|

When the Rev. Jesse Jackson admitted he had an affair with an aide

and fathered a child out of wedlock, media pundits went into overdrive

assessing his new infamy. Conservatives abandoned all attempts to

contain their glee at Jackson's embarrassment, seizing the opportunity

to denounce him for a multitude of sins from hypocrisy to extortion.

Jackson had already infuriated the GOP with his hyperbolic (and

some said hypocritical) protests of the great Florida vote theft.

So the revelations of his sexual indiscretions, especially the news

that Jackson took his pregnant mistress to visit the White House

during President Clinton's own sex scandal, bathed them in a spirit

of pure vindication. Jackson's black supporters, however, fervently

stood by their man and urged his quick return to the fray. Most

of his progressive white supporters also seemed willing to forgive

him (though many would have preferred more than a three-day sabbatical).

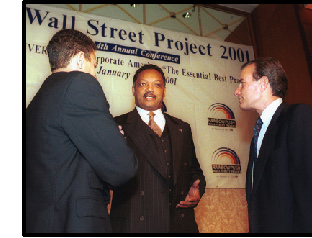

Significantly, Jackson's re-emergence came at the second annual

conference of the

|

|

After his three-day sabbatical,

Jesse Jackson

headed for Wall Street.

SPENCER PLATT/NEWSMAKERS

|

Wall Street Project, an initiative he launched to help bring African-

American business aspirants closer to the sources of investment capital.

The captains of capitalism and their black petitioners (gathered at

Jackson's behest) greeted him warmly in his first post-scandal foray.

But among some African-Americans, this appearance raised more concerns

about the quality of black leadership than any revelations of sexual

indiscretion. Questions about leadership have been rumbling through

the black community with sustained intensity for several years. Don't

African-Americans need new leaders with a more mature global consciousness?

Is the civil rights leadership still relevant?

Many activists are convinced that the anger stirred up by the presidential

election and its aftermath could help power new growth in the civil

rights movement. An "emergency summit" was called by the National

Black Leadership Roundtable on January 4 to capitalize on the new

activist spirit that seems to have sprung from the election protests.

The gathering attracted leaders from the Southern Christian Leadership

Conference, the National Urban League, the NAACP, the Nation of

Islam, the National Bar Association, the Rev. Al Sharpton's National

Action Network, and other black protest and professional organizations.

Several members of the Congressional Black Caucus also attended,

along with a number of black elected officials from around the country.

Although nothing earthshaking emerged from the summit, the gathering

served as a reminder that old-style leadership remains important.

Despite talk of the need for new leadership styles to better deal

with the problems of the new millennium, it's old issues like voting

rights and affirmative action that still stir the masses of black

people. "Jesse Jackson remains a popular figure among African-Americans,

because blacks still believe that the basic fight for civil rights

is still going on," explains David Bositis, senior political analyst

for the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a Washington-based

think tank. In its latest survey, Jackson received a favorable rating

by 83 percent of those blacks polled.

That hasn't quelled vocal, sometime vitriolic criticism of Jackson

from radicals, nationalists and black conservatives. Jackson is

blamed by many progressives for squandering a rare opportunity to

build on the multi-ethnic, left-populist movement that came together

around his two presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988. Jackson

lost his luster when it became clear that he wanted the Rainbow

Coalition to serve as a vehicle of his own design rather than a

grassroots, nuts-and-bolts political organization. Although there

have been concerted efforts to increase the visibility of radical

thinkers, they were excluded from the National Black Leadership

Roundtable. Such an omission is nothing new. Organizers of the Black

Radical Congress founded the group in 1998 to help insert a radical

critique into the discourse, but so far its voice has not been heard.

Most nationalists never trusted Jackson. He was seen as a kind

of "Rev. Leroy," a duplicitous preacher in black folklore, whose

intent was seduction more than salvation. Jackson's current troubles

only bolster that portrayal. He did attract the nationalists' attention

when he aligned himself with Farrakhan in his 1984 campaign; it

seemed to herald an alliance of the divided heirs of Malcolm X and

Martin Luther King Jr. and the beginnings of a black united front.

That alliance soon fell apart, but Jackson has always included issues

dear to nationalists--like economic empowerment and community control--in

his pitch. The nationalists have bigger problems than worrying about

Jackson, however. While the enormous success of the Million Man

March seemed to herald a changing black leadership, Louis Farrakhan

hasn't held onto the imagination of the black masses.

And despite well-funded media megaphones and unwarranted appearances

on political talk shows, black conservatives have yet to stake their

claim on any black constituency. Their "compassionate conservative"

presidential candidate employed more race-friendly symbols than

any GOPer before him, but still failed to capture even 10 percent

of the black vote. Predictions that the growing black middle class

would defect from the Democrats have failed to come true.

For their part, black conservatives tend to hold up Jackson as

an example of all that is wrong with black leadership. He often

is derided as a "poverty pimp" who gains his power only by exploiting

blacks' sense of vulnerability. They argue that Jackson and the

whole civil rights fraternity utilize a myth of widespread black

poverty to more efficiently extract favors from guilty whites. But

given the increasing numbers of black conservatives (as well as

a frothing horde of white critics) who are making this familiar

charge, it's striking that the masses of African-Americans still

support Jackson so solidly.

The 2000 elections have produced a discernible change in the tempo

of the black freedom movement. The revelations about Jackson's sexual

irresponsibility will do little to taint his luster within the African-American

community. In fact, because of the black community's historically

honed impulse to circle its wagons when under attack, the scandal

may in fact add a bit to Jackson's shine.

The issue of whether his leadership is under challenge is more

an issue for whites than for blacks. Whites have always had a vested

interest in limiting the range of black leadership. Throughout African-American

history, the white leadership of the United States has tended to

choose specific figures to represent blacks. In most cases, the

leader was chosen for his (inevitably it was a man) ability to reinforce

the racial hierarchy. With rare exceptions, black people seldom

followed this lead. There's little reason to expect much change

now.

|