|

Where's Ralph? That's what many enthusiastic supporters of Nader's

2000 presidential campaign have been asking. Even though more people

were paying attention to politics during the Florida election mess

than they were during the campaign, Nader chose not to go to the

Sunshine State. Nor has there been a coordinated effort to mobilize

the tens of thousands of active Naderites recruited during the campaign

to take their energy into the Green Party, let alone any serious

attempt to enroll rank-and-file Nader voters as Greens. Indeed,

Nader himself is still not a Green Party member. Nor has any organization

been formed to give those Nader supporters who are not prepared

to join the Greens another vehicle for independent, issues- oriented

political action. So what's going on?

Ask Nader, and he maintains he has been doing a lot. "It's very

hard to get press attention, much more so than in the campaign,"

he says. Undoubtedly true--but Nader gave no press conferences of

his own in December or January, and sent out only two press releases;

nor did he stage any media events with pizzazz.

And what about Florida? "Medea Benjamin represented the Greens

in Florida," he

|

|

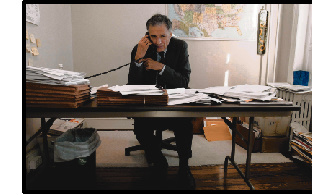

"Wait for spring, the

time of rebirth," Nader says.

JOYCE NALTCHAYAN/AFP

|

says, "and she did a great job." But the Green Senate candidate from

California garnered no national media attention of the kind Nader

might have, given the thousands of hours of airtime the cable news

networks devoted to the endless squabbling over the vote count.

As for the Greens, Nader says he hasn't become a member because,

"I don't want to get involved in Green Party internal disputes and

struggles--if I was a member, I'd have to take sides." Besides,

adds Nader--who has made it evident he almost certainly intends

to run another presidential campaign in 2004--"we've got to appeal

to the independent vote" that includes "tens of millions" whose

concerns extend beyond the Greens' agenda "and historically, I've

never joined any party."

As to his invisibility during the confirmation hearings for Bush's

cabinet, Nader says the Democrats shut him out: "I sent letters

to [Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick] Leahy--we even

had one hand-delivered--asking to testify against John Ashcroft,

and he didn't even have the courtesy to respond." He also tried

to testify against Spencer Abraham and Gale Norton, but was refused.

Why, then, didn't Nader hold a press conference denouncing the

spineless Senate Dems for their token opposition to Ashcroft--who

lied repeatedly without challenge at his hearing--and their failure

to seriously contest the anti-environmental appointments of the

reactionary Norton and the polluter-friendly new EPA head, Christie

Todd Whitman? And when the Democrats symbolized their moral bankruptcy

by choosing notorious bagman and fixer Terry McAuliffe as chair

of the Democratic National Committee, where were the salvos from

Nader? "Well," he says weakly, "I've done a lot of all this on radio."

Nader repeatedly emphasizes how preoccupied he has been trying

to comply with the Federal Election Commission regulations governing

campaign spending and the transition out of campaign mode, including

restrictions on how campaign staff can be deployed to other activities.

(Nader's Washington campaign office is still open, but down to a

skeleton staff.) "The FEC-dictated process is very strict and very

complicated," Nader notes, adding, "did you know that it costs $5,000

a month just to rent the software for FEC compliance?"

But as one who publicly supported Nader's candidacy in 2000 (including

in these pages) and his symbolic non-campaign of 1996, I feel compelled

to be frank: These excuses sound to anyone steeped in politics like

"the FEC ate my homework." Clearly, there's more to Nader's absence

from the public scene than he's willing to admit.

After discussions with a number of Nader's closest advisers, friends

and staff, a clearer picture emerges. For one thing, Nader has received

conflicting counsel. Some of the influential staffers from the Nader-created

skein of nonprofits, particularly Public Citizen, have been reluctant

to see Nader conduct a frontal assault on the Democrats just before

a congressional election year.

But while the conventional wisdom holds that the first off-year

election is always good for the party out of power in the White

House, 2002 does not appear to be a banner year for the Democrats.

They will likely lose at least three Senate incumbents: Louisiana's

Mary Landrieu, South Dakota's Timothy Johnson and Montana's Max

Baucus. Georgia's Max Cleland, Iowa's Tom Harkin and even New Jersey's

Robert Torricelli could all have tough races as well. In contrast,

unless the ailing Jesse Helms retires or the senile Strom Thurmond

drops dead in midterm, most of the Republican senators up next year

are pretty safe, with the best chance of a Democratic pick-up in

New Hampshire, where Gov. Jean Shaheen will run for lunatic blowhard

Bob Smith's seat.

Things aren't much better in the House, since Republicans control

nearly two-thirds of the statehouses and dominate the legislatures

in half of the states, which must draw new district lines in the

wake of the 2000 census. The National Committee for an Effective

Congress (the nation's oldest and most effective liberal political

action committee) has been working flat-out on the state-by-state

redistricting process for months. Says the group's veteran director

Russ Hemenway of the battle for the House: "When all the new lines

are drawn and depending on how the courts eventually decide expected

challenges, in the end the Democrats will do no better than break

even or lose up to 20 seats."

Even though it ought to be clear to anyone with half a brain that

Al Gore blew his chances with his smarmy, inconsistent flip-flopping--failing

to carry either his home state of Tennessee or Clinton's native

Arkansas, for example--some non-Green Naderites worry that an all-out

attack on the Democrats now would only magnify Nader's image with

some liberals as a "spoiler." As one senior Nader strategist puts

it: "Most of the enviros are mad at Ralph--some people didn't want

him to rub salt in their wounds."

Moreover, Nader habitually has a long gestation period (witness

the crippling late start to his 2000 campaign, which sent out its

first direct-mail fundraising letter so tardily that returns didn't

start to come in until last July). "Ralph always plays his cards

close to the vest," says one key adviser. "And after a tough, rigorous

campaign, he needed recuperation time--he is, after all, 66."

There's also the major problem of how to approach and deal with

the Greens, with whom Nader has had a sometimes-prickly relationship.

Local Green parties vary tremendously from state to state. The culture

of the Greens is still heavily impregnated with what one might call

a politically vegan disdain for electoral politics. And in some

states the leaders from this mindset are reluctant to turn over

the party apparatus to the scads of freshly minted Nader campaign

cadres from 2000, regardless of their enthusiasm, energy and skills.

The Greens need to decide whether they want to become a truly alternative

electoral force, one that could in many places decide the balance

of power and help discipline the Democrats into abandoning their

money-dominated drift into corporate centrism, and thus begin the

process of realigning American politics to the left.

Especially with Jesse Jackson's co-optation by the Clinton White

House and the Gore campaign, his cozying up to Wall Street, and

his self-destruction by using Rainbow/PUSH funds to pay off his

pregnant mistress, Nader is still the most visible and valuable

asset of the real left (as opposed to the "left" in the debased,

Crossfire sense of the term). And there's a real danger that

well-meaning liberals will, in the wake of the Florida debacle,

skew the national debate to one about process (electronic scanners

versus chads, weekend and computer voting, and the like) rather

than the more fundamental one about power--the corrupting influence

of wealth and corporate control of governance, a systemic critique

that Nader is uniquely positioned to make and which was the groundbreaking

hallmark of his national campaign.

To galvanize an organization, one top Naderite told me, "there

either has to be an issue or the recruitment of credible and attractive

Green candidates around whom people can be mobilized." Another Nader

adviser says, "Ralph really has only two choices: shut up or build

the Green Party."

At this point, it's obvious that Nader has not yet firmly fixed

his course. "I've been trying to encourage the Green Party to establish

a national presence, a lobbying office, here in Washington," Nader

says, "and to help recruit hundreds of candidates in 2002--we had

over 260 in 2000, and we want over 1,000 in 2002." He adds: "The

students have prepared an initiative to establish 900 campus Green

chapters--we had 900 campus coordinators last year. I've been on

six or seven campuses since the campaign--there's lots of energy--it's

like the '60s, very alive."

But while Nader says he will establish a new national organization

to do lobbying and issue mobilization, this new organization as

yet has no name, no director, no set agenda, and--rather astonishingly--it

will not be a membership group. While Nader says he has "been doing

local fundraisers for the Greens--that's the best way to recruit

new members, and it's easier to get local press," in fact he has

only done two of them (in Providence and Hartford). He says his

new group will be announced several months hence, as will his plans

in relation to the Green Party. "Wait for the spring--the time of

rebirth," he chuckles. He also envisions a series of major rallies--but

the first one won't be until July.

In the hard-nosed real world of electoral politics and communications,

however, timing is everything. Hamlets don't last long in national

politics--just ask Mario Cuomo. And the attention span of the electorate

is a notoriously short one. If Nader does not make up his mind soon

about what he should do, there's a real danger he will have missed

his moment, if he hasn't already.

|