|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

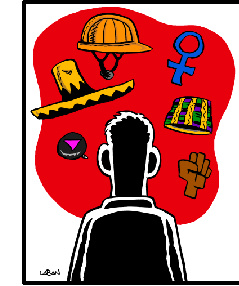

In recent years there has been a mounting attack on "identity politics," political groupings that push agendas based on race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation. Such politics, it has been argued, hardens boundaries between oppressed groups and, further, prevents them from mobilizing collectively around the more important issues of class division and economic inequity. In his 1995 book, The Twilight of Common Dreams, Todd Gitlin characterized "identity politics" as "groups overly concerned with protecting and purifying what they imagine to be their identities." Not only are these groups self-deluded, but, according to Gitlin, "Identity politics is an American tragedy ... a very bad turn, a detour into quicksand." Since 1995, Gitlin's thesis has found wide currency among straight white men on the

The critics of identity politics (including some gay critics, like Andrew Sullivan) insist that multiculturalists must "stretch beyond" their cultures and identities, beyond a shaky coalition of outgroups, beyond the demands that have, according to Michael Tomasky, "nothing to do with a larger concern for our common humanity and everything to do with a narrow concern for fragmented and supposedly oppositional cultures." Others who have inveighed against identity politics usually do so in comparably patronizing terms. Ralph Nader told us, for example, that "gonadal politics" are a trivializing distraction from the genuinely important agenda of economic issues. Those on the left who inveigh against identity politics assume that "class" is the transcendent category, and issues relating to gender, race and sexuality are marginalized as comparatively insignificant. Among the many confusions in attempting to establish a hierarchy of what is the "most" or "least" important social issue is a bottom-line unawareness of how these struggles intersect. The labor movement itself can quite reasonably be described as historically based on identity politics: For a long period it exclusively defended "its own." Class solidarity was reduced to protecting union members against the great unwashed, unorganized mass of female and nonwhite workers. Indeed, racism, sexism and homophobia in the workplace inescapably affect how and whether workers will see their grievances as ones held in common. Until the CIO came along in the '30s, black workers were essentially barred from union membership, and are still not fully welcome in some industries like construction. Many working-class whites have long since chosen to identify with their skin color rather than with "alien others" (especially blacks) who share their class oppression; it has been more important to declare their superiority to blacks--and their primary bond with fellow whites of all classes--than to collaborate with "inferiors" in a protest movement based on class. In other words, long before identity politics purportedly pushed the white working class to the right, its own conservative cultural views had long since solidly planted it there. "Class," in other words, is inherently a cultural issue; solidarity based on economic issues can never come about until divisions based on gender, race and sexuality are recognized (even if not resolved) as central to achieving such a goal. As Amber Hollibaugh has argued in her recent book, My Dangerous Desires: "I don't think the union movement can survive if people don't see it as part of their culture. ... Issues that are specific to their individual social experiences have to emerge ... but gay people are working-class people ... they need to be able to bring their queer, working-class selves out to the union. ... Does the union movement want its children or not? That's the real question." To which I would add a second "real question": Is the gay movement ever going to be willing to take on the class dimensions of its own struggle? To date, it has not. And that is why most national gay organizations push for agendas (gay marriage, gays in the military) that do not resonate for, say, working-class dykes concerned about issues relating to shrinking real income or dead-end jobs or HIV or substance abuse or domestic violence. If we in the gay movement need to recognize class-based issues more, the critics of identity politics need to understand that issues relating to gender and sexuality are not trivial, but central to people's lives. Instead of such recognition, we are subject to lectures about the relative unimportance of our issues, chastising us for our "narrow" concern with our "supposedly" oppositional cultures. Our critics continually refer to identity politics as a "distraction." They refer to "faux-radical multiculturalism" and its "superficially transgressive ideas." But declaring certain ideas superficial does not make them so--especially since it is far from clear that these critics have remotely understood them. They need to draw their chairs in closer and listen harder to the intricate conversations taking place on the multicultural left. The radical redefinitions of gender and sexuality that are under discussion (and contention) in feminist and queer circles contain a potentially transformative challenge to what has been called "regimes of the normal." The critics of identity politics give no sign that they have actually read, let alone absorbed, the work of queer theorists like Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Jeffrey Weeks, Michael Warner, Wayne Koestenbaum or Judith Butler--to name only a few of the more prominent. A large body of work now exists that, taken together, presents a startling set of postulates about such matters of universal importance as the historicity and fluidity of sexual desire, the performative nature of gender, and the complex multiplicity of attractions, fantasies, impulses and narratives that lie within us all. These are not small, narrow, superficial matters of concern only to the self-absorbed few--ignorance alone allows them to be so characterized. Were the anti-identity politics crowd to open its ears and refuse to settle for Reader's Digest versions of feminist and gay analysis, it would have to come to grips with any number of discomforting notions. To understand how and why sexual and gender identities get socially constructed is, in fact, to open up a new way of talking about politics, of talking about how relations of power get established, about the role of the state in reinforcing and policing that set of relations in the name of maintaining the stakes of the already privileged. Try to imagine the consequences, for example, of reconsidering, as feminist and queer theorists have been asking us to do, traditional definitions of gender. Is it fair to men (we know it isn't fair to anyone else) to be viewed as inflexible, driven engines of action, accumulation and domination? A freer definition of the male self, the heightened ability of men to embrace the varied impulses within, could loosen their iron drive for control, their over-representation in positions of power, their unmodulated resort to violence as the preferred means for resolving conflict. These are emancipatory possibilities--for everyone. They could lead us back to that unfinished dialogue from the '60s about the nature of "human nature," about the need for personal transformation to precede or accompany any lasting social transformation. This is hardly an ersatz sideshow. It is instead a matter of the non-feminist, non-queer left not bothering to listen, not taking seriously the foundational work being done on gender and sexuality. If it were listening, it would find potent tools at hand for informing the struggle against entrenched class (and race and gender) hierarchies of privilege and power about which they care so much. The ideas being generated on the multicultural left are not "supposedly" oppositional; they are fundamentally so. They have everything to do with the "larger concern for our common humanity" that our critics loudly insist is absent from identity politics. Perhaps henceforth, when we talk about "re-envisioning the left," we need to put high on the agenda (it is now nowhere in sight) the patronizing inability or unwillingness of many on the left to take seriously the far-reaching work being done in feminist and queer circles. Moreover, a long-standing debate has been going on among multiculturalists themselves about the inadequacy, incompleteness or possible transience of identity labels like "black" or "gay" or "Latino." Many minority intellectuals are troubled about the inability of overarching categories or labels to represent accurately the complexities and sometimes overlapping identities of individual lives. We are also uncomfortable referring to "communities" as if they were homogenous units rather than the hothouses of contradiction they actually are. We're concerned, too, about the inadequacy of efforts to create bridges between marginalized people and then extensions outward to broader constituencies. Yet we hold on to a group identity, despite its insufficiencies, because for most non-mainstream people it's the closest we have ever gotten to having a political home--and voice. Yes, identity politics reduces and simplifies. Yes, it is a kind of prison. But it is also, paradoxically, a haven. It is at once confining and empowering. And in the absence of alternative havens, group identity will for many of us continue to be the appropriate site of resistance and the main source of comfort. The anti-multiculturalists' high-flown, hectoring rhetoric about

the need to transcend these allegiances, to become "universal human

beings with universal rights," rings hollow and hypocritical. It

is difficult to march into the sunset as a "civic community" with

a "common culture" when the legitimacy of our differentness as minorities

has not yet been more than superficially acknowledged--let alone

safeguarded. You cannot link arms under a universalist banner when

you can't find your own name on it. A minority identity may be contingent

or incomplete, but that does not make it fabricated or needless.

And cultural unity cannot be purchased at the cost of cultural erasure.

Martin Duberman teaches history at CUNY. This article was adapted from an essay in his most recent book, Left Out (Basic Books). His play on the life of Emma Goldman will be produced this coming season at Rattlestick Theater in New York. He is completing a novel on the Haymarket Affair.

|