Pesticide Industry Joins New York’s Pollinator Task Force—Bad News for Bees

Tracy Frisch

As in other parts of North America, beekeepers in New York have been experiencing unsustainable losses of honeybee colonies. According to the Bee Informed Partnership survey, in 2014 and 2015, annual colony losses in the state reached 54 percent. And though losses were lower in preceding years, they consistently exceeded the economic threshold of 15 percent loss. At great expense, New York beekeepers have been able to recoup their winter and summer losses, but for declining native bee species the prospects are less rosy. For example, the rusty-patched bumblebee (Bombus affinis), once common in New York and the Northeast, is now a candidate for the endangered species act.

A growing worldwide body of scientific evidence implicates neonicotinoids as a major contributor to the decline of honeybee and wild bee populations. As reported in the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Worldwide Integrated Assessment of the Impacts of Systemic Pesticides on Biodiversity and Ecosystems, 2015, this is due to a combination of neonicotinoid’s acute toxicity, sub-lethal, intergenerational, neurotoxic and immune system effects; their systemic behavior in plants and their persistence in soil and water. This relatively new family of insecticides is now believed to be the most commonly used global pesticide.

Unlike Europe and Ontario, Canada, the United States has not acted to restrict the use of neonicotinoids. However, the federal government has specifically urged states to create pollinator protection plans. Some states are working on such plans and a few have been implemented. But on August 6, at the first meeting of the New York State’s Pollinator Task Force, commercial beekeeper Jim Doan was flabbergasted to learn that state officials had appointed two representatives of the national pesticide industry to the 12-member panel. “It’s very difficult for a beekeeper to think he can get a fair shake,” says Doan.

Consequently, I decided to see for myself and attended the Task Force meetings on September 11 and October 1, and listened to the recording of the August 6 meeting.

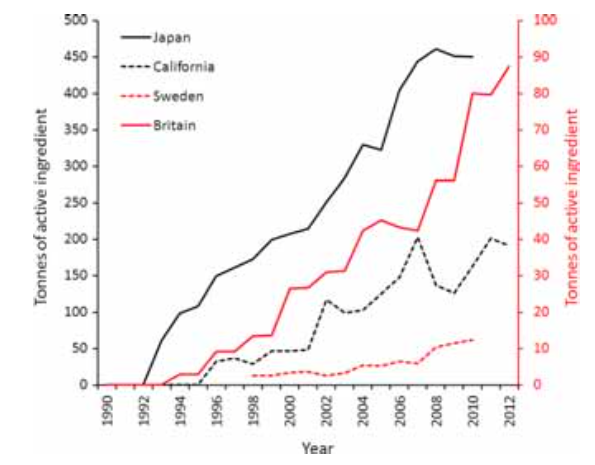

Measured here in tons of active ingredient per year, the amount of neonicotinoid insecticides shipped and used internationally has been surging since the early 1990s. (Graph: The Task Force on Systemic Pesticides)

The New York State Pollinator Task Force

The New York state Task Force was set in motion by Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D), who said in an April 23 announcement, “Pollinators are crucial to the health of New York’s environment, as well as the strength of our agricultural economy.” He added, “By developing a statewide action plan, we are expanding our efforts to protect these species and our unparalleled natural resources, and making an important step forward in our commitment to New York’s ecological and economic future.”

Cuomo directed the state departments of agriculture and markets (NYSDAM) and environmental conservation (NYSDEC) to develop a state pollinator protection plan with the involvement of stakeholders and research institutions.

By July, stakeholders were receiving invitations to serve on the state Task Force, which was comprised of 12 “advisors” from the private and NGO sectors with officials from NYSDAM and NYSDEC serving as co-chairs. In addition, Cornell Integrated Pest Management program director Jennifer Grant sat with Task Force members and played an advisory role, though not as a member.

Task force membership

In terms of its personnel, three groups represent pesticide interests on the Task Force: CropLife America and Responsible Industry for a Sound Environment (RISE) are the pesticide industry’s agricultural and non-agricultural trade groups respectively. Both are headquartered at the same Washington D.C. office. The NYS Agribusiness Association is the third agrochemical group. Dan Digiacomandrea, a technical sales specialist at Bayer CropScience, one of two makers of neonicotinoids, attended one meeting as that group’s alternate.

Agriculture also got three seats, with appointees from the state farm bureau, state vegetable growers association and the fruit sector. The state vegetable growers consistently sent an alternate, Rick Zimmerman. His resume includes many years as a Farm Bureau lobbyist followed by a career as NYSDAM deputy commissioner. Today he heads up the Northeast Agribusiness and Feed Alliance. The state turf and landscape association has a seat, too.

Three NGOs were appointed to the Task Force: The Nature Conservancy, Audubon New York and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). Member Erin Crotty, who is executive director at Audubon New York, previously served as DEC commissioner under Republican Governor Pataki. NRDC, which has sued EPA on neonicotinoids, was represented by one of two alternating attorneys at each meeting. Like the aforementioned industry representatives, no one from these organizations appeared to have any specific expertise on pollinators. The representatives rom the Nature Conservancy and Audubon New York proposed ways to increase pollinator habitat but did not indicate concerns about pesticides.

Beekeepers were apportioned two seats. With 12 hives, hobby beekeeper Stephen Wilson has chaired the Apiary Industry Advisory Committee for over 15 years. The other representative was Empire State Honey Producers Association president Mark Berninghausen, a small commercial migratory beekeeper from St. Lawrence County. This group has about 100 members out of the 3,000 or 4,000 beekeepers in the state.

The state has also been accepting public comments (though this was apparently not publicized and no deadline has been announced). These comments must be submitted to the governor’s office, not to the Task Force directly (initially NYSDAM was accepting them). As of this writing, these comments have not been shared with task force members.

Given the make-up of New York’s Pollinator Task Force — one-quarter pesticide industry, one-third agriculture and turf care industries — and the political allegiances of the two convening agencies, the complex issue of pesticides was therefore always likely to be handled with kid gloves.

The timeline and the content

At the kickoff meeting task force advisors had a chance to lay out their positions on what the state should do to protect bees. The second meeting focused on research needs and the third dealt with habitat enhancement and best management practices (BMPs).

Presentations took up much of the second and third meetings. For example, a series of managers from six state agencies described their land management practices and initiatives to provide habitat in respect to bees.

A highpoint was the talk by Cornell’s new honeybee extension entomologist, Emma Mullen. A Canadian who just moved to the United States, Mullen had been part of the team of scientists that worked on Ontario’s Pollinator Health Protection Plan. Particularly illuminating was her explanation of the province’s new program to decrease the corn and soybean acreage planted with neonicotinoid-treated seeds 80 percent by 2017. She also outlined current Cornell research on bees.

NYSDAM commissioner Richard Ball, a vegetable grower, chaired the meetings and NYSDEC deputy commissioner Eugene Leff played a supporting role. Leff, whose resume includes pesticide regulation, previously presided over another stakeholder task force charged with dealing with an equally polarizing issue: preventing pesticide pollution of Long Island’s groundwater. As with the pollinator task force, pesticide and agricultural interests were well represented on Long Island. (The 126-page strategy document that came out of that task force’s work indicates that these interest groups succeeded in delaying any restrictions on suspect pesticides.)

To frame the initial Pollinator Task Force discussion, Commissioner Ball reiterated what has come to seem like the official national dogma on bee decline — there is no single cause and we must consider multiple areas of concern. While the list of pollinator threats varies, the USDA, EPA and institutions such as Cornell University cite factors such as habitat loss, pests and pathogens, pesticides, genetics and/or climate change when they state that view.

Indeed, the most notable feature of the meetings was the overall reluctance to delve into the problem of pesticides except in so far as they induce immediate bee kills. Only two members of the 12-member task force (beekeeper Stephen Wilson and a Natural Resources Defense Council attorney) urged any limitations on the use of neonicotinoids.

Meetings without minutes or structure

A number of additional aspects of these meetings support the idea that the Task Force exists primarily for appearance’s sake. First, no one appeared to be taking official notes and no minutes were made available, despite advisor Stephen Wilson’s request for minutes at the second meeting. (Recordings are posted on NYSDAM’s website.) Second, no one wrote down ideas on a whiteboard or easel to capture them as they came up. Third, Task Force discussions were freewheeling, unstructured and all over the map.

The state’s short timeline, which called for the state to circulate the NYS Pollinator Protection Action Plan Recommendations to task force members on October 19 followed by a 7-day comment period, also challenges the notion of a deliberative process informed by science. The whole process, from the first of three Task Force meetings to the submission of priority recommendations to the governor, is scheduled to take only three months. (As of October 28, a beekeeper on the Task Force reported that he hadn’t received anything from the state yet.)

Yet the meeting agendas presume that in an hour or two of meetings these advisors will contribute content to the pollinator plan, generate a meaningful research agenda and cobble together BMPs to protect bees.

The idea that all this can happen fails to pass the laugh test. Thus, in the final portion of the third meeting, Task Force advisors were asked to consider a series of BMPs listed on a handout prepared in advance (presumably by NYSDAM or DEC) but not distributed until the actual meeting. Task Force members had not gotten through the first item on the list when time ran out.

Discussion of specific BMPs was overshadowed by the contentious issue of whether beekeepers should be required to register all honeybee hives with the state and disclose their locations. BMPs listed on the handout pertained to such things as beekeepers’ care for their colonies and control of mites and other parasites/diseases, landowners and state agencies enhancing pollinator habitat and forage, the correct and judicious use of pesticides and of Integrated Pest Management, and the roles of beekeepers, landowners and pesticide applicators in protecting honeybees from pesticides.

Perhaps there was no real need to carefully craft a plan because the conclusions appeared to have been pre-ordained. In his closing comments at the third meeting, DEC deputy commissioner Leff referred back to the governor’s blueprint for the state pollinator plan. In particular, Leff highlighted the BMPs designed to reduce pesticide exposure to managed pollinators through better communication among beekeepers and farmers. Leff stressed the need for landowners and pesticide applicators to know where hives are located and how to contact beekeepers before they spray.

Of course, Beekeepers would have to be ready to move their hives. Some beekeepers fear that New York’s plan will follow North Dakota’s template — transferring the burden of protecting honeybee colonies from pesticides onto the beekeepers. This is at odds with the historical assignment of such responsibility to pesticide applicators. In fact, pesticide labels carry legal weight in prohibiting pesticides considered acutely toxic to bees from being applied when flowers are in bloom or bees are present.

Leff’s proposal to shift responsibility is radical, but it is not new; it’s essential elements are contained in the guidance for State Managed Pollinator Protection Plans, a June 2015 document produced by the State The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) Issues Research and Evaluation Group. (SFIREG is a committee of the Association of American Pesticide Control Officials. SFIREG used to have the document on its website, but has since removed it.) Among the six “critical elements” it identified for pollinator plans are methods for growers to know if managed pollinators are located near where pesticides are used and for contacting beekeepers prior to applying pesticides.

Thus it seems that pesticides are sometimes acknowledged to be causing at least part of the decline in pollinators, but the approach proposed by Leff and SFIREG ignores much of what is known — that systemic insecticides like neonicotinoids can harm bees months after application, for example via the planting of treated seeds, and that insecticides are not the only agrichemicals that harm bees. For example, a new study has found that exposure to low levels of glyphosate impairs honeybee navigation. And of course, warning beekeepers of impending pesticide applications does nothing to protect native pollinators (though ostensibly these plans are intended to protect them too).

As the meeting was ending, I was able to pose a practical question: “How easy is it for beekeepers to move their hives when they get a call that pesticides will be applied?” Roberta Glatz, an older woman who serves on the state Apiary Industry Advisory Committee, replied from the audience.

She said that beekeepers aren’t necessarily where their bees are. “They may be in North Carolina raising queens.” She outlined other concerns as well. There are limited places where you can put your bees, and it takes a lot of negotiation to put in a bee yard. Logistics also come into play. Mud can impede access. Hives are heavy and usually have to be moved in the middle of the night when the bees are home. (And beekeepers often have day jobs, another beekeeper told me once the meeting ended.)

So while even the beekeepers of New York are having a hard time getting a fair shake in a protection plan for their own bees, in terms of pesticides it seems that Bombus affinis and other native bees should expect even less of one.

(A version of this article appeared on independentsciencenews.org.)

I hope you found this article important. Before you leave, I want to ask you to consider supporting our work with a donation. In These Times needs readers like you to help sustain our mission. We don’t depend on—or want—corporate advertising or deep-pocketed billionaires to fund our journalism. We’re supported by you, the reader, so we can focus on covering the issues that matter most to the progressive movement without fear or compromise.

Our work isn’t hidden behind a paywall because of people like you who support our journalism. We want to keep it that way. If you value the work we do and the movements we cover, please consider donating to In These Times.