|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

It looks a little like one of those press conferences announcing a merger between corporate giants: a couple of middle-aged guys shaking hands and smiling into a bank of cameras. Just like on CNN, they assure the world their new affiliation will make them stronger, better equipped to meet the challenges of the global economy. Only something is askew. More facial hair for one thing: The man on the left has a scruffy beard and the one on the right has a rather distinctive handlebar moustache. And come to think of it, their alliance is not a merger of corporate interests--designed to send stock prices soaring and workers wondering about their "redundancy." In fact, the men say, this merger will be good for workers and lousy for stock prices. Another clue we're not watching CNN: Someone passes a message to the man on the

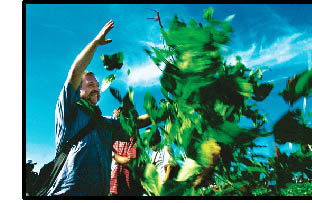

The man on the left is Joao Pedro Stedile, co-founder of Brazil's Landless Peasants Movement. The man on the right is José Bové, the French cheese farmer who came to world attention after he "strategically dismantled" a McDonald's restaurant to protest a U.S. attack on France's ban on hormone-treated beef. And this isn't Wall Street; it's the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil. To read the papers, these men should not be sharing a platform, let alone embracing for the cameras. Third World farmers are supposed to be at war with their European counterparts over unequal subsidies. But here in Porto Alegre, they have joined forces in a battle much broader than any intergovernmental trade skirmish. The small farmers both men represent are attempting to fight the consolidation of agriculture into the hands of a few multinationals, through genetic engineering of crops, patenting of seeds and industrial-scale, export-led agricultural policies. They say that their enemy is not farmers in other countries, but a system of trade that is facilitating this concentration, and taking the power to regulate food production away from national governments. "Today the battle is not in one country but in every country," Bové tells a crowd of several thousand. They break into chants of "Ole, Ole, Bové, Bové, Bové" and, in a matter of hours, hundreds are wearing badges declaring, "Somos Todos José Bové" ("We are all José Bové"). This type of cross-border alliance--a globalization of movements--is the real story of the World Social Forum, which ended January 30 and attracted more than 10,000 delegates. After 13 months of international protests against global trade institutions, the forum was a chance to share ideas about social and economic alternatives. It is a new kind of intellectual free trade: a Tobin tax swapped for a "participatory budget"; national referenda on all trade agreements in exchange for local lending alternatives to the International Monetary Fund; farming co-operative models traded for community policing. But there is one idea with more currency than any other, expressed from podiums and on flyers handed out in hallways, "Less talk, more action." It's as if talk itself has been devalued by overproduction--and little wonder. At the same time in Davos, Switzerland, the richest CEOs in the world sound remarkably like their critics: We need to make globalization work for everyone, they say, to close the income gap, end global warming. Oddly, at the Brazil forum, designed to help talk our way into a new future, it seems as if talking has become part of the problem. How many times can the same story of inequality be told, the same outrage expressed, before that expression becomes a paralyzing, rather than catalyzing, force? Which brings us back to the two men shaking hands. The reason the police are after José Bové (and why he is being treated like a cheese-making Che Guevera) is that he took a break from all the talk. While in Brazil, Bové travelled with local landless activists to a nearby Monsanto test site, where three hectares of genetically modified soybeans were destroyed. Unlike in Europe, where similar direct-action has occurred, the protest did not end there. The Landless Peasants Movement has occupied the land and members are planting their own crops, pledging to turn the farm into a model of sustainable agriculture. Why didn't they just talk about their problems? In Brazil, 1 percent of the population owns 45 percent of the land. In the past six years alone, 85,000 families have joined the ranks of the landless. At the first World Social Forum, the most talked-about alternative

turns out to be an alternative to talking: acting. It may just be

the most powerful alternative of all. Naomi Klein is the author of No Logo. A version of this article originally appeared in the Toronto Globe and Mail.

Now read Saskia Sassen's "How to Confront Globalization: Challenge the Elites"

|