|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

C. Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings At his untimely death in 1962, C. Wright Mills seemed well on the way to advancing from the first rank of American sociologists to the first rank of world intellectuals. In the great trilogy he published between 1948 and 1956--The New Men of Power, White Collar and The Power Elite--he had issued a lacerating critique of what he expansively called "this whole setup." The books' overarching themes were the continued division of American society into classes with sharply divergent, even antagonistic, interests and aspirations, and the central role of coercive power--not shared values--in holding those classes together. It was a bracing message for any time, and especially for that one; its ability to find and hold a mass audience--and it did, to an extent unmatched by anything else that could be remotely considered sociology--was no doubt helped by Mills' central concern for the moral qualities of life in the society he described. It was this, even more than their literary stylings, that set his books apart from the sociological mainstream. As he put it in the long letter to an imaginary Russian colleague that forms the "autobiographical writings" component of the new collection C. Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings, in all his work he sought "some kind of combination answer to Lenin's question: 'What is to be done?' and Tolstoy's: 'How should we live?' " The trilogy--especially its first two volumes--won Mills esteem from his academic

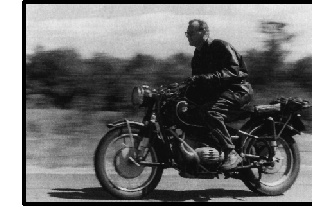

Alongside Mills the scholar and Mills the pamphleteer was Mills the biker, the defiant individualist in the age of the Gray Flannel Suit, who came roaring up to his Columbia University offices on his BMW motorcycle in work shirt, jeans and boots. "Take it big," he advised students and colleagues, and he always did, in his life as much as his work. After his death more than one friend described his habit, after finishing dessert at one of the Manhattan steakhouses he loved, of calling to the waiter, "That was good--I'll have the same thing again," and working his way through another full meal. One recalls that Thomas Wolfe, no slouch himself at a typewriter, said that sitting down to write each day was like starting a new, enormous meal after eating to satiation. No surprise then that Mills, who died at only 45, was able to write four big books and four small ones, edit or co-author three more, and produce a major translation of Max Weber, a fat stack of scholarly articles and enough topical writings to fill a volume of 650 pages. The letters are at their best displaying Mills' outsize personality. Almost every page--even the peevish complaints to publishers that any representative collection of a writer's letters must include--conveys energy, vitality, immense animal spirits. "Play the guitar an hour or so at night. Read more and more on movies," he reported to his editor William Miller in 1949. "My god what a thing they are. We must make them: they've got everything that appeal to me in this damn society and moreover the chance to damn everything else in it. Will write one this summer. ... The title of the movie to be written is: 'Enthusiasm.' " He goes on (and on and on) about his enthusiasms: his motorcycle, his houses (which he built--three of them--from the ground up), his photography, anything he could do with his hands. After 300 pages, one ends with an impression of Mills that, if without much breadth or context, certainly doesn't lack for intensity. Among other things, the letters make clear Mills' determination to write books with literary as well as scholarly value. As he put it to his parents, White Collar was to be "my little work of art: it will have to stand for the operations I will never do, not being a surgeon, and for the houses I will never build, not being an architect. So you see, it has to be a thing of art and craftsmanship as well as science." His comments on the craft of writing in these letters fit well with those in his published work, especially The Sociological Imagination with its well-known evocation of "intellectual craftsmanship." There, Mills warned against both Grand Theory and "methodological inhibition," the fetishization of techniques of data collection. Instead, theory and method are to be treated as scaffolding: vital during the construction process, but no longer present--or at least not visible--when the building is done. The most "useful discussion of method as well as of theory usually arises as marginal notes on works-in-progress or work about to get under way," he observed. When Mills obeyed his own strictures--and he generally did--the results could be impressive. All but the most colorful or exemplary evidence is hidden in footnotes (or in the author's files); any self-conscious theory is too, or is effaced entirely. The effect is of a mirror held up to the world; Mills' best books read not like sociology, but like great novels (Balzac and Dos Passos were his models). "What I want to say," he explained to Miller, "is what you say to intimate friends when you are a little discouraged about how it all is. All of it at once: to create a little spotlighted focus where the alienation, and apathy and dry rot and immensity and razzle dazzle and bullshit and wonderfulness and how lonesome it is, how terribly lonesome and rich and vulgar and god I don't know." By this standard he often succeeded brilliantly. In the tradition of the great American sociologists of the first half of the century--Park and Burgess, W.E.B. DuBois, Carolyn Ware, the Lynds--Mills wrote real books, intended not to argue a thesis but map out a social totality. (Mills was in but not of this tradition: He always presented himself as an untutored Texas "mushroom," and none of these predecessors except fellow Columbia professor Robert Lynd, one part mentor to three parts rival--Mills sarcastically referred to him as "God"--show up in the letters or in Mills' major books.) What makes Mills' books so intoxicating to read is the way they deploy every possible form of evidence--statistical sampling, in-depth interviews, literary and historical material--in support of a single overarching vision, one that constantly connects the "feel and tang" of individual experience with a rigorous account of institutions. It's hard to think of any recent work of sociology where the scholarly machinery is so well-oiled and works so discreetly and noiselessly out of view. Mills' best books fully deserve the label he applied to James Agee's Let Us Now Praise Famous Men--sociological poetry. Why don't more social scientists write like Mills today? In fact, there are some good reasons. Social scientists foreground method and evidence to allow their conclusions to be independently verified; they foreground theory to position themselves within debates in the field. Neither can be lightly dispensed with if one wants to be part of the larger scholarly division of labor. But then, that's exactly what Mills didn't want. He expected his books to be taken seriously as sociology, but he never wrote for sociologists or let them set his problems. The audiences he cared about were New York intellectuals first and foremost, and then the public in general; the reviews that got him worked up were in Politics and Partisan Review and The New Republic, not American Sociological Review. Late in his life, he dropped even the pretense of being part of the academic fraternity, and became increasingly enamored of the image of the unaffiliated intellectual speaking truth to power. Sociological poetry, yes; but his work also deserves the description he applied to that of Marx: "It tries to be social science all by itself." Mills' dream of scholarly self-sufficiency is, in some ways, at the heart of his whole outlook. This is a man, after all, who boasted that he could build his own house with nothing but wood, wiring and a few sheets of glass and tin ("if wood isn't available I can cut timber and wait a year and build with that"), and who built his own motorcycle, in a workshop in Germany. ("It is very proper," he wrote to his old professor Hans Gerth, "that no intellectual group or agency should send me to Europe but that I should smell it for the first time as an amateur mechanic.") In his political interventions, too, he made a point of being on his own, of having no clearly defined constituency. He called himself a "politician without a party"; one has only to read The Causes of World War Three, which issues its great rolling pronouncements with supreme indifference to what agency will carry them out, to see how seriously he took that designation. "Way down deep and systematically I'm a goddamned anarchist," he wrote to Harvey Swados; it was Mills who unearthed the old Wobbly slogan, "We are all leaders." Some of his most eloquent passages, both in the letters and in his published work, are paeans to the craft ideal. As an ideal, the appeal of the autonomous craftsman can't be denied. But how can one recreate this kind of autonomy without also restoring its material basis--the standard of living of 150 or more years ago? When production requires the coordinated efforts of a great number of more or less specialized workers, how is unalienated work possible? These questions are not unanswerable, but Mills never seriously tried to answer them; instead "craftsmanship" became a fantasy, an evasion of modern realities. For of course, Mills didn't really build his motorcycle; he assembled it from parts built by thousands of others; despite his boasts, the houses he constructed were similarly the product of an extensive division of labor. Self-reliance in political and intellectual work is equally illusory--a fact Mills was never quite willing to accept. Indeed, if one pole of his thought was the hierarchical and regimented social universe presided over by "the sons of bitches who run American Big Business," the other, as these letters make clear, was the Greenwich Village coffeehouse milieu of the Beats. There the highest value was personal integrity and self-discovery rather than any collective end. In this respect, as much as in his political stances, Mills anticipated the New Left and the counterculture. "There is a certain type of man who spends his life finding and refinding what is within him," he wrote cheerfully to his parents as a graduate student. "I suppose I am of that type." It is a type that has become all too familiar in the decades since. Mills' uncritical embrace of individual craftsmanship, intellectual and otherwise; his faith in the political power of personal integrity ("the politics of truth," he called it); and the leading role he envisioned for intellectuals all grew out of the same feature of his thinking: a lack of any idea of what a politically mobilized society might look like. In the '40s, he still saw the labor movement as containing at least the germ of a new kind of autonomy, one suited to industrial society; unions, he wrote, were "the only organizations capable of stopping the main drift toward war and slump." (The wording is important: It's not just that bad outcomes are to be avoided, but that drift is to be replaced with conscious mastery. Here as so often, Mills expressed Marxist ideas while avoiding Marxist jargon.) For Mills, as for many on the left both in the United States and Europe, the failure of the organized working class to lead the struggle for social transformation meant that his vision of a different world was left unconnected to any plausible agent of historical change. For some, this was a signal to abandon politics; Mills, to his credit, retained his radical views, but his thinking acquired an increasingly utopian tinge. Nor did this problem disappear when the Cuban revolution again offered Mills something concrete to be for. It's important to remember that Mills was on the side of the angels with regard to Cuba, a position that took real courage. Though his outspoken support for the revolution won him many friends, especially in Latin America, it also earned him intense official hostility, which may well have hastened his death. Still, it's strange to see the Cuban revolution being praised as, in effect, an upsurge of Emersonian individualism, a movement without theory and, at its best moments, without leaders. Whatever was needed, the people would simply do. Mills was right to defend Cuba, but couldn't he have done so without falling back on the shopworn tropes of revolutionary authenticity and spontaneity? "Just do it" is hardly the exclusive faith of the left, of course. In his idealistic individualism, in his distrust of theory and bureaucracy, Mills was right in the American mainstream. His first scholarly interest was in the pragmatists, and as his biographer Irving Horowitz rightly points out, pragmatism never left the center of his political thought--which, Horowitz should have added, is too bad. As a theorist and chronicler of social hierarchy, Mills is still immensely valuable to anyone who wants to understand a system in which the exercise of power is ubiquitous but not always easy to see. And as a writer, he's certainly to be admired and learned from, if only emulated with caution. But it's mainly the Beat sociologist, Horowitz's "American utopian," who comes through in these letters. That Mills can be read for inspirational effect, if your tastes run that way; otherwise, he is only of historical interest, a missing link between Dos Passos and On the Road. "You ask for what one should be keyed up," Mills wrote at one point to Gerth, who was feeling blue. "My god, for long walks in the country, and snow and the feel of an idea and New York streets early in the morning and late at night and the camera eye always working whether you want or not and yes by god how the earth feels when it's been plowed deep ... and yes by god the world of music which we just now discover and there's still hot jazz and getting a car out of the mud when no one else can." Dean Moriarty couldn't have put it better. J.W. Mason wrote "Dancing in the Suites" in the September 18 issue.

|