|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

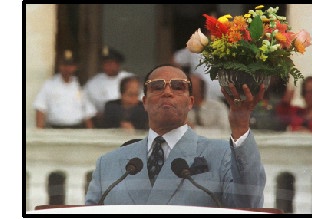

When Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan announced last December that he was moving away from the racial focus that once defined his mission, he provoked a minor earthquake in the black community. At a press conference held at the group's main mosque, Farrakhan said a "near death" experience resulting from prostate cancer treatment caused him to refocus his views on uplifting "fallen humanity regardless of their race, color or creed." His brush with death may have hastened his move away from the eugenic theology that

But while Farrakhan's move toward the mainstream may be heartening to his erstwhile critics, it's causing considerable anxiety among many African-Americans. Since Malcolm X gave the Nation a national identity in the early '50s, the group has distinguished itself as an organization irrevocably dedicated to the cause of the race. Other African-American organizations may have adopted aspects of black nationalist ideology or mouthed slogans of self-reliance, but for Elijah Muhammad's Nation, "blackness" was not just a racial identity, it was an ontological principle. The Nation of Islam was a hard sell for most African-Americans. The ascetic behavior code, the need for sartorial and intellectual conformity and the rigorous diet were too demanding for most, but the group earned street-level credibility through its success in reaching those deemed unreachable. The public arrival of Malcolm X upped the group's profile and influenced the future direction of the black liberation movement. He gave impetus to the cultural nationalist movement with his rhetorical embrace of African culture; he also nurtured the "revolutionary" nationalist movement (like the Black Panther Party) by focusing on anti-colonial struggles in the Third World. In his later years, he helped boost support for socialism even as he increased the visibility of orthodox Islam in the black community. Although Malcolm X's later fame came after his public and rancorous estrangement from the Nation, his wide influence placed the group at the heart of the discourse surrounding the black freedom movement. Farrakhan inherited much of that influence, but he also was burdened with the Nation's thuggish reputation. He sided with Elijah Muhammad in his public disagreement with Malcolm X, and Farrakhan was tainted by his presumed connection to Malcolm X's 1965 assassination. He has worked assiduously with the black nationalist community to minimize that long-standing animus. In April 1995 he met with Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X's widow (who later died in a house fire), in a public reconciliation at New York's Apollo Theater. And yet, just as Farrakhan has gained the confidence of the disparate nationalist community, he is moving away from nationalism. "I could never abandon the struggle of our people for justice and freedom," says Farrakhan when asked if he is abandoning nationalism. But he adds: "I have to recognize the universality of the religion of Islam, and I have to recognize the need for a better life, not only for us black people." Farrakhan says the racial emphasis of the early Nation of Islam was a reaction to the white supremacy that permeated the culture at the time. He notes that many black people joined the Nation for racial rather than religious reasons. "Most of us were nationalist, but we accepted Islam," he explains. "We accepted a nationalist version of Islam, which was proper and right and fitting in the condition that we were in. Even Jesus started very narrowly." But there are many in the black community who feel that African-Americans are still vulnerable to white supremacy and need the countervailing influences of black nationalism. "I hear a lot of people who are very nervous about what Minister Farrakhan is doing," says Cliff Kelly, host of a popular talk show on WVON, a black-owned Chicago radio station. "My listeners aren't sure that we've got ourselves together enough yet to begin reaching out to others." Kelly, who says he was a wholehearted supporter of the Million Man March, was considerably less enthusiastic about the Million Family March. "Had it been the 'black family march' I might have been more supportive. But I'm not ready to join with others just to say I joined with others. It seems to me that we will continue to lose in any coalition where we have nothing to bring to the table." Many in the black community who feel unsettled by Farrakhan's new ecumenicalism echo Kelly's sentiments. Some of these anti-Farrakhan feelings are tinged with hypocrisy: Many who now condemn Farrakhan's de-emphasis of nationalism once were critics of that very same nationalism. Still, if such sentiments are common within the larger community, it's reasonable to assume that they are magnified among the legion of Farrakhan admirers who were attracted to him precisely because of his audacious black nationalism. "I used to say that I would be down with Farrakhan, no matter what," explains Karimah Cannady, a former Nation of Islam member from New Jersey who has remained an admirer of Farrakhan. "But when I see his alliance with the Moonies [the Rev. Sun Myung Moon's Unification Church] and his flirtation with Lyndon Larouche and folks like that, I begin to question his judgment." Farrakhan insists that the Nation never has formed an alliance with Larouche, the anti-Semitic conspiracy theorist, though members occasionally have attended conferences organized by his followers. "We go, we participate and we listen to learn," Farrakhan says. However, Farrakhan is much closer with Moon. Financial incentives may help smooth their relationship; the Unification Church reportedly footed a significant part of the bill for the Million Family March. "We have not formed an alliance as such, but there's mutual respect," Farrakhan told In These Times. "I respect the work Rev. Moon has done. The man's work and his influence are tremendous. All the things the Honorable Elijah Muhammad taught that he wanted us to do, the Rev. Moon and his followers are doing." The 67-year-old Farrakhan's incongruous attraction to black youth also seems endangered by his new moderation. The very qualities of audacity that set him apart from the conciliatory (read: "sellout") leadership that black youth decry are being downplayed in his new image. It's unlikely that rap artists will find much of value to sample in his new sermons on religious and racial unity. Other black groups so far are reluctant to comment on the importance of Farrakhan's changing emphasis until they see how it plays out within the Nation of Islam itself. "I'm not really sure what kind of effect Farrakhan's new direction will have on the black community," says Robert Starks, a professor of political science at Northeastern Illinois University's Center for Inner City Studies in Chicago and chairman of the Task Force for Black Political Empowerment. "I think his moves will have more of an internal effect on the Nation, than in the black community at large. As far as I know, he won't be changing any of his current emphasis on economic independence and community empowerment." But the Nation has influence far beyond its membership, and the group's internal divisions often play out in the larger society--too often in destructive ways. The conflict between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad is just one example of how an internal dispute provoked divisions among black activists that lasted more than 30 years. While Farrakhan seems headed toward orthodox Islam, he also is becoming more explicitly political. His public appeals for attention from the two major parties, and his overtures to vice presidential candidate Joe Lieberman, reveal his intentions to assert a new political influence. And if he can maintain his wide range of influence while altering his rogue image, Farrakhan could become an important power broker. However, some black analysts note the Nation of Islam has more in common with the religious right than with the liberal left that traditionally has allied with African-Americans. "Although I applaud his move away from narrow nationalism, I'm still skeptical of his politics," says Barbara Ransby of the University of Illinois in Chicago, who is one of the founders of the Black Radical Congress and consistently has provided a radical critique of Farrakhan's militant conservatism. "He seems firmly wedded to a conservative and patriarchal view of the family and I would prefer that message to have a smaller rather than broader audience." Farrakhan may well confound his critics by adopting a model of progressive politics that is characteristic of left-leaning religious groups. In fact, the "National Agenda" that accompanied his Million Family March is a rather curious mixture of progressive and conservative policy prescriptions. Consider the agenda's "Declaration of Family Bill of Rights and Responsibility," which includes the following: "All families have a right to a livable income to attain and maintain decent shelter, food, clothes, exposure to the arts and cultural integrity but also the responsibility to seek self-help, self-determination and shared responsibility for eliminating poverty and economic inequities." Or this: "All families have a right to be free from inequities and discrimination based on immigration status, race, ethnicity, gender, age, and religion but also the responsibility to internally and externally resist prejudice and bigotry." If nothing else, we are witnessing the evolution of one of the

African-American community's most durable groups. It remains the

most disciplined black group in the country. Whatever happens to

the Nation of Islam, there is no doubt the rest of us eventually

will feel the impact. Whether that impact will be positive or negative

depends almost solely on the skills of Farrakhan.

|