|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The Nature of Generosity William Kittredge grew up in the first half of the last century in the Warner Valley of southeastern Oregon, a place of great cultural isolation where, he writes, "The way in was the way out. Sagebrush deserts on the high and mostly waterless plateaus to the east were traced with wagon-track roads over rimrocks and salt-grass playas from spring to spring, water hole to water hole, but nobody ever headed in that direction with an idea of the future." Kittredge's friend and longtime colleague in the creative writing department at the University of Montana, the poet Richard Hugo, once wrote in an essay: "Given our lean cultural holdings we grabbed at almost anything that offered escape or amusement." For Kittredge that meant books. He became a classic autodidact. Even when he was looking after his family's ranch in his twenties and thirties, he would wake each day at 4:30 a.m. and put in an hour with a book before heading out to breakfast with the men who worked for him. It was a beautiful life for awhile, something near paradise. He lived in age-old intimacy

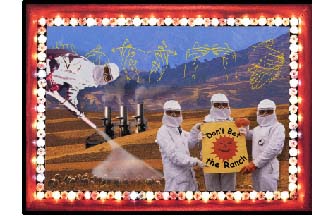

In Hole in the Sky, a fine memoir written before the current fixation with the genre, he put it this way: Over something like three decades, my family played out the entire melodrama of the nineteenth-century European novel. It was another real-life run of that masterplot which drives so many histories, domination of loved ones through a mixture of power and affection; it is the story of ruling-class decadence ... that we reenact over and over, our worst bad habit and our prime source of our sadness about our society. We want to own everything, and we demand love. We are like children; we are spoiled and throw tantrums. Our wreckage is everywhere. Coming to terms with that wreckage, for Kittredge, is serious business. But he also has a knack for seeing to the heart of things with a wry sense of humor. "A Redneck pounding a hippie in a dark barroom is embarrassing because we see the cowardice," he wrote in Owning It All. "What he wants to hit is a banker in broad daylight." In his books, Kittredge has fashioned a highly personal and sophisticated reckoning with the mythic story of the American West. Far from merely charting the damage, he seems intent on altering the very vocabulary of his culture. Certain words and phrases appear repeatedly in his work: "complexity," "actual," "healing," "cherish," "taking care." His tale is a cautionary one; his project, in essence, is the naming of those things he has come, through hard-won experience, to value. "We are what we can say or sing," he writes in The Nature of Generosity, his most ambitious book to date. Composed as a kind of montage, it moves across memories of his entire life, ruminations on his visits to Venice and Machu Picchu and the caves at Lascaux, and references to perhaps a hundred of the books he has read and been moved by. Part travelogue, part armchair philosophy, it's an exercise in what might be called anthropology of the self. For instance, he quotes Simone Weil's "The Iliad, or the Poem of Force": "To define force--it is the X that turns anybody who is subject to it into a thing. The hero becomes a thing dragged behind a chariot in the dust." He then recalls reading The Iliad as a young man and tries to see his family's story through the dual prisms of Weil and Homer. "The pleasures of reshaping the world had led to betrayal and blood," he writes. "And families, hired hands, livestock, waterbirds in great flights on a summer morning--they also become things dragged in the dust behind the chariot of our ambition to own the world." Through a sophisticated juxtaposition of scene and quotation, memory and dream, he advocates what he calls "extreme long-loop altruism," or "generosity toward strangers and ways of life we never expect to encounter as a method of preserving both biological and cultural multiplicity." Kittredge elsewhere has said that for many years he had little use for politics. Even after escaping the ranch and beginning a new life as a writer and teacher, he understood storytelling as the main endeavor and politics as a dirty, far-off, unconnected business. But he has come to believe that storytelling is politics, insofar as stories help us name what we consider invaluable. In The Nature of Generosity, he finds people spinning narratives of hopefulness, in ways both practical and philosophical. A neighbor in Missoula, Doug Bleecker, has transformed an untillable former junkyard into an intricate garden by planting peppers, beans and tomatoes in upturned steel drums filled with soil. "Ripening cantaloupe were suspended high above the ground in old bras donated by women friends, and blossoming flowers, including seventy-five varieties of tulips, were interplanted with vegetables in abandoned urinals and bathtubs." At the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, he listens to a theologian named John Cobb, who believes Europeans are entering a fourth societal revolution. First came Christianity, then nationalism, then a widespread belief in capitalism and economic growth as "a source of worldwide economic coherence." Now, Cobb says, we're entering a period where "earthism" will become the dominant ideology, one that puts each of us at the center of a project of caretaking for the planet and one another. This will come none too soon. As Kittredge points out--to choose just one example of the forces arrayed against such a project--industrial agriculture is precipitating an economic and ecological crisis. Major food conglomerates now control almost every stage of the production process, from the patented (and genetically altered) seeds that grow crops to the finished product on the shelf. They've justified this in the name of efficiency, yet "the miseries of starving people around the world are to a great extent the result of inhumane choices within the market system, while agricultural corporations pretend this is the very tragedy they mean to prevent." Here, for the first time, Kittredge writes very briefly about his other career, teaching. He says that, for one assignment, he asked his students to drive the commercial strip in Missoula, scrutinizing billboards and listening to commercial radio. "Their job was to count the number of times they thought they'd been lied to and tell me what it meant to them. Most hated the assignment, and I couldn't blame them. What comfort is found in the idea that we're incessantly tricked by powerful entities?" This illustrates what Kittredge does best in his writing, too, forcing us to see the world through fresh eyes. But the places here where he slips into a preacher's robe are the least satisfying; he achieves his most powerful effects through juxtaposition, not polemic. There's a lovely scene in the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Venice, where he stands before several Byzantine mosaics of Christ and the apostles: These stern images demanded that I inhabit emotions they didn't cause me to feel. Hard-edged and formal, they were news from a world that I had never inhabited, so they remained, for me, a set of vivid abstractions. Make of us, they said, what you can. But they were news from someone else's reconciliation with death, designed to honor a deity who seemed mostly oppressive and thus emotionally useless to me. So most of my time was spent at the other end of the cathedral, studying a twelfth-century mosaic depicting the Last Judgment ... which brought me to emotions more useful than dread. Everything depicted there descended through Eve's flowing golden hair, a cascade of significance reaching downward from Christ's crucifixion to human dead yielded up from the burying earth and the digestion of animals and sea creatures, the elect and the damned, their souls attended to and placed in balance. This, I felt, is how things actually are, interconnected by a fragile living tissue. At heart, Kittredge is an optimist. He believes we have it in us

to shape a future where munificence without coercion becomes our

defining impulse. He made his escape from oppressive social structures.

Why can't all of us? "Generosity is the endless project," he believes,

and this lyrical work points the way. Philip Connors is editor of the literary magazine Croonenberghs' Fly, whose first issue will be published this spring.

|