to more frequent crises for the system. In declaring that "persistent if low-grade anxiety" was a feature of globalized capitalism, he implied that a new crisis is incubating in the system. Everyone has their own candidate for where this crisis will erupt, though the safest bets may be somewhere in the rich world. Western Europe, with its free-falling currency and dependence on imported oil, faces fresh challenges to its competitive position and no political consensus on how to respond to threats to growth. It is one thing to bail out Mexico or Russia, but who bails out the European Union if the euro collapses? The United States, meanwhile, carries the seeds of its own undoing. Two American economists, Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff, noted at the same Fed conference that the U.S. current account deficit (the shortfall between flow of money in and out of the United States) this year reached nearly 4 percent of gross domestic product--more than double the average from 1992 to 1998. This sets the stage for a painful reversal: a drastic loss of value in the dollar, a flight of capital and an erosion of the U.S. competitive position. But before cheering this result as a matter of the United States and Western Europe getting their just rewards for so much success, even if the next crisis does hit there, it will not change the stubborn reality that the triumph of capitalism in the '90s was another of triumph for the North. On a global basis, the haves in the North (whether natives or newcomers) raced even further ahead of the have-nots of the South. And there's no sign that the gap is narrowing. Hence there is an emerging debate about what the British development specialist Robert Biel calls in his new (and unfortunately esoteric) book, The New Imperialism. The "old" imperialism, which led to the 19th-century scramble for African and Asian possessions, inspired Lenin to theorize that the West would destroy itself in a battle for colonial supremacy. He was almost right. But the rich nations learned their lessons. Whatever the "new imperialism" might be, it is not a battle for geographic position. Linked to cyberspace and knowledge industries--and leveraging unprecedented mobility of ordinary people--the new Northern imperialism sucks out what's best from the South and grafts these assets onto their winning societies, leaving the carcass of underdevelopment behind. It is this carcass that the consciences of the rich suddenly claim

to care so much about. But for how long? G. Pascal Zachary is the author of The Global Me: New Cosmopolitans and the Competitive Edge (Public Affairs) |