|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

When Bill Ryan started visiting Death Row prisoners in Illinois some five years ago, he got a lot of unsympathetic reactions from friends. "It used to be that I would talk about being opposed to the death penalty and people would look at me like I was crazy," says Ryan, a retired social worker who helped form the Illinois Death Penalty Moratorium Project in 1996. "I live in suburbia, and there are a lot of very conservative people out here. They'd look at me like I was nuts." No longer, he says. For death penalty activists, the landscape has undergone a sea change in a very short

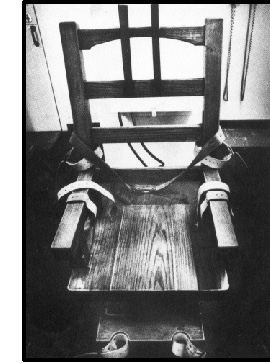

Now, particularly after Illinois' pro-death penalty Gov. George Ryan declared a moratorium on executions in that state, the movement to end the death penalty has been catapulted forward. Six states are currently conducting reviews of their capital punishment systems, as is the federal government. Both chambers of the New Hampshire state legislature voted to abolish the death penalty in that state (though the measure was vetoed by the Democratic governor). Moratorium legislation is pending in Pennsylvania, Ohio, New Jersey and Missouri, and similar bills have been introduced in 10 other states over the past two years. A spate of city governments have passed resolutions supporting moratoriums. In Congress, several bills are pending that would impose moratoriums or institute safeguards against wrongful convictions. For the first time in decades, it's arguable that abolitionists have the upper hand. How things arrived at this point is a combination of hard work--on the part of activists, lawyers, journalists and the civil rights and religious communities--and, as in any movement, an element of timing and luck. A look at how the movement to abolish the death penalty has changed gives insights into how strong the movement is--and where it might be headed. Last year 98 people were executed in the United States--more than in any year since death penalty laws were put back on the books in 1976. By comparison, 63 people were put to death in the entire decade after the death penalty was reinstated. Executions have seen their sharpest increases in the '90s, as have the rolls of Death Row inmates (currently at more than 3,600). According to Amnesty International, only China and the Democratic Republic of Congo executed more people than the United States in 1998, and this country is the world leader in executions of prisoners who were under 18 at the time of their capital crime. The increase in executions and death sentences can be traced to a politically motivated get-tough-on-crime spree embraced by politicians from both major parties that dates back to Nixon and went through a revival in the early '90s. "The death penalty was the poster issue of the whole tough-on-crime movement," says actor and activist Mike Farrell, president of Death Penalty Focus in California. In 1988, the federal death penalty was revived for murder committed in the course of large-scale drug trafficking. Under President Clinton, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 expanded the federal death penalty to some 60 additional crimes, including several that didn't involve murder: treason, espionage and large-scale drug trafficking. Two years later, following the Oklahoma City bombing, Clinton signed the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. In an effort to shorten the amount of time between conviction and execution, the law established tighter filing deadlines, limited the opportunity for evidentiary hearings, and allowed only a single habeas corpus filing in federal court. It was passed a year after Congress eliminated all federal funding for post-conviction capital defense organizations, which had assisted Death Row inmates in habeas proceedings. The outlook even a few years ago was bleak. "You'd go to executions--I even went to double executions--and nothing was happening," Bill Ryan says. "It was frustrating." What has happened since is all about critical mass. "A confluence of events came to a head," Farrell says. "There was the conference on the wrongly convicted at Northwestern University in Chicago, the whole explosion of the issue of innocents on Death Row, Governor Ryan's decision to declare a moratorium, the Chicago Tribune's articles, the movie of Sister Helen Prejean's book Dead Man Walking--there were so many things that were happening. All of these things kind of collided at a time and ... people suddenly began to wake up. And I think it has established a momentum that in my view is irreversible." This has left activists somewhere between dumbstruck and giddy. "It was like they finally heard us," says JoAnn Patterson, mother of Illinois Death Row prisoner Aaron Patterson, who has worked with the Illinois Death Penalty Moratorium Project. Bill Ryan adds that for the first time in his five years working on the issue, it feels like he's part of a movement. "I didn't think it was a movement until the last six or eight months," he says. "But it's fast becoming a movement." For the past three decades, the foot soldiers in the movement against the death penalty have worked out of churches and makeshift home offices. They've maintained a consistent presence at executions, drawn attention to the wrongfully convicted, and undoubtedly saved dozens of lives. At times they've put enough people in the streets--particularly in the case of Pennsylvania Death Row prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal--to attract media attention. But despite being able to mobilize thousands and attract international support, abolitionists were unable to get mainstream Americans to buy into their cause. Abolitionists haven't suddenly won the ear of Americans because they're presenting new arguments. "Eighteen years ago when I started investigating these cases, nobody would pay any attention," says Rob Warden, executive director of Northwestern University's Center for Wrongful Convictions and former editor of Chicago Lawyer, where seven of the first 10 wrongfully convicted Death Row prisoners in Illinois were first exposed. The Death Penalty Information Center has a library of studies--some of them nearly 10 years old--that bring up issues only recently catapulted into the public consciousness and being seriously reviewed: innocents on Death Row, prosecutorial misconduct, ineffective counsel. So why now? More than anything else it has been the recent parade of exonerated men marching off of Death Row--13 of them in the past two years--that has triggered movement on this issue. "The issue of innocence, the presence of a number of innocent people who have been freed from Death Row and stories people have now heard--that convinced people outside of the usual opponents that there was something wrong," says Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. The debate over the death penalty, which in the past has focused on ethics and morality, now centers on the justice system as a whole. "I don't think that people are being morally convinced that the death penalty is wrong ," Dieter says. "That's not what's changing. What's changing is a practical, fact-based concern about how the death penalty is applied. That's where the numbers are shifting." That has meant that abolitionists are suddenly finding they may have at least temporary new allies in the fight who have no moral objections to the death penalty. George Ryan has repeatedly said he believes the death penalty is a reasonable societal response to the most serious crimes, and his Governor's Commission on Capital Punishment is charged with making "recommendations and proposals designed to further ensure the application and administration of the death penalty in Illinois is just, fair and accurate." After an August public hearing before the commission, where all but one of the 47 speakers voiced opposition to the death penalty and detailed concerns ranging from medical doctors' participation in executions to what one assistant public defender called "the inherently arbitrary nature of the death penalty," the Chicago Tribune editorialized that the commission's first public hearing was a "disappointment," where "dozens of death penalty foes dominated the speaker list, overloading the hearing with repetitive rhetoric rather than thoughtful insights into specific problems." The Tribune went on to say that the commission's mission "is to provide specific ideas for reform, not a recommendation on whether to keep the death penalty." The possibility that the steam in their movement might be diverted to try to create a system that kills only the guilty and protects the innocent has not eluded activists. Lawmakers and others who have benefited politically from supporting the death penalty, Farrell says, have sensed public concern and have thus taken up the issue, but are "eviscerating the moratorium by insisting on 'reform.' " It could even be questioned that the notion of a moratorium is already a dilution of the stronger stance of abolition. That's something that doesn't seem to worry most abolitionists. "Abolition and a moratorium--it's the same thing in essence," says Robert Drinan, a Georgetown University Law School professor and a columnist for the National Catholic Reporter who has written about the death penalty. "If you have a moratorium it is unlikely that you'll ever go back and execute people. And that's why the American Bar Association chose a moratorium. We didn't urge the ABA to advocate for abolition because we didn't have the votes. But a moratorium means that you look at this thing and then you discover that it's indefensible." Drinan's confidence that abolition is the only logical outcome of a careful study of the death penalty--even if that study's avowed goal is to reform the system--is shared almost across the board by activists. "I don't worry about a fair examination of the death penalty," Dieter says. "It is one of these things that has some very inherent problems that are going to be very difficult to fix." But activists' confidence is not necessarily shared by others. "I think there's a very good possibility that you'll see executions resume in Illinois," says Chicago Tribune reporter Steve Mills, who co-authored the series "Failure of the Death Penalty in Illinois" as well as a recent investigative series on Texas' capital punishment system that ran the week before Gary Graham's execution. "I think it would be pretty hard to come back and say, 'OK, We fixed the system. Now let's go ahead,' " Mills says. "But I think it's possible that politicians will say that." Former Illinois Sen. Paul Simon, who co-chairs the Governor's Commission on Capital Punishment and opposes the death penalty, says a pragmatic approach is better than nothing. "Part of the legislative process is you do what you can and you don't always win 100 percent," he says. "If the commission can reduce the number of executions in the state, is that going as far as I'd like to see it go? No. But is it worthwhile to save some human lives? Yes." Changes in public opinion may allow politicians an opportunity to reconsider their stand. A Gallup poll taken in February registered support for the death penalty at a 19-year low; but that just means support is overwhelming, rather than nearly unanimous: 66 percent surveyed said they favored the death penalty for people convicted of murder. But recent polls are showing that similar majorities support a moratorium on executions. In a nationwide, bipartisan poll released by the Justice Project in September, 64 percent of those surveyed said that they favored suspending the death penalty until its fairness could be studied--in light of Death Row prisoners who have been released based on new evidence or DNA testing. The San Francisco Chronicle reported in June that 73 percent of voters surveyed in California--which has the largest Death Row in the country--are in favor of suspending executions to study the fairness of the state's capital punishment system. And even in Texas, which accounts for 33 executions so far this year (about half of the national total), a Houston Chronicle survey showed that 3 out of 4 respondents said the state should declare a moratorium on death sentences in cases that might be affected by DNA testing. In a year when the Democratic Party might have anticipated a shift in public opinion on this issue, it went in the other direction and inserted a pro-death penalty plank in the formerly neutral platform. Al Gore has been a longtime believer in the death penalty, though he did admit feeling "uncomfortable" with the findings of a Columbia University study released in June, which showed that in two of every three death penalty cases between 1973 and 1995 the sentence was reversed on appeal because of errors. George W. Bush largely has escaped public criticism, despite his sardonic public comments (such as the Talk magazine interview in which Bush mimicked Karla Faye Tucker pleading for mercy before her execution) and loud claims that Texas may have executed innocent prisoners on his watch. Bush has plowed ahead with state killings in Texas, signing off on execution orders at the rate of about one per week during the presidential campaign. Executions are scheduled for the two days following the election. With the innocence issue playing such a central role in the shift in death penalty politics, there is one obvious remaining task for abolitionists--to prove that an innocent person has been executed. That's the Holy Grail in this fight, and perhaps the one thing that could irreversibly alter public opinion on the death penalty. Academics, activists and attorneys have suggested the names of dozens who have been executed despite substantial doubts about guilt, but lack of evidence hasn't been their biggest obstacle. "We've allowed the other side to define innocence," says Warden of the Center on Wrongful Convictions. "And basically they've defined it by saying, 'The innocent person is who we say is innocent. We say nobody is innocent; therefore, nobody is innocent.' " Prosecutors have fought hard to prevent post-execution DNA testing. After Joseph O'Dell was executed by Virginia in 1997, the Catholic Diocese of Richmond requested samples for DNA testing--testing courts had refused to allow before O'Dell's execution. Arguing against turning over the samples, state prosecutors maintained that "people will shout from the rooftops that the Commonwealth has killed an innocent man" if DNA samples from the victim did not match blood found on the clothing of the executed. The court ordered the DNA evidence destroyed. Lawsuits in several cases are currently pending to allow for DNA testing in post-execution cases. But Warden says that even in a case where DNA points to innocence, prosecutors would still insist they executed the right man. "The guy may have been convicted of murder and rape and sentenced to death," he says, "and DNA might even establish that he could not have been the source of the semen, and the prosecutors will say, 'Well, she could have had consensual sex with someone else.' " He quips: "We are referring to that now as the 'unindicted co-ejaculator theory.' " However, it's unclear whether proving that an innocent person has been executed would matter to Americans. In the same February 2000 Gallup poll in which 66 percent of those surveyed said they were in favor of the death penalty, 91 percent said they thought innocent people had been sentenced to death in the past 20 years. In another poll released at the end of June, 80 percent said they believed an innocent person has actually been executed in the United States in the past five years, and still 66 percent favored the death penalty. Warden says that despite the current avalanche of events that seem to be lining up in abolitionists' favor, Americans' views on the issue--and politicians' actions--are largely incident-driven. And while exonerated Death Row prisoners have dominated the news lately, all it may take to turn back the tide would be one prominent serial killer. For now, those working in the legal, political, organizing and

religious arena--whose work, Warden says, has been behind every

exonerated Death Row prisoner, Illinois's moratorium, investigative

reports and legislative initiatives--will continue their labors

in a more amenable, if fragile, climate. "The momentum is all there,"

Warden says. "But the wind can change." Linda Lutton is a Chicago-based freelance writer.

|