|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

With Republicans controlling the presidency and both houses of Congress for the first time since 1952, it might seem to be a gloomy moment for progressive Democrats and their allies in the labor, environmental, civil rights and other movements. But there is a surprisingly strong sentiment that, besides playing defense, progressives could score some political gains in the next few years. There are several reasons for cautious optimism. Bush enters office as a weak, wounded president, and Republican congressional control is very slim, subject to Democratic filibuster in the Senate. To win, Bush campaigned as a Clinton Republican, promising progress on health care, education and other traditional Democratic issues. Given that the majority of voters supported Gore or Nader, and the even stronger majorities supporting progressive views on major social and economic issues, if there is any mandate at all from the voters, it is not for what has been the Republican agenda. Bush will be under strong pressure to prove that he is a conciliator who can get things

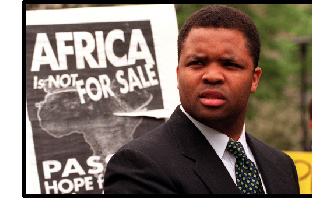

Progressives differ on whether they think that much will be accomplished legislatively, but they agree the best way for progressives to block Bush, as well as to lay the groundwork for future political victories, is to promote their issues clearly and aggressively, appealing to a sympathetic public. "This election made clear the country doesn't want a tax cut for the wealthy or to dismantle health care or Social Security," says AFL-CIO public policy director David Smith. "Of course, we will fight to hold the line on these issues, but it would be an enormous mistake for progressives to think that diving into the bunker is our only option. We also have to press ahead on issues that the country cares about, especially health care. I think we have room to make some progress." Part of the battle will be defining what constitutes progress or getting things done. "There will be an effort to pick off some Democrats," says Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Illinois), a rising progressive leader in the House. "If we let them define bipartisanship as a couple of Democrats going their way, then shame on us. It's our role to prevent that kind of rightward drift and make it clear in every forum, including Democratic caucuses, to remind people who the Democratic base is and who created this popular victory for Gore." There's strong sentiment on the Democratic left that the party needs to define itself more clearly in terms of its fundamental values and philosophy, not just in terms of specific legislative proposals or tactical positions to gain political advantage over the Republicans. If Democrats stand for principles that people understand and support, then some strategists think that they cannot only better block unpalatable compromises with the Republican right, but ultimately secure a stronger political position for future elections. Yet this requires winning over or resisting conservatives in the party, from the "blue dog" faction in Congress to the Democratic Leadership Council. "The Democrats really need to be organized and have a coherent plan that we can get people to unite behind, and that ought to be our focus," says Rep. Dennis Kucinich (D-Ohio), the new leader of the Progressive Caucus. "It has to be forward-looking and positive. It would be a mistake to lead a frontal assault on Bush now. The real question is what do we stand for as the Democratic Party. It's not just unity. There needs to be a lot of time and attention paid to re-examining the philosophical basis of our party and to define the social, economic and political pillars of the party." Kucinich says the debate in Congress recently has been "more about tactics than philosophy" on both sides, but "the answer to rank partisanship is not a pantomime over bipartisanship." Although he believes it's possible to find unity, some of the positions he is currently proposing for the party--such as opposition to national missile defense and nuclear disarmament-- will find strong opposition on both sides of the aisle. Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr. (D-Illinois) wants to reorient politics to a debate over

Progressives are intent on staking out positions that make it difficult for Bush to muddy the differences on key issues, as he did so successfully with education, a patient's bill of rights, prescription drug coverage for seniors and other issues during the election. If Democrats make the defining issue universal access to health care, Schakowsky says, it will be harder for Bush to persuade people that Democrats and Republicans are indistinguishable. But Service Employees Union President Andrew Stern, who represents many health care workers, says it may be possible to pass a significant expansion of access to health care short of universal coverage, partly because there's a growing bipartisan view that work should offer more benefits--including health insurance--and both parties promised to use the surplus to expand health care. "We should focus on trying to win for our members and not worry about 2002," Stern says. Early battles may set the tone. If Sens. John McCain (R-Arizona) and Russ Feingold (D-Wisconsin) push through their campaign finance legislation, as they believe they can, then Bush will immediately be put on the defensive. But if Bush can push issues that were blocked only by a Clinton veto or veto threat, such as abolition of the estate tax, then Democrats risk being deeply divided over an issue that could otherwise be used to demonstrate how Bush is promoting policies that unfairly help the super-rich. If a recession hits, Bush has already made it clear that he will use traditional Keynesian arguments to rationalize his proposed $1.3 trillion tax cut. The progressive alternative should be public investment both as a stimulus to the economy and to do needed work, but the Democrats are ill-positioned for that argument after years of claiming to be champion budget-balancers. "This is the Democrats' most important vulnerability," argues Jeff Faux, president of the Economic Policy Institute. "They have become so unused to arguing for social investment. It will be very difficult if the unemployment rate starts to rise very significantly, and all they can talk about is maintaining the surplus for Social Security in 2035. That's where Clinton and Gore led them. There will be great pressure to find the lowest common denominator between the New Democrats and progressives." Ironically, with Clinton out of the White House, progressives may be better positioned to resist fast-track trade negotiating authority and to demand that global economic agreements protect the environment and workers rights. Democrats who were loyal to the White House now may be free to vote for a position that has wide popular support. (Indeed, one even Clinton had started to embrace at the end of his term, when the administration negotiated a bilateral trade agreement with Jordan that included labor and environmental protections.) Progressives will have virtually no influence on administrative appointments and executive actions that Bush can take. Under the circumstances, this is where the administration may do its greatest early damage, stalling or reversing decisions made late in the Clinton administration to protect the environment or set ergonomic standards for workplaces. Clinton managed to make some progress despite a Republican Congress through administrative guidelines, such as one just issued that would permit the federal government to bar contractors that repeatedly violate labor, environmental and other laws. Bush can favor corporations in much the same way. "In the area of legislation, we can hold our own to an extent because of the lack of a mandate for Bush and the numbers of Democrats in the House and Senate," argues AFSCME President Gerald McEntee. "But of real concern is the power of the executive branch, whether in Health and Human Services, Education or other departments. The president can write regulations and put into effect executive orders and make appointments. The people who do the day-to-day business that people so often don't see can have a lot of effect." The key to any progressive strategy will be the ability to mobilize citizen pressure on Congress, including the Democrats. Within the Beltway, the pressures on Democratic leaders will be for compromise and bipartisanship. "That's why we've got to not let these folks, good as they are, to set the tone for us," argues Stewart Acuff, assistant Midwest regional director of the AFL-CIO. "We have to organize around what people need and want and what's just, instead of organizing around what--as much as I love them--Dick Gephardt, David Bonior or Tom Daschle think is viable." While Sierra Club executive director Carl Pope sees little hope for environmentalists under a Bush administration, he says that it's crucial to change politics over the next few years so that citizens will vote more on their environmental and economic concerns and less on cultural issues. In the short run, he expects tough defensive fights, especially over Bush's proposal to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas exploration. Yet for both the short and long run, he says, "I never count on leadership from politicians. The public will have to lead on this." Some members of Congress will welcome such popular pressure, since it can strengthen their hand. Schakowsky thinks Democrats can only make headway by "building the progressive infrastructure and making the progressive voice louder," strengthening their own institutions in Congress and supportive citizens' groups like U.S. Action. "One thing Democrats have not fully taken advantage of is the opportunity to utilize and foster creation of grassroots supporters," she says. "They've played too much of an inside-the-Beltway strategy." As a result of the way Bush won this election, there's a reservoir

of anger, especially in the black community and in union circles,

and there is the potential for more popular discontent as the limits

of Bush's compassionate conservatism are revealed. If groups on

the left can mobilize supporters, and progressive Democrats in Congress

can keep their fractious party united around issues that are both

popular and populist, then the battle with the Bush administration

could lay the groundwork for decisive progressive political--and

eventually legislative and electoral--victories in the coming years.

|