|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

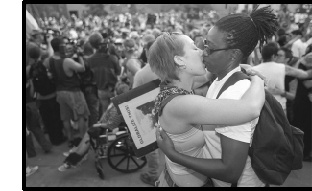

As the danger of wildfires fades across the West, a spate of blazes of a different kind is just igniting. Four states are bracing for battle over ballot measures that could undercut the rights of gays and lesbians. And in a fifth state, Vermont, the fall elections have become a virtual referendum on the first-of-its-kind state law allowing same-sex civil unions. In Maine, voters will decide whether a nondiscrimination act in the offing for more than 20 years and approved by the legislature three different times will finally become law. Meanwhile, in Nevada the electorate faces Question 2, a regressive measure to outlaw recognition of same-sex unions. And in Oregon a diehard gang of gay-rights foes seeks to cut funding for public schools and universities that discuss homosexuality in the classroom. Nebraska, where Initiative Measure 416 would bar same-sex civil unions and domestic

In every locale, the stakes are much higher than the legal status of gays. Referenda on gay issues get people out to vote--especially conservatives--like no other issue besides abortion. With that in mind, progressives in all four states fret that the measures could hinder their efforts to elect allies to the state legislature and retain two Democratic Senate seats. The Nebraska initiative could jinx the Senate bid of former Gov. Ben Nelson, a Democrat who faces GOP Attorney General Don Stenberg in the race for the seat that Bob Kerrey is leaving. In Nevada, Democrats are vying to hold on to the Senate seat vacated by Richard Bryan. Democratic candidate Ed Bernstein faces Republican John Ensign, a former congressman who came within 450 votes of defeating incumbent Sen. Harry Reid in 1998. "Everyone here considers [Question 2] a tool to get the religious right motivated," says Steve Wickson, executive director of The Center, a lesbian and gay community organization in Las Vegas. As donations to the anti-gay Coalition for the Protection of Marriage soar into the high six figures, Wickson says, opponents, led by Equal Rights Nevada, have not tried to keep pace. Their late-starting campaign relies mainly on word of mouth. "It's really a David-and-Goliath fight," Wickson says. In Maine, gay activists likewise hope their coalition proves strong enough to propel Question 6, a nondiscrimination law already approved by the legislature and signed by the governor, to final passage. This year's statewide vote on equal rights for gays is Maine's third in five years. But besides a more organized grassroots base than in previous fights, Maine progressives pushing a "Yes on 6" vote this fall have another advantage: The opposition has image problems. Leaders of the "no" camp were singed this spring when they invited discredited anti-gay researcher Paul Cameron to the state, only to see his past as a defrocked psychologist and advocate for criminalizing various sexual practices backfire on them. Late this summer, anti-gay activists announced plans for a fundraising visit to the state by gay-rights nemesis Jerry Falwell, who, still reeling from his accusations that the kiddie-show character Tinky Winky is gay, will do little to lure fence-sitters to the cause. And at the press conference to launch the campaign against Question 6, anti-gay activist Paul Madore picked a fight with the statewide Catholic diocese, which has come to support gays' pleas for legal protection from bias. The gay-Catholic alliance caps two years of discussions between gay-rights supporters, eager to restore their claim to a popular mandate after failing in a 1998 ballot showdown, and Catholic leaders, vying to regain clout they lost when voters last year rebuffed their drive to ban late-term abortions. In a state where at least one in five voters is Catholic, church support pays more than political dividends. Especially for gays in the closely knit small towns in northern Maine, "having the church's support alone makes a big difference in people's everyday lives," notes gay leader David Garrity. Meanwhile, in Vermont, which lacks a statewide referendum process, partisan races have become a plebiscite on the issue of same-sex civil unions, which lawmakers pushed through in April following a mandate from the state Supreme Court. The public is poised to show its appreciation--or vent its frustration--at civil-union supporters in state legislative elections, including Gov. Howard Dean's bid for a third term, and the U.S. Senate candidacy of openly gay state auditor Ed Flanagan. In most races, the parties have become proxies for the opposing sides. But a few cases defy the rule. Seventeen GOPers in the legislature--driven by principle and revulsion toward fire-breathing civil-union foes within their own party like Randall Terry--voted for the bill. As a result, many faced right-wing challenges in the GOP primary held on September 12. The verdicts were mixed. In the eight most closely watched races for state representative, same-sex union opponents managed to oust four who had voted for the legislation. But Thomas Little, a Republican who co-wrote the bill in the House, survived an upset bid. In the Democratic primary, state Rep. James McNamara, one of the few from his party who voted against the civil bill, lost to candidate Mark Larson, who said he would have backed it. And Flanagan, who had expressed concern that the civil-union flap might dampen his approval rating, eked out a primary win over gay-friendly Jan Backus, who came up short in a 1994 race against moderate GOP incumbent James Jeffords. In Oregon, the anti-gay proposal hearkens back to a bygone era in both its tone and title. The so-called Student Protection Act would take away state funding for any public school, pre-kindergarten to graduate-level, whose curriculum mentions homosexuality or bisexuality in anything but negative terms. It is the brainchild of the Oregon Citizens Alliance (OCA), a group of social conservatives who led a failed drive to hijack the state GOP in the early '90s. In their most visible defeat, the OCA sponsored a 1992 statewide initiative called Measure 9 that would have declared gays "abnormal, wrong, unnatural and perverse." After a wrenching campaign that saw two gay people die in an attack by skinhead arsonists and the sanctuary of a gay-supportive Catholic Church defaced by "Yes on 9" graffiti, the OCA measure lost at the polls, drawing only 43 percent of the vote. Now, in a fluke of the electoral lottery, the current OCA measure will also appear on the ballot as Measure 9. The oddity has led longtime gay rights activists to dust off campaign signs packed away eight years ago and re-arm after more than a decade of battle with a discredited but dogged foe. With its focus on education, the current measure paves the way for a broader coalition than has confronted the OCA in the past. No sooner had Measure 9 qualified for the ballot--barely, after a second tally of signatures by the Secretary of State's office--than the 27,000-member Oregon PTA entered the fray against it. "They don't scare us anymore," says Greg Asher, a veteran of the political fights with the OCA. "What angers me today is how much effort and expense it requires from the gay community to counter these measures." Still he urges activists not to panic and to focus on the big picture:

"Don't fear the discussion. As it emerges, go into it. And remember:

There's no issue that will drive us back into the closet."

|