|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The early reviews are in on the new George W. Bush administration. It has all the elements of the classic horror story: a predictable plot, familiar villains and an unshakable sense of déjà vu. On the following pages, we take a look at Bush's nominees and appointments, a diverse cast of characters in every way but ideology. Left to their own devices, this collection of unrepentant cold warriors, anti-choice extremists, Wise-Use desperados and corporate shills (as well as a couple of reasonable old-fashioned conservatives) could make for a harrowing next four years. Can the forces of good thwart this evil plan? Well, as In These Times went to press, thousands of townspeople were taking their torches to Washington to protest Dubya's inauguration, making one thing clear: There will be no honeymoon! Craig Aaron

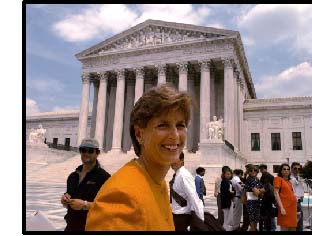

Since New Jersey Gov. Christie Todd Whitman was tapped by George W. Bush to head the Environmental Protection Agency, she has been given a free pass by everyone but the environmental and community activists in her own home state, who are familiar with her history of hiding a conservative, business-led agenda under a "moderate" label. Whitman took office in 1994, proclaiming New Jersey was "open for business,"

Not surprisingly, the type of aggressive enforcement feared by polluters has largely disappeared in the Garden State. Since Whitman became governor, fines issued to industries, sewage plants and other facilities that discharge pollution into waterways have dropped 70 percent. On-site toxic releases by companies have increased by 20 percent, while the number of facilities has declined. However, Whitman has worked hard to burnish her outdoorsy image. She has kissed animals, canoed streams, clapped at horse shows, and hiked and biked in photo-ops from Bergen County to Cape May. But it is widely acknowledged by environmentalists that her shifting of resources from pollution prevention to public relations has caused immeasurable harm. Also troubling has been her lack of serious commitment to the environmental health of workers in toxic industries and to the state's poorest communities, which are often located in the shadow of oil refineries, chemical plants and other industrial facilities. In 1995, an explosion at a chemical plant in Lodi, New Jersey killed five workers, injured many others and reduced the facility to rubble. After burying their co-workers, about 30 survivors asked to meet with Whitman to discuss, among other issues, her removal of 2,000 chemicals (including those that caused the Lodi explosion) from a list of hazardous substances used to help guide emergency workers and to inform workers and residents of potential hazards. They also wanted to discuss a public statement she made blaming workers for the tragedy. Subsequent investigations by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the U.S. Chemical Safety Board found the company management at fault. But Whitman, blaming her "hectic schedule," couldn't find one hour to meet with workers. More recently, Whitman cut the ribbon on construction of a cement factory in one of the nation's poorest neighborhoods, Waterfront South in Camden. The St. Lawrence Cement Co., which will employ 15 workers, was built without significant input from residents, despite a state policy that calls for "fair and equitable treatment" of such communities. When the plant opens later this year, residents fear dust particles from the grinding of limestone slag--combined with diesel exhaust from trucks--will exacerbate already acute health problems in the community, where more than 60 percent of its mostly African-American residents already report respiratory health ailments. (Whitman is also under fire for her role in the racial profiling of motorists. Particularly disturbing is a 1996 photograph showing her frisking an African-American suspect during a ride-along tour with police in Camden.) Whitman's record in New Jersey shows that her brand

of corporate environmentalism, characterized by the bait-and-switch

tactic of spinning her green image while quietly allowing polluters

to police themselves, may be just as damaging to the environment

as that of a more overtly ideological nominee. It will certainly

be more insidious. Indeed, it will be no surprise if Whitman interferes

with scientific findings, undermines anti-pollution enforcement

efforts, does little to discourage the building of hazardous facilities

in poor communities--all while rafting down the Colorado River and

smiling for photographers. Jim Young writes about labor and the environment and is special projects director for the New Jersey Work Environment Council, a labor and environmental coalition based in Lawrenceville.

|