|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The early reviews are in on the new George W. Bush administration. It has all the elements of the classic horror story: a predictable plot, familiar villains and an unshakable sense of déjà vu. On the following pages, we take a look at Bush's nominees and appointments, a diverse cast of characters in every way but ideology. Left to their own devices, this collection of unrepentant cold warriors, anti-choice extremists, Wise-Use desperados and corporate shills (as well as a couple of reasonable old-fashioned conservatives) could make for a harrowing next four years. Can the forces of good thwart this evil plan? Well, as In These Times went to press, thousands of townspeople were taking their torches to Washington to protest Dubya's inauguration, making one thing clear: There will be no honeymoon! Craig Aaron

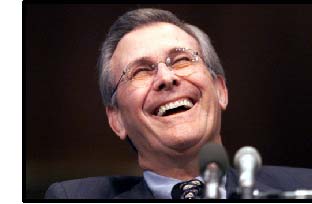

Toward the end of his January 11 confirmation hearing, Donald Rumsfeld, George W. Bush's designated secretary of defense, fielded a pointed query from Sen. Robert Byrd. The West Virginia Democrat noted that Pentagon auditors had discovered that a whopping $2.3 trillion in Defense Department financial transactions couldn't be accounted for in the past fiscal year. "My question to you, Mr. Secretary," Byrd intoned, "is what do you plan to do about this?" "Decline the nomination," Rumsfeld deadpanned, defusing the tension by provoking a round of bipartisan laughter. It's too bad he was joking. While John Ashcroft has become the über-conservative lightning rod of the Bush transition, Rumsfeld--who's just as frighteningly right-wing as the Missouri Pentecostal, though in more esoteric ways--has avoided almost any storminess entirely. Long referred to as "Rummy" by friends and colleagues, the appellation is indeed an

through shrewd private subversion and hardball public politicking--the promotion of an extremist agenda hostile to virtually any arms control agreement. Regarding nuclear disarmament as something akin to particularly resilient undead bloodsucker, Rummy the Vampire Slayer's first confirmed kill came in 1975. Then in the midst of negotiating the second Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties (SALT II) with the Soviet Union, Henry Kissinger had planned to visit Moscow after completing an Asian swing in the hopes of wrapping up the negotiations. Between Hong Kong and Jakarta, Rumsfeld (then in his first incarnation as secretary of defense, under Gerald Ford) cabled Kissinger with piquant objections that forced him to reluctantly call off his trip. Then with Kissinger still in the field, right-wing establishment columnists Evans and Novak reported that a number of Ford advisers were "outraged" at Kissinger's "drafting top secret proposals for major concessions to Moscow." The only hope to save the Republic from the betrayal of giving away the nuclear farm: Donald Rumsfeld, of course. Though the sources for the Evans and Novak column were anonymous, those in the know had little trouble identifying them. A small coterie of conservative arms control opponents in the executive and legislative branches was becoming increasingly, if quietly, effective, and to them--Senate aide Richard Perle, Arms Control and Disarmament Agency deputy director John Lehman and Lt. Gen. Edward Rowny, among others---Rumsfeld was an ally, the antithesis of Kissinger, whose ideas of "détente" and "rapproachment" were not in line with their notion of "peace through strength." Indeed, to this clique and their fellow travelers, no less an organization than the CIA was complicit in weakening America's defenses. According to them, agency analysts had been underestimating the strength of the Soviet nuclear arsenal for years, thus leading to dangerously low American defense expenditures. Many of Rumsfeld's protégés became the now infamous "Team B," the group of "outside experts" who not only wildly spun the CIA's existing data to reflect their own doom-and-gloom views, but mounted an effective media campaign of leaking and spinning to create something approaching public hysteria. They effectively undermined the incoming Carter Administration's disarmament efforts and laid the foundation for the explosion of the defense budget in the Reagan years. Though Rumsfeld entered the private sector after the Ford administration, virtually all of his protégés and comrades were elevated to positions of power under Reagan. From there, they defended programs Rumsfeld had pushed, like the MX missile and B-1 bomber. Though he did a brief turn as a special envoy to the Middle East in 1983-1984, the Rummy also played a quiet and influential role as adviser to Eugene Rostow, head of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA). When Reagan fired Rostow in 1983, the president replaced him with another of Rumsfeld's protˇgˇs: Ken Adelman, whose sum total defense experience had been one year as Rumsfeld's special assistant at the Pentagon. Not surprisingly, Rumsfeld continued on as a member of ACDA's advisory board. In the past decade, Rumsfeld's name usually has appeared on letters opposing various forms of arms control, including the chemical weapons ban. But it's only recently that Rumsfeld truly has reasserted himself as a patron saint of the Star Wars lobby. In 1996, Rumsfeld occupied a pivotal position as Bob Dole's defense adviser. Thus, according to Dole, America's "top defense priority" became National Missile Defense, a scaled-down version of the grand Strategic Defense Initiative of the Reagan days. There was, however, a problem with Dole's assertion: Intelligence data and analysis didn't bear out the necessity of rapid NMD deployment. In 1995, the CIA reported that a nuclear missile threat from a new foreign power to the United States was at least 15 years off, and that the costly missile defense experiments were at best dubious. At this point another Rumsfeld acolyte, Frank Gaffney Jr. of the Center for Security Policy, mounted a campaign against the CIA's estimates and, with the aid of right-wing Republicans in Congress, successfully pushed for an alternative, outside assessment--in effect, another Team B. This time, however, the team--headed by ex-CIA Director Robert Gates--essentially concurred with the CIA. Once again, Gaffney called for another review. Thus the Commission to Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States was formed, with Donald Rumsfeld as its chairman. Widely characterized as "bipartisan in its conclusions," the final Rumsfeld Commission report declared that the CIA was wrong and the very real threat of ICBM attack from a "rogue state" was at most five years away. Such an event, Rumsfeld said, could occur with "little or no warning." Scores of experts since have taken issue with the report's analysis, noting that key variables and scenarios were ignored or unexamined by the commission. While the report didn't explicitly recommend the deployment of NMD, there was no doubt as to Rumsfeld's desire to see the system--which Clinton had vetoed--put back into play, which is exactly what happened. For NMD to become a reality, however, would require amending the landmark Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty--something the Russians aren't too keen on doing. No matter, Rumsfeld says. True to form, at his confirmation hearings, the Rummy dismissed the ABM treaty as "ancient history." Rumsfeld's reappointment to the Pentagon also portends the probable

return to power of Reagan-era defense bureaucrats. Dismissive of

the idea of a world community and the evolving problems it faces,

Rumsfeld and his ilk will likely try to recast the global power

dynamic as the one they're more familiar with: a world of nuclear

superpower polarity, where the guy who controls the balance of terror

with the biggest nuclear arsenal wins.

|