|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

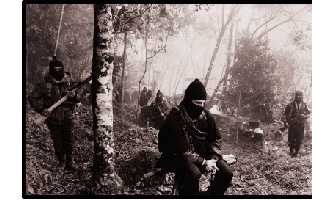

In the breathless solitude of the first years of the Zapatista uprising, a peculiar fellow appeared at our camp; a little smoking beetle, very well read and an ever better talker, who gave himself the task of giving his company to a soldier, El Sup. Legally named Nebuchadnezzar, this beetle, traveling incognito, goes under the nom de guerre Durito, because of his hard shell. ... Mexico City. Durito wanders through the streets adjoining the Zocalo. Sporting a

"This city is sick," Durito writes to me. "It is sick from loneliness and fear. It is a great collective of solitudes. It is a collection of cities, one for each resident. It's not about sums of anguish (do you know of a loneliness without anguish?), but about a potency; each loneliness is multiplied by the number of lonely people that surround it. It is as though each person's solitude entered a House of Mirrors, like those you see in the country fairs. Each solitude is a mirror that reflects another solitude, and like a mirror, bounces off more solitudes." Durito has begun to discover that he is in foreign territory, that the city is not his place. In his heart and in this dawn, Durito packs his bag. He walks this road as though taking inventory, a last caress, like a lover who knows this is good-bye. At certain moments, the sound of footsteps diminishes and the cry of the sirens, which frightens outsiders, increases. And Durito is one of those outsiders, so he stops on the corner each time the red-and-blue blinking lights crisscross the street. Durito takes advantage of the complicity of a doorway in order to light a pipe guerrilla-style: a tiny spark, a deep breath, and the smoke engulfing his gaze and face. Durito stops. He looks and sees. In front of him, a display window catches his eye. Durito comes near and looks through the great glass pane to what exists beyond it. Mirrors of all shapes and sizes, porcelain and glass figurines, cut crystal, tiny music boxes. "These are no talking boxes," Durito says to himself, without forgetting the long years spent in the jungle of the Mexican Southeast. Durito has come to say good-bye to Mexico City and has decided to give a gift to this city, about which everyone complains and no one abandons. A gift. This is Durito, a beetle of the Lacandon Jungle in the center of Mexico City. Durito says good-bye with a gift. He makes an elegant magician's gesture. Everything stops. The lights go out like a candle extinguished by a gentle lick of wind on its face. Another gesture and a reflecting light illuminates a music box in the display window. A ballerina in a fine lilac costume holds an endless stillness, hands crossed overhead, legs held together, balanced on tiptoes. Durito tries to imitate the position, but promptly gets his many arms entangled. Another magic gesture, and a piano, the size of a cigarette box, appears. Durito sits in front of the piano and puts a jug of beer on top--who knows where he got it from, but it's already half empty. He cracks and flexes his fingers, doing digital gymnastics just like the pianists in the movies. Then he turns toward the ballerina and nods his head. The ballerina begins to stir and makes a bow. Durito hums an unknown tune, beats a rhythm with his little legs, closes his eyes. The first notes begin. Durito plays the piano with four hands. On the other side of the glass pane, the ballerina begins to twirl and gently lifts her right thigh. Durito leans on the keyboard and plays furiously. The ballerina performs her best steps within the prison of the little music box. The city disappears. There is nothing but Durito at his piano and the ballerina in her music box. Durito plays, and the ballerina dances. The city is surprised; its cheeks blush as when one receives an unexpected gift, a pleasant surprise, good news. Durito gives his best gift: an unbreakable and eternal mirror, a good-bye that is harmless, that heals, that cleanses. The spectacle lasts only a few instants. The last notes fade as the cities that populate this city take shape again. The ballerina returns to her uncomfortable immobility; Durito turns up the collar of his trench coat and makes a slight bow toward the display window. "Will you always be behind the glass pane?" Durito asks her, and asks himself. "Will you always be on the other side of my over here, and will I always be on this side of your over there?" Durito crosses the street, arranges his hat and continues to walk. Before going around the corner, he turns toward the display window: He notices a star-shaped hole in the glass. The alarms are ringing uselessly. Behind the window, the ballerina is no longer in the music box. • • • "This city is sick," Durito writes to me. "When its illness becomes a crisis, it will be cured. This collective loneliness, multiplied by millions and empowered, will end by finding itself and finding the reason for its powerlessness. Then, and only then, will this city shed its gray dress and adorn itself with brightly colored ribbons, which are so abundant in the provinces. "This city lives a cruel game of mirrors, but the game of the mirrors is useless and sterile if finding the transparency of glass is not a goal. It is enough to understand this and, as who-knows-who said, struggle and begin to be happy. "I'm coming back. Prepare the tobacco and the insomnia. I have

a lot to tell you, Sancho." Durito signs off. Adapted from Our Word Is Our Weapon, selected writings of Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, recently published by Seven Stories Press.

|