|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

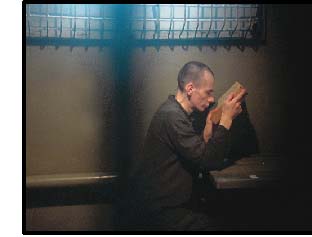

Sweeping amendments to Russia's criminal code are about to trigger the biggest mass release of prisoners since the Stalin-era Gulag camps were emptied during the political thaw of the '50s. Experts worry that many of the estimated 350,000 convicts who will soon hit the streets of Russian cities may be homeless, alcoholic, drug-addicted or infected with AIDS or tuberculosis. But even critics concede the new law, which parliament is expected to pass within months, signals the first-ever serious attempt to clean up Russia's overcrowded, noisome and brutality-plagued prisons, which presently hold more than a million inmates. The law's proposed limits on pretrial detention, reduced sentences for petty crimes and expansion of the probation system will make up to one-third of prisoners eligible for swift release. "It is only half a step forward, but it will partially relieve some of the ugliest problems," says Major General Sergei Vitsin, one of Russia's leading criminologists and an adviser to both the Kremlin and the Helsinki Group, a Russian human rights movement. "Our state is being pushed into this reform for urgent financial reasons, but the logic leads in a progressive direction." More than 20 million Russians have passed through the prison system, one of the

One-in-10 Russian prisoners is infected with tuberculosis, many with a drug-resistant strain of the disease that is almost impossible to treat. Experts warn that AIDS is rife in the jail system, and is spreading due to the rapid growth of heroin addiction. It is hoped that the new law will dramatically ease the situation. In the short run, the expected prisoner exodus will reduce overcrowding and enable the state to improve nutrition, health care and living conditions for the remaining inmates. But an amnesty of 120,000 convicts last year proved insufficient. "An amnesty is a one-time measure that lets off steam but does not address the underlying problems of our system," says Oleg Filimonov, deputy chief of Russia's department of corrections and the main author of the new law. "We need sustained reforms that will make our prisons more humane and fair, as well as more efficient."

|