|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

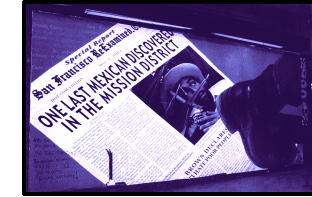

Hollow City: The Siege of San Francisco This time it wasn't a fire engine that did the job. Last summer, walking down Valencia Street in San Francisco's Mission District, I came upon the newspaper-plastered windows of Radio Valencia, a neighborhood restaurant cum art gallery and performance space. The empty storefront brought me up short; Radio Valencia was a place I could not imagine not being there. It was there when I moved to the city and the neighborhood, still there when I left almost five years later, and now it seemed that it had just been shuttered, as if it had existed until the very moment I came down the street--and then vanished. Years before, those windows, the entire storefront in fact, had been rammed through by an errant pumper-truck. No one was hurt, and a picture of the fire engine lodged three feet deep in the cafˇ's window seats made the front-page of the papers. After it reopened, the owners made a toy fire truck shrine above the bar, commemorating their little urban misadventure. It was that kind of place. This time, though, the forces of destruction were not so dramatic, but all the more final for their clean silence. And no wry memorial remained to mark the restaurant's passing, only an angry spray-painted scrawl across the glass: "Another future dot com." Welcome to San Francisco in the Age of the Internet. This is what a city of networked

It's a strange verdict on a place that has been riding the crest of the latest wave. The last six or seven years ostensibly have been good ones for San Francisco. The city weathered the economic doldrums of the early '90s, and after 1994 and the proliferation of the World Wide Web, it emerged as the capital of the Internet economy, the hip northern cousin to Silicon Valley, living large off its square relatives' venture capital trust fund. Rents and property values are up--way up. Business is booming. The city just feels richer and busier, with more cars and construction and less visible urban squalor. Formerly "marginal" neighborhoods, like the largely Latino Mission, have become ground zero for new business and residential development. But the last four or five years have seen a rising tide of gentrification panic as major office projects for high-tech and biotechnology firms went forward; builders threw up a rash of designer "live/work" spaces all around the neighborhood's industrial fringes. Besieged on all sides, the Mission's working-class, immigrant and bohemian residents and institutions have been evicted, priced out and spread to the wind. Gradually, though, these forces are regrouping; they are forming unlikely, fragile alliances to save these in-between neighborhoods, places where, as Solnit writes, "the young go to invent themselves and from which cultural innovation and insurrection arise." Hollow City is a "report from the front lines," a hastily assembled collection of essays by Solnit and photos by Susan Schwartzenberg that documents the threat to San Francisco's grassroots arts and political cultures, as well as the gathering efforts to preserve them. Solnit writes: "Whatever the Internet may be bringing the masses stranded far from civilization, the Internet economy in its capital is producing a massive cultural die-off, not a flowering. ... What is happening here eats out the heart of the city from the inside ... a siphoning off of diversity, cultural life, memory, complexity." Institutions that support political and cultural life--galleries, dance studios, nonprofits, practice spaces, co-operatives, free schools, collective spaces--are threatened by massive rent hikes. People, particularly artists, immigrants, politicos and other insufficiently upwardly mobile sorts, are being evicted or driven out. It's becoming harder to live a marginal life--by choice or necessity--in the city that has raised that dubious calling to an art form. For Solnit, San Francisco and other cities jump-started by high-tech cash are harbingers of a new urban order. Dot-com pre-fab warehouse redesigns and boho theme-park districts represent an assault on unpredictable public space. They require people whose worlds revolve around careers, virtual spaces and transportable lifestyles, not neighborhoods; they make cities that work like suburbs. In this new city, Solnit says, "Wealth has proven able to ravage cities as well as or better than poverty." Gentrification is just the latest facet of a decades-long process, one that originated as a response to "urban crisis" and suburbanization. In cities like New York or San Francisco, major financial interests--banks, foundations, insurance companies, hospitals, universities and corporations--have long tried to preserve their investments and infrastructure by cozying up to city officials, commandeering zoning procedures or federal urban renewal initiatives and generally buying up land. Massive amounts of federal dollars dropped on slum clearance projects and public housing schemes failed to eradicate poverty and reinforced racial segregation, while deepening the economic isolation of already poor neighborhoods. In the '60s, '70s and '80s, while the ghettos burned, welfare rolls thickened, and the economy surged and fell and surged again, those interests that wouldn't or couldn't decamp to the suburbs consolidated San Francisco's Financial District and vast parts of Manhattan's southern tip and middle reaches into white-collar office precincts. Vibrant blue-collar cities--that once had only small extremes of wealth and poverty--became increasingly divided between riches and lack. Gentrification simply represents the city's rescue on these terms. It should be no surprise then that these bifurcated metropolises of the postwar era--one part ghetto, one part office district with a shrinking working class and fleeing middle class in-between--are being transformed into upmarket monocultures. In the late '60s and '70s, a small portion of the middle classes began returning to the city to live as well as work--even as the politicians and newsmen announced the onset of an "urban crisis." Real estate speculation in residential and commercial property returned to the neighborhoods of urban America in halting increments over the past 30 years, in a mounting series of booms felt most acutely in the profits of owners, the rents of tenants, and the prices all of us pay for everything from a meal to a lost sense of civic culture. Gentrification represents the triumph of those forces that learned to preserve themselves in times of urban poverty. Not surprisingly, that poverty has not been banished. It's only harder to see and more isolated as it seeps out into the suburbs, entrenches in the housing projects that have yet to meet the wrecking ball, or transforms into the spiritual poverty of a city leveled and made simple as it gorges on the heady sureties of newfound wealth. Gentrification scares are endemic to the culture of neighborhoods like the Mission. Aware bohemians are self-conscious about their role in changing the barrio, and many Latino residents, while they welcome the business, are unmistakably wary of white newcomers. When I arrived in San Francisco--before the Web in a time of scarce jobs and somewhat affordable rents--a friend was writing the "oral ourstory" of Studio 4, a residential collective and illegal performance space at 18th and York. Part of this process was a sort of ritual self-examination--one that is repeated again and again by successive waves of white artists and politicos moving into lower-income communities of color. Studio 4 had been there for almost nine years, but could never escape the inevitable truth that the neighborhood was changing because of their presence. My friend and his fellow collective members understood that they were "pawns in a big real estate game," and that places like Studio 4 or Radio Valencia (probably a step further on the gentrification chain) block-bust the neighborhood and make it safe for the real money. Studio 4 considered a number of strategies to drive out the yuppie incursion: graffiti binges, fires in trash cans, vandalizing newcomers' cars, and leaving trash, old furniture and excrement in the streets. They even proposed staging fake drive-by shootings and drug deals on their block. In the end, they realized that street theater and trashing an already taxed block was no substitute for the actual work of organizing, for reaching out to their Latino neighbors--and maybe even the drug dealers and prostitutes--to try to find some common ground. Studio 4 disbanded in the early '90s, and that northeastern corner of the Mission has been hit hard in the recent dot-com boom. Still, Studio 4's anti-gentrification efforts have their legacies too. Solnit and Schwartzenberg document--and criticize--pranksters like the Mission Yuppie Eradication Project, whose street posters urge the trashing of SUVs to "drive these cigar bar clowns back to Orinda and Walnut Creek where they belong." The Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition, a confederation of artists, housing advocates and Latino activists, have staged marches, protests and even a brief takeover of a dot-com office in a Mission Street building that once housed nonprofits. A ballot initiative to limit or end office growth in certain hard-hit neighborhoods did not pass in November, but a slate of progressive city supervisors did. Now that they have a majority, plans are afoot to legislate growth controls over pro-development Mayor Willie Brown's veto. For her part, Solnit is reluctant to "blame" artists for gentrification. "Gentrification is like air pollution," she writes. "A lot of unlinked individuals make contributions whose effect is only cumulatively disastrous. One can blame artists and drivers for those cumulative effects, but such effects are not their intention." Still, she reveals that in 1988 a group of San Francisco artists "managed to get a measure passed that allowed them to build or convert in regions zoned for industry, to circumvent building codes, and to avoid affordable housing stipulations and a significant portion of school taxes." Ignoring the warnings of housing advocates, these artists organized to opt out of the social contract--and it came back to haunt them. The flood of overpriced live/work "lawyer lofts" poured through this very loophole. Of course, this is only one part of the story. Surely artists and their ilk are not entirely to blame--little is said here about landlords, for instance. But maybe Solnit soft-pedals the bohemian factor in gentrification for, in part, deep and abiding emotional reasons. She believes in San Francisco. For her and other longtime San Franciscans the place is an ideal. It's fragile and flawed perhaps, but still a "visionary city." I'll admit to being somewhat impatient with such self-struck Bay Area righteousness.

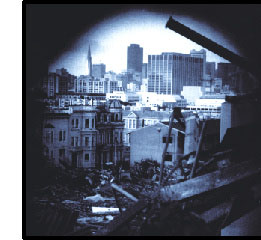

No doubt that when the cultural history of the '90s is written and the indelible ties between the "alt-culture" boom and the dot-com boom are made plain, San Francisco will provide the setting. Too often it's a city on display, fascinated with its own indulgence in the accoutrements of disaffection, or increasingly, placeless cosmopolitan sophistication. But this is the trick with San Francisco. From another view, Solnit is right, and with a little digging and time these surfaces reveal depths. The legacies of the cultural, social and political movements that have left their mark on San Francisco remain today, and their spheres of influence have grown evermore intermingled. The city's cultural foundations are set several generations deep in the shifting sands, bedrock schist and landfill beneath its narrow peninsula. From City Lights Books to a number of feminist and lesbian community spaces to punk collectives to hip-hop activist groups to the Mission's Latino mural movement, it would be hard to entirely separate out white middle-class bohemian newcomers from people of color. In the terms Solnit favors, there is an interconnected "ecosystem" of cultural life; real-estate speculation is like an invading algae choking out the diversity and variety with singular fervor. Solnit is also careful to point out that, for better or worse, art scene hipsters and IPO babies can easily inhabit one and the same body. In San Francisco, I was both bike messenger and hypertext millhand at one time or another; it seems simplistic to single out particular "types" of people for blame or admiration. Still, preserving the threatened city will take sacrifice on the part of some artists and upwardly mobile sorts who might otherwise prosper from the city's economic success. It will take the kind of political organization that requires people to recognize differences but forge solidarity. Solnit and Schwartzenberg's idealism is not the only thing that makes this political alliance a hopeful possibility. Imaginations that can evoke place with such integrity must surely have some success in shaping those places as well. Schwartzenberg's photo collections do their job here, both as illustrations of Solnit's piece and as critical reflections on the ambiguous nature of the loss of places one values--or never knew mattered until they had been transformed. She also brings in the work of photographers who produced "San Francisco in Chains"--a project documenting the Starbucks deluge (there are now about 60 around the city) and the businesses they displaced. Hollow City was written quickly, and the prose often suffers in comparison to Savage Dreams, Solnit's crucial and moving essay on the confluence of politics and landscape in Yosemite and the Nevada Test Site. Still, Solnit remains one of the foremost writers on place working today. "Cities," she writes, "are the infrastructure of shared experience." They thrive because in them people "share public goods--public parks, libraries, streets, cafes, plazas, schools, transit--and in the course of sharing them, become part of a community, become citizens." And in time place can exert a subtle yet forceful pull in the mind and heart. "For those who spend years in a place," Solnit says, "their own autobiography becomes embedded in it so that the place becomes a text they can read to remember themselves. ... When culture and memory are evicted from a city, its places, its locations and its products become mute commodities that can be purchased but not dreamed." The bloom is off the Web rose now, and some hope a recession, whatever its larger regrettable effects, might turn the tide. Anecdotal evidence suggests that commercial starts have fallen off in the last few months, but evictions and rent hikes continue. High-tech is in San Francisco to stay; now it's a matter of whether the city can find a political way to reconcile growth, wealth and equality. Some feel that growth controls will have ripple effects in the housing market, further discouraging the construction of low-income housing. Others respond that these limits will spur small-business job growth and allow rents to settle. Either way, in the twilight of the "long boom," a certain ineffable sadness hovers in the streets of San Francisco. Perhaps these are merely the weightless cavils of nostalgia and escaping youth, the refusal to accept and move with change, but that hardly depletes the force with which Solnit and Schwartzenberg convey the costs of loss. Whatever the future holds, the legacy of loss will remain. It is unavoidable, because it is written in stone, steel and glass in the cityscape. Last summer, walking through some familiar reaches of South of Market near downtown, I lost my bearings. These were streets I had traversed countless times on my bike delivering packages in years past, but it seemed now as if only a shadow or hint of that place remained. Empty lots had been filled, buildings I used to go in and out of daily were gone and replaced with new glass towers. Telling details remained, but the context, the background, had morphed. Spaces where I intuitively expected to see sky were filled with glass and steel; old masonry street fronts were now open, antiseptic plazas. I stopped at a corner before a vacant lot jumbled with demolition

equipment, trying to remember what had been there before. Towering

above the lot was an immense white banner, one of those massive,

austere Apple Macintosh ads commanding us to "Think Different."

It rippled down the entire flank of an old, gutted five- or six-story

building, whose facade had been pulled away to expose the orderly,

crude masonry grid of its floors and rooms to the street below.

Here, then, was the new economy sweeping away the useless infrastructure

of the old, the champions' banner erected already over the ruins

of an outmoded world. But the banner, like so much in this city

taken by Solnit's quiet "siege," had been unable to hold fast in

the storm of progress. One corner had come unmoored from its pins.

Loosed and noisy, it fluttered and flapped remorselessly among the

wrecking cranes in a darkening wind that blew the afternoon fog

off the ocean, over Twin Peaks and across the last of the day's

sun.

|