|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||||||

|

In the lush marsh and channels that weave across Bolivia's far east, the river boat stirs through dense copper-colored waters beneath the blaze of an afternoon sun. Small green parrots shriek across the sky and, as twilight approaches, a mother capybara leads her young through grass along the shore. Troops of howler monkeys crowd onto the limbs of tall trees. And the black eyes and double-barreled snouts of caiman wait motionless on the water's surface. A day's journey from the dusty Bolivian port town of Quijarro on the border with Brazil, our crew of 18, on a trip financed by the World Wildlife Fund, is exploring the waterways of the Pantanal, one of nature's wildest and most remote places--one we hope stays that way. The world's largest freshwater swamp and the best place to view wildlife in South America, the Pantanal is facing a series of environmental threats that are challenging the economic and human resources of Bolivia, the continent's poorest nation. Illegal trafficking in animal species--the world's third-largest contraband industry after drugs and weapons--has caused considerable damage to the biodiversity of the area, which is shared by Brazil (75 percent), Bolivia (20 percent) and Paraguay (5 percent). In this unique ecological zone, home to anaconda, tapir, macaw, piranha, giant anteater

The fate of other species in the Pantanal, like the river otter, hunted for its costly pelt, and the borochi--a large fox-like animal sought for its medicinally valuable bones--are still uncertain. And the decline of the gama, a horned savanna deer, has biologists baffled and alarmed. "Gama used to show up in groups of five and six," says Marcel Caballero, a Bolivian wildlife biologist. "Now they are rarely seen more than one at a time. They might be too sensitive to the presence of humans. Once these animals are scared, they stop reproducing, just like in the zoo." In the 1860s, Bolivia's senile and dictatorial President Mariano Melgarejo cut a deal with Brazil: In exchange for "a magnificent horse," he laid his hand on the map and, covering a swath of territory in Bolivia's far east, declared it the property of Brazil. The site of gold discovery and colonization in the early 18th century, the Pantanal was mostly left alone well into the 20th century, when unrestricted cattle grazing and an extensive road network started to eat away the wild region, particularly on the Brazilian side. By 1998, more than 23 million head of cattle roamed the swamp. Less developed than Brazil--which preserves just 10 percent of its Pantanal as the Matogrossense National Park--Bolivia still has reason to be concerned about its side of the swamp, which at 11,600 square miles is approximately the size of Holland. Now that Brazil has cracked down on illegal hunting, fishing, logging and mining in the Pantanal--punishable by up to four years in prison--some Bolivians are worried about an increase in poachers crossing the border to continue their assault on species and resources. Since 1990, Bolivia has had a general ban on hunting and trade in wildlife, though the law has been poorly enforced. In addition, runoff from chemical fertilizers and pesticides for soybean and other cash crops grown on nearby ranches endangers the region's ecological health. Controlled burns by farmers expanding cattle-grazing areas often rage out of control, devastating large areas of plant- and animal-rich grassland. And mercury still used for gold mining in the swamp's interior has killed scores of fish--of which the Pantanal contains some 260 species. On a more organized scale of human meddling, Shell, Enron and Bolivian

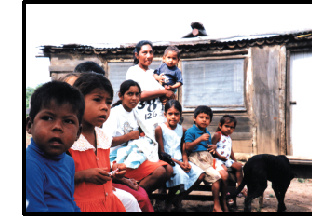

On this journey up the Paraguay River and its tributaries, our crew is a mix of indigenous leaders, park officials, naval officers and a cook who fries up the dozens of piranha we fish out and eat nightly. I am the only non-Bolivian aboard the two-deck military boat, and the events of our journey are varied: Several times a day, we speed off in a johnboat to see rare clusters of the giant pictoria plant, or pull up on land and walk knee-deep through marsh and mud to isolated ranches where we talk with farmers in Portanol--a mix of Portuguese and Spanish--about their living and working conditions. The excursion's goal is to explore and confirm national boundaries within the swamp, and to meet with indigenous communities living there, explaining to them the status of the San Matias Protected Area. Created in 1997, San Matias is the most recent of Bolivia's 20 protected areas, which comprise nearly one-sixth of national territory. An estimated 6,000 people--half under the age of 15--live among the 17 indigenous communities in the region, growing yucca and rice, raising chickens and pigs, and gathering fruit that falls from the trees. For some the native language and culture is Guarani, while others are Chiquitano, and although they outfit themselves in basic western apparel of T-shirts and shorts, their lifestyle of agriculture, fishing and animal husbandry appears largely unchanged by the decades. The Bolivian government employs just eight workers--a director, a protection chief and six park guards--to supervise its portion of the Pantanal. Though the staff of San Matias receives financial and technical help from the World Wildlife Fund, its members admit that present resources are inadequate to oversee the area's preservation. Lacking in personnel, aircraft, vehicles and communication with the interior, park guards say they rely more on the cooperation of indigenous communities than on government funds to protect their wilderness. "The people here are easy to speak to about conservation," says park director Jorge Landivar. "They are conscious that they can use nature responsibly." But seated on wood benches in a dirt yard of Puerto Gonzalo, an indigenous community some 24 hours by boat from the Brazilian city of Corumba, site of the nearest hospital, we see the people whom progress has left behind. The town has neither a doctor nor medical goods, and its one-room schoolhouse has sat empty since the last teacher left years ago. A poor farmer and his family offer us cups of water. The man has a pink pigmentation on his hands, neck and lips and the rest of him is a leathery brown. He says his only vices are mate and cigarettes, and he's missing four top front teeth. With canvas shoes torn at the seams and his callused toes protruding from them, he talks about how little water there is in the laguna at this time of year. There is an awkward, uncertain silence at the meeting, where men sit on one side of a

The Bolivian government and the World Wildlife Fund hope to attract "ecotourists" to the area, which could allow Puerto Gonzalo and other remote indigenous communities to continue their farming lifestyle while helping enforce preservation in the region. Bolivia generated $179 million in tourism in 1999, and the government estimates that its current mark of 500,000 visitors a year will reach a million by 2004, providing 150,000 new jobs. Riding the surge in tourism into the Pantanal might be the compromise the swamp's communities make to retain their old ways of life. The lure of cash through ecotourism as well as a drop in the price for cattle has already prompted many Brazilian farmers to convert their ranches into fazenda-lodges, accommodations that serve visitors on excursions into the swamp's interior. In the Pantanal's rugged and mountainous tropical landscape, both high- and low-end tourism are on the rise. River trips in the region have even been popularized by writers such as John Grisham, who structured his novel The Testament around an adventure that takes place in the Pantanal. But Bolivia faces the task of developing an ecotourism strategy from scratch, one that competes with Brazil while having a minimal impact on the environment. According to Ascensio Ares, vice president of a local indigenous association, the Bolivian communities must adopt a higher standard of living before they can host tourists in their backyard. "If we don't strengthen this type of development," he says, "the problems in the area will only continue." Its history mired in poverty and corruption, Bolivia is still struggling to develop a basic infrastructure of roads and industry, the lack of which has helped keep vast portions of its jungle intact, more so than its tropical neighbors. But to succeed with ecotourism, some fundamental progress will be necessary. "You can't have tourism if there is no road," explains Hernan Banegas, an architect from Puerto Suarez, a town that borders the Pantanal and is reachable only via the ancient railway line known as the "death train," which rattles 400 miles east from Santa Cruz. A successful transition to ecotourism in Bolivia already has one clear example:

Still reeling from the shock of privatization enacted by neoliberal leadership in the mid-'80s and continued by ineffectual administrations through the '90s, Bolivia continues to underfund its environment, while many of the country's top officials guard close ties to major logging, mining and energy interests. Maybe less often mentioned in poor nations like Bolivia is the latent public consciousness of the need to preserve its wild, unspoiled places. "In the past no one spoke of conservation, of ecology," Banegas says. "They cut trees, they killed animals--thousands upon thousands of alligators just to sell the skin and eat the tail. By necessity and ignorance we exploited nature. Only 10 years ago, we didn't know the word medioambiente [environment]. Now they tell us our Pantanal is the biggest lung of the planet." It might be the indigenous communities themselves who have the

most to do with guarding the region's long-term health. According

to Landivar, generations have kept the vast swampland in its relatively

unaltered form, and the native people still living there understand

their responsibility to live within it in that same way. "If the

Bolivian Pantanal is less damaged by man, it's because the region's

inhabitants took only what they needed for centuries," he says.

"There is no other place like it in the world." Michael Levitin is former editor of the Bolivian Times, an English-language newspaper published in La Paz.

|