|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Me, You, Them A Time for Drunken Horses George Washington The Toronto International Film Festival, which celebrated its 25th anniversary in September, is now an event that ranks with Cannes, Venice and Berlin. Loaded with starpower (Pacino, Gere, Paltrow), and glossed with glitz, it's also an astonishing demonstration of the range of filmmaking worldwide. There's the shamelessly spectacular, like Taiwanese Ang Lee's romantic costumer set

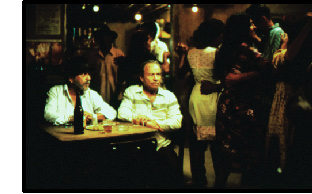

Some of this global cinematic cornucopia spills out into American cineplexes, defying the truism that Americans don't watch foreign films and never read subtitles. That's partly because conglomerates have snapped up and launched their own art-house distributors (Miramax, Sony Classics, Screen Gems, Universal Focus, New Line and so on), which are stocking the unprecedented number of movie screens. The global nature of the cinematic marketplace makes even a money-losing theatrical launch part of a long-term, global marketing plan that can pay off down the line. These new facts of life in the film business have made it possible to market a new hybrid product: the little international charmer of a movie, heralding from somewhere that doesn't make the front page of the Times, perhaps somewhere exotically post-colonial, and celebrating the struggle of good people to endure. These movies can be lush and sexy (Like Water for Chocolate, from Mexico), mournfully dramatic (The Color of Paradise, from Iran), knowingly funny (East Is East, an English film about the South Asian diasporic community in Britain), a downright hoot (The Full Monty, about English steelworkers displaced by globalization) or handsome as handsome can be (like a whole run of Chinese films from the so-called Fifth Generation directors). They take the traditions established by neorealist directors in the '40s and '50s--who in films as diverse as The Bicycle Thief and Pather Panchali awakened viewers' demands for common human decency--and create a new movie formula. Me, You, Them, by Brazilian director Andrucha Waddington, is a nicely burnished example of the new, farm-bred international charmer. Set in Brazil's impoverished northeast, it builds on tradition. In the '60s, Brazilian "new cinema" was an angry example of Third World neorealism. Directors such as Nelson Pereira dos Santos (Barren Lives) and Glauber Rocha (Black God, White Devil) rocked international audiences and horrified Brazil's military government with films that featured a northeastern peasantry that was suddenly stirring politically. After a miserable decline hastened by censorship, persecution of artists and a failure to protect local markets, in the '90s Brazilian cinema was revived as a commercial enterprise. Two years ago, the Brazilian feature Central Station, about an embittered old woman and an orphan who search the northeast for a way to go home, became an international award winner and box office pleasure. Me, You, Them is based on a true story of bigamy among the peasantry. We meet Darlene (Regina Casé) who, pregnant in a makeshift wedding gown, is stood up at the church door; she takes the next bus out of town. Three years later, she returns just in time for her mother's funeral. She accepts an offer to wed from surly storekeeper Osias (Lima Duarte), and proceeds to make a life out of hard work in the cane fields and at home. Her sexiness defies the dirt, misery and cruelty of her condition; her next baby looks nothing like her husband, creating suspicion and deepening her husband's brutality. Her efforts to flee Osias' abuse fail, and she returns, having given her oldest son to his father--her foreman in the cane fields--so that he can be educated. When her shy, single brother-in-law (Stenio Garcia) comes to stay, she finds sympathy and some help in the kitchen; soon he gets a son. Their peculiar arrangement works until a handsome new worker (the very hunky Luiz Carlos Vasconcelos) shows up in the cane fields. Then everyone has to consider the terms under which they will accept a little happiness in a life that is otherwise ruled by utter deprivation. The true story from which the movie is derived was a tabloid treasure, since it so titillatingly teased the terms of the region's patriarchal culture. It played not only with the ruling ideology that women are the property and subjects of men, but its companion ideology that women also exercise a mystical power over men, through their sexuality and their control of childbearing and domestic life. The film also plays, more discreetly, with these assumptions, and Casˇ's ability to project a sexy companionability carries the game a long way. But the film never really strays far from the terms of patriarchal culture, nor does it ever challenge the economic or political injustice that reinforce it and still make it perfectly possible to get away with wife-murder in the region. It's simply up to the characters to make stone soup of it all, and the director says as much. "Me, You, Them is a film about ordinary human beings in a situation considered absurd, in a society that does not accept polygamy," Waddington told a Brazilian newspaper. "I would also say that it's a film about the rules of the game, and of how life presents new rules every day. If people want to be happy, they have to adapt themselves to the new rules, even if they have to go through moments of real misery." So there it is: neorealism nouvelle, a tasteful addition to the global cinematic palate. In the backlands, just like in the high-tech dotcom environment, flexibility is everything. Adapt to polygamy if that's how you can hold on to your joie de vivre while starving. Other features at Toronto took the grand legacy of neorealism in other directions. Consider A Time for Drunken Horses. The film, set in Kurdistan, was made by Iranian director Bahman Ghobadi, who grew up in the region. The Iranian government both supports and yet suppresses a highly productive, professional cinema. Over the years, it has become well known for films featuring children, with stories that wend around many of the political unsayables. Some are more cloying than others, but a few--such as Abbas Kiarostami's Where Is the Friend's Home, Samira Makhmalbaf's The Apple and Children of Heaven by Majid Majidi--have been splendid. Ghobadi's film takes place in mountains dotted by Kurdish villages (Kurds are the largest stateless group in the world) divided by the national borders of Iran and Iraq. In a village that survives by smuggling simple domestic goods across borders, a family is orphaned when the father is killed by a buried landmine. The children rally to save their ailing handicapped brother; and finally the teen-aged eldest brother, hoping to earn money for the child's operation, sets out on the smugglers' route, through landmine-laced terrain so terrifying that horses must be fed whiskey even to attempt it. The landscape is as forbidding as it is majestic, and the desperate hope of the young people is as poignant as the adults' resignation is terrible. Ghobadi's film takes a genre that has become all too formulaic, and renewed its power. George Washington--which will have a modest run in large cities this fall--is one of those movies that astonishes you with the strangeness of ordinary life. Made by David Gordon Green, a 24-year-old film school grad in North Carolina, it takes a group of young teenagers in a small, down-at-heels industrial town in the South through a Fourth of July weekend. In that time, one of them will die, two will tempt fate, and George, the 13-year-old African-American kid at the middle of the story, will survive. It's shot in 35 mm in a way that makes you feel Southern heat and industrial rot, but lets you see with young eyes the wonder of a day, a night, a dog or a girl; it brings the term magical realism back to cinematic life. Green, who is white and who grew up in such a town, has won some

entirely fresh performances from young non-actors. The film is uneven;

the dialect is not always comprehensible, and the final cut clearly

left some story pieces on the floor. But when you leave George

Washington, you've watched an emerging artist who illuminates

a world; you've been reminded of the many things beyond the business

deal that festivals are for.

|