Instead of Enriching Shareholders, These Companies Could Give 8 Million Workers a $46,000 Raise

How public companies like Nike and Apple are shifting money away from workers to the already very wealthy.

Colleen Boyle

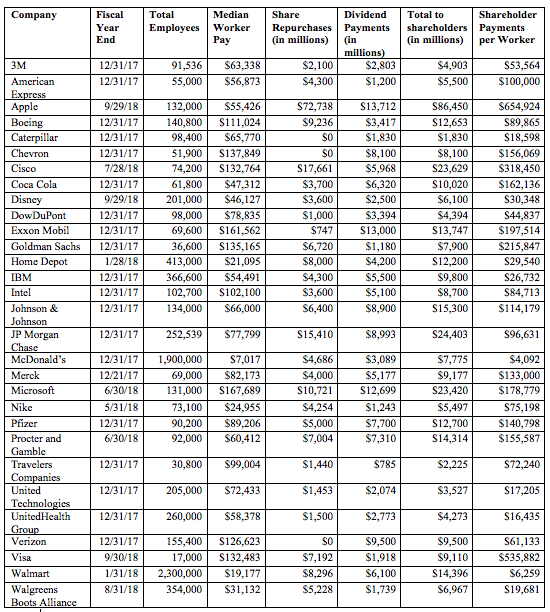

During the most recent fiscal year, the 30 companies that make up the Dow Jones Industrial Average gave $378.5 billion to shareholders. That translates to more than $46,000 for each of their combined 8 million employees.

Publicly traded companies — like Nike, Coca-Cola and Apple — have many options for how to spend their profits. Historically, companies spent their profits reinvesting in their business through research and development, mergers and acquisitions, capital expenditures, and workforce training and increased salaries. Today, corporations are spending the majority of their profits on share repurchases and dividends, which enrich executives and shareholders while stiffing workers.

When companies repurchase shares, the stock price often goes up, which investors like, and which prior to SEC rule changes in 1982 was viewed as illegal price manipulation. In addition, earnings per share increase, a metric that is often used to determine executive bonuses. The rise in the stock price at the time share buyback programs are announced allows executives to sell their shares and profit from their own actions. Research conducted by Securities and Exchange Commissioner Robert J. Jackson, Jr. found alarming evidence of corporate executives using share repurchases to sell their own stock, putting more company money into their own pockets.

In 1982, the Securities and Exchange Commission issued a rule that sets conditions under which publicly-traded companies can repurchase shares without being in violation of anti-fraud provisions. Since then, share repurchases have steadily risen, from averaging 4 percent of corporate net income in 1983, to 27 percent by 1986, and 50 percent from 2007 to 2016. Combined with dividends, corporations spent 92 percent of net profits on shareholder payments between 2007 and 2016.

Meanwhile, real average hourly wages in 2018 are the same as they were in 1978.

If you work for any of these companies, management is choosing to pay you far less than they could. Instead, management is shifting more money to the already very wealthy. The richest 10 percent of Americans own 84 percent of the value of shares of stock. The National Institute on Retirement Security found that 57 percent of working-age adults — over 100 million people — do not have any retirement account assets, and for people with retirement accounts, the median account balance is $0.

In their most recent full fiscal years, 27 out of the 30 companies that make up the Dow Jones Industrial Average repurchased shares, spending a combined $220.3 billion. All 30 companies issued dividends totaling $158.2 billion.

With those payments to shareholders, American Express, Chevron, Cisco, Exxon Mobile, Goldman Sachs, Home Depot, Johnson & Johnson, JP Morgan Chase, Merck, Microsoft, Pfizer and Procter and Gamble all could have doubled worker pay.

For example, Home Depot employed 413,000 workers throughout North America, paying a median wage of $21,095, which was below the U.S. poverty line for a family of four in 2017. But it paid shareholders $12.2 billion, or $29,540 per worker. Home Depot could have doubled worker’s wages and still given almost $3.5 billion to shareholders.

Nike, Coca-Cola and Visa each could have quadrupled the pay of their median employee with the cash they sent to shareholders. Nike paid a median wage of $24,955, which is under the poverty threshold for a family of four, but spent $58,194 per worker on share repurchases and $17,004 per worker on dividends. Coca-Cola paid a median wage of $47,312 but gave shareholders $162,136 per employee. Visa’s median wage was a healthy $132,483, but it gave shareholders $535,882 per worker.

By far the worst example was Apple. For its fiscal year that ended September 29, 2018, Apple spent an incredible $72.7 billion repurchasing shares and distributed another $13.7 billion in dividends. Apple’s median wage was $55,426, while it gave shareholders $654,924 per worker, more than 11 times the median wage of their 132,000 employees.

It’s difficult to quantify the economy-wide impact of this shift in wealth. In 2017, the U.S. median household income was $61,372. Median income for men was $44,408 and median income for women was $31,610. Imagine if several million workers had an extra $10,000 a year to spend on their families. Or $20,000. Or $100,000. Much of that money would circulate in local economies rather than sitting in a small number of investment accounts.

Even if stock buybacks are curbed, as legislation introduced by Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) aims to do, worker wages can still be diverted to dividend payments, or companies can simply sit on piles of cash, as many have been doing. The Reward Work Act also proposes that workers pick one third of the boards of publicly traded companies, which would attempt to address one root cause of the problem: most workers have very little say in what happens to the wealth their labor creates.

A better solution would be to make it easier for workers to join a union. It’s not surprising that income inequality has risen as private sector unionization has dropped. Unions give workers a seat at the table to negotiate how a company’s profits are spent. Right now, with private sector unionization at one of its lowest points over the last 100 years, there’s no check on corporations further enriching the wealthy at the expense of their workforce.

The chart below looks at the most recent fiscal year of all 30 companies that make up the Dow Jones Industrial Average. The analysis, for the most part, doesn’t reflect the higher share repurchases expected to be reported for 2018 due to corporate tax cuts.

Note: The data is for the most recent fiscal year reported on each company’s Form 10-K and Proxy Statement. The median worker pay for each company is what was reported in the most recent Proxy Statement as is now required by the Dodd-Frank financial reform act. There are some limitations to using this figure: Companies include in their calculation workers from around the world and both full- and part-time workers, and companies can include the value of employer provided health insurance and retirement benefits.

I hope you found this article important. Before you leave, I want to ask you to consider supporting our work with a donation. In These Times needs readers like you to help sustain our mission. We don’t depend on—or want—corporate advertising or deep-pocketed billionaires to fund our journalism. We’re supported by you, the reader, so we can focus on covering the issues that matter most to the progressive movement without fear or compromise.

Our work isn’t hidden behind a paywall because of people like you who support our journalism. We want to keep it that way. If you value the work we do and the movements we cover, please consider donating to In These Times.