|

When John Sweeney became the president of the AFL-CIO in 1995,

he set organizing a million new members a year as the labor movement's

top priority. Without a turnaround in the four-decade-long decline

in union strength, organized labor faced not only losing its power

in bargaining and politics, but disappearing altogether. Last year,

when the percentage of the work force in unions failed to drop for

the first time since 1975, there was hope that the long slump had

bottomed out.

That celebration was short-lived. In January, the Bureau of Labor

Statistics announced that in 2000 the number of union members had

dropped once again to 16.3 million, representing only 13.5 percent

of the work force, a decline of 0.4 percent from 1999. The character

of the labor movement also continues to change: 37.5 percent of

government workers are organized (a slight increase from last year),

but only 9 percent of the private sector work force now belongs

to a union. While emphasizing that there was still a net growth

of 150,000 members over the past three years, AFL-CIO organizing

director Mark Splain acknowledges that "clearly it's not good news

that the numbers are going in the wrong direction."

Although there are many reasons for the renewed decline, the central

problem is that,

|

|

Despite energized campaigns

like the

janitors' strike in Los Angeles, overall

union numbers keep falling.

DAVID McNEW/NEWSMAKERS

|

despite strong efforts by a few unions, there is still only a spotty

and superficial commitment to organizing at all levels of the labor

movement. "We think there's a crisis," says Andy Stern, president

of the Service Employees Union (SEIU)--one of the most aggressive

organizers in the labor movement--and co-chairman of the AFL-CIO Executive

Council Organizing Committee. "What I'm most concerned about is that

there needs to be more of a sense of crisis from the AFL-CIO and throughout

the labor movement."

The decline of members last year probably reflects heavy job losses

in manufacturing, where union density is relatively high, that were

obscured by overall low unemployment figures. Also unions diverted

much money and staff to politics this year rather than organizing.

There were also some big wins in 1999, such as the 70,000 home health

care workers in Los Angeles, that reflected many years of previous

organizing. The AFL-CIO claims that 400,000 new workers were organized

last year (although the running tally in its "Work In Progress"

newsletter identified only 160,000) compared with 600,000 in 1999

and 500,000 in 1998. But several experts privately express doubts

about the reliability of those numbers.

A few unions are widely acknowledged as organizing leaders, such

as SEIU, UNITE, the Hotel Employees (HERE) and the Communications

Workers (CWA). Other unions that have made major new commitments

to organizing include AFSCME (public workers), the Steelworkers,

the Autoworkers and the Carpenters. But even in these unions, there

isn't universal commitment. For example, CWA locals have resisted

international efforts to increase spending on organizing, and only

a few AFSCME district councils, such as in Illinois, have made organizing

a top priority.

Much of the problem reflects internal union politics: Officials

succeed by catering to members, who often must be persuaded to spend

their dues money on expensive, risky efforts to recruit new members

rather than providing services for themselves. Since nearly three-fourths

of union funds are controlled by often autonomous local unions,

even a committed international union president may have limited

influence. Although last summer the AFL-CIO agreed to hold unions

more accountable to membership goals, the federation has no power

over affiliated unions. Furthermore, despite its continual emphasis

on organizing, the AFL-CIO and its leaders often send the message

that political work is even more important.

When Sweeney came into office, the best estimates were that few

unions spent more than 5 percent of their budgets on organizing.

With a few exceptions--again most notably the SEIU--very few unions

reach the AFL-CIO recommended level of spending 30 percent of their

budgets on organizing. "There are only a very few unions at the

national or local level that have made a dramatic changes," says

Richard Bensinger, the former AFL-CIO organizing director who is

now a consultant to several unions. "Most union commitment to organizing

is still at the level of rhetoric. You can see substantial growth

and commitment in those few, but there's next to nothing in many

others."

The issue is partly money. "There's no way to do this on the cheap,"

Bensinger says. "The law is too weak and employers too vicious to

think we can get by inexpensively." But the more fundamental issue

is changing the internal culture of the labor movement. Starting

with Bensinger's tenure, the AFL-CIO has encouraged union officials

and staff to develop a new outlook on their work. Unions like HERE,

for example, extensively train union stewards to mobilize members

and handle grievances on the job, freeing staff to focus more on

organizing new members with the help of newly energized member volunteers.

This represents a dramatic change from the old "insurance" model

of unions, where business agents handle individual union members'

problems.

Cultural change also demands a new organizing strategy. First,

the best organizing unions have moved away from simply responding

to "hot shop" calls from agitated workers or desperately seeking

new members in seemingly easy targets outside their traditional

realms. Unions like SEIU and HERE build on their strengths to develop

power in particular industries (the two have even swapped locals).

Against great resistance, SEIU's Stern is pushing hard for all unions

to pursue more clearly focused strategies.

Successful unions also approach organizing as a task of building

a union at the

|

|

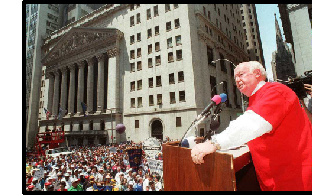

AFL-CIO President John Sweeney

addresses

workers at an "America Needs a Raise"

rally on Wall Street in 1996.

STAN HONDA/AFP

|

workplace even before it is recognized, starting with the creation

of an internal committee of dedicated workers who do most of the organizing.

Union organizers can't succeed with old tactics of handing out leaflets

at plant gates. They must pursue more aggressive tactics such as holding

solidarity days at work, surveying workers about their needs, conducting

actions on the job, or involving the community--including clergy,

elected officials, community groups and the press--in support of workers

who are trying to organize. According to Cornell University researcher

Kate Bronfenbrenner, unions that used five or more of these "union

building" tactics as part of their organizing efforts in 1998 and

1999 were 30 percent more likely to win an NLRB representation election

than unions that did not. In the long run, these tactics are also

likely to build stronger unions, but they have been adopted mainly

because unions needed to counter intense employer opposition.

Consider the case of Certech, a 500-worker unit of the global Carpenter

Technology Corporation that manufactures advanced ceramics for the

auto, aerospace and electric power industries in northern New Jersey.

In 1999 workers from the plant, which primarily employs immigrant

women from Central America, contacted UNITE for their third try

to form a union. The company responded, as usual, with a campaign

of threats, including moving the company to Mexico, bribes and intimidation,

even firing seven union supporters. Last March the workers voted

against unionization.

But the union worked with the core of committed union members to

continue the fight with protests, leafleting and mobilization of

support from clergy, local politicians, other unions and community

groups. That support gave workers courage to testify at hearings

on 70 charges of unfair labor practices that the union brought to

the National Labor Relations Board. As the testimony continued into

the third week, the company called and said it was ready to negotiate

a contract, which was signed at the end of January. The outside

support was essential, but the key was a well-organized group of

workers on the job. "We put our heart into this campaign," says

regional organizing director Rhina Molina, "but nothing can be done

unless the workers decide they want to do it."

At a time when surveys show more than a third of unorganized workers

would like to join a union, the chief obstacle to unionization remains

employer opposition, which exploits labor laws that have grown weaker

over the years. In a scathing report issued last fall, Human Rights

Watch concluded that American labor law fell far short of international

standards. "Many workers who try to form and join trade unions to

bargain with their employers are spied on, harassed, pressured,

threatened, suspended, fired, deported or otherwise victimized in

reprisal for their exercise of the right to freedom of association,"

the group reported.

The problem has only grown worse with globalization. Bronfenbrenner

has found that more than half of employers threatened to close all

or part of the work site during organizing drives, nearly double

the rate of threats in the late '80s. In the most mobile industries,

like manufacturing, 68 percent of employers threatened to move during

organizing drives; those threats cut union wins by about 40 percent.

Although the threats (made as often by financially strong companies

as weak ones) were often idle, 15 percent of plants where unions

won recognition actually did shut down within two years, triple

the rate in the late '80s.

The fierce level of employer opposition still chills union organizing,

despite improved strategies of the best unions. Unions now win more

than half of all NLRB elections (53 percent in fiscal year 1999),

but the number of elections held and workers eligible to vote remains

below even what it was in the late '80s. Partly that reflects a

shift away from NLRB elections to other methods, such as pressuring

companies to recognize the union when a majority of workers have

signed union cards. Yet the overall picture remains grim: Roughly

one-third of the time, unions withdraw even before an election is

held, as employer opposition destroys union support. Even after

winning an election, only 60 percent of private sector workers typically

secure a first contract.

Union organizing increasingly focuses on the nonprofit-private

and public-service sectors, where win rates are much higher (often

60 to 70 percent in sectors like health care and finance) because

opposition is usually less fierce. With the growing influence of

globalization, unions are devoting less effort to organizing in

manufacturing, where they win about 42 percent of elections overall--but

only about 31 percent of elections in the most global companies,

according to Bronfenbrenner. Not surprisingly, multinational companies

are far more likely to threaten to close and move than nationally

based firms.

Unions like CWA and HERE have led the effort to reduce employer

opposition by using their bargaining or political clout to win agreements

from companies to stay neutral during organizing drives. But unions

have also used their political leverage to make sure that publicly

supported local development deals provide for labor peace--no strikes

during organizing in exchange for employer neutrality. California

last year also approved legislation mandating that businesses not

use state funds to oppose unionization. Unions won about two-thirds

of organizing campaigns with neutrality agreements, according to

a study published last year.

It is also possible to curtail employer tactics in less formal

ways. The AFL-CIO has encouraged central labor councils to promote

"the right to choose a voice at work" through public actions. Stern

wants the AFL-CIO to increase pressure on officials who are elected

with labor support to take concrete actions to support union organizing

efforts as well as push for local and state legislation, such as

reversing right-to-work laws and passing legislation prohibiting

public money from being used to fight unions. Splain adds, "The

action for us will be at the local and state level where union density,

strength, ties to the community are pretty good, like Los Angeles."

President Clinton did little to help union organizing, and there

is no prospect for federal legislation to aid organizing in the

near future under Bush and a Republican Congress. Human Rights Watch

recommended a long, reasonable list of reforms that would strengthen

workers rights in the United States, but the greatest value of the

report is in highlighting this country's failure to live up to established

international law and human rights treaties. In a related effort,

the Labor Party has launched a campaign to ground workers rights

in the guarantee of First Amendment rights of free speech and association

at work and in the constitutional prohibition of involuntary servitude,

rather than a focus on reforming existing labor law, which is based

on the federal government's power to regulate interstate commerce.

Ultimately, the most effective campaign for workers rights would

be massive organizing drives--some focused on a particular corporation,

others on a regional industry or other target--that would combine

all of the demonstrated elements of a successful organizing campaign

with a high-profile political and community fight to guarantee workers

rights. It is unlikely that unions will break out of the cage formed

by the law, employer power and globalization until the crisis of

the labor movement becomes a social crisis as well. But first the

labor movement must recognize its own critical condition and be

willing, as the civil rights movement was, to create a social crisis

if workers rights are not respected.

|