|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

An afternoon stroll through the seemingly sleepy capital of The Republic of Cyprus yields nothing more than postcard-perfect vignettes of life in a typical, mid-size Mediterranean city: winding cobblestone streets, picturesque museums, family-run shops, cats draped over sunny terraces, and a few Gap-like stores frequented by sunburned British tourists. Oh wait--there's also that "Green Line" running down the center of the city, the one that has kept Cyprus divided for the past 27 years. "Turkey's got access to oil," Katarina Demetrious, a Greek Cypriot tour guide, says to me bitterly as we approach the Green Line. "We have no oil--if we did, the United States would never have allowed this to happen." Demetrious refers not so much to Turkey's initial military invasion of Cyprus in 1974, but to the occupation the Republic of Cyprus has had to endure. With the exception of a few heated months during the summer of 1974--when Henry Kissinger's name was angrily shouted at protests throughout southern Cyprus and in Washington--the U.S. government and most E.U. member states have done an excellent job of whitewashing Turkey's possession of northern Cyprus. Now, with tensions mounting between Ankara and Brussels--over Turkey's increasingly aggressive bids for E.U. membership--Greek Cypriots are moving back into the international spotlight. Nicosia's Green Line actually was created at the end of 1963, three years after Cyprus

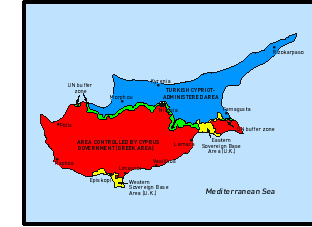

Per capita, Cyprus is the most militarized country in the world after North and South Korea; there are 35,000 Turkish and Turkish Cypriot troops, 14,500 Greek and Greek Cypriot troops, and 1,200 U.N. soldiers on the island. Standing on the Greek Cypriot side of the U.N. observation post at the east end of Nicosia, Demetrious and I stare into the buffer zone, about 160 feet of uninhabited space designed to keep the two sides apart. None of the island's 190,000 Turkish Cypriots and Turkish mainland settlers or 655,000 Greek Cypriots can enter the buffer zone without special permission. Squinting as hard as I can, I see nothing but rotting buildings, litter and debris, and just a little farther on, a prominently displayed Turkish flag. "Where are all the Turkish soldiers?" I ask as we climb down. Greek Cypriot soldiers mill freely around, machine-guns hugging their waists. "The Turkish government won't place soldiers here because of the observation post," my guide informs me. "They're afraid there could be incidents that would involve tourists." Under normal circumstances, keeping a lid on the simmering anger around the Green Line isn't a big priority for Turkey--its strategic location during the Cold War practically guaranteed carte blanche as far as the Western powers were concerned. But these days, desperate to join the European Union, which it hopes will bring much-needed foreign investment and employment in the country, Turkey is struggling to downplay its militaristic past. Yet even now, more than a decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall, officials from the United States and the European Union are reluctant to move beyond diplomatic wrist-slapping with Ankara over its continued occupation of Cyprus. Both entities feed weapons and funding to the country on a regular basis, although the United States is by far its biggest supplier. A 1999 report by the World Policy Institute documented more than $5 billion in U.S. arms transfers to Turkey during the Clinton administration alone. In December 2000, the IMF agreed to pump another $10 billion in credit and loans into Ankara's empty pockets. Once again, Turkey's geopolitical importance is its trump card. In addition to its long-regarded strategic importance, oil and other natural resources have been discovered in the nearby Caspian Basin, and the United States is loathe to do anything that would anger Turkey and disrupt plans for the Baku oil pipeline. However, as these two governments continue with business as usual, the European Union is growing increasingly nervous about the idea of accepting Turkey as one of its own. When Turkey first invaded Cyprus in July 1974, it claimed it was protecting the island's Turkish Cypriot community--a remnant of Cyprus' time as an offshoot of the Ottoman Empire. Although the main culture and language of Cyprus has always been Greek, the island has passed through a dizzying array of hands--Byzantine, Frankish, Venetian, Ottoman and, finally in 1878, British. Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot communities lived together in relative peace under British rule until the 1950s, when a guerrilla movement for independence began to form on the island. The National Organization of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA) wanted the British out of Cyprus. The British wanted to retain Cyprus as their Middle East base and involved Turkey in the issue to counter the Greeks at the United Nations. What concerned Turkey--and the Turkish Cypriots--was that the EOKA supported enosis, or unification with mainland Greece. The south coast of Turkey lies only 47 miles away from Cyprus, and the Turkish government would not tolerate a Greek military presence so close to its borders. After a few years of communal violence, the British raised the specter of partition between Greece and Turkey, an unacceptable solution since Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots were scattered throughout most of the island. Archbishop Makarios III, the Greek Cypriot leader, agreed to the idea of independence instead of enosis. The British arranged a meeting at Zurich with Greece and Turkey to draft an independence accord, with a set number of Greek and Turkish troops to be stationed on the island, sovereign bases for Britain, and constitutional provisions that could not be altered. The result was a nightmarishly awkward constitution that provided for a Greek Cypriot president, a Turkish Cypriot vice president and a parliament that allotted the Turkish Cypriots, 18 percent of the population, veto power and 30 percent of the parliament and civil service. In 1960 the Republic of Cyprus was born, with Makarios as president. The constitution soon proved unworkable and the violence resumed. By late 1963, the Green Line was established in Nicosia, but that didn't help. Fighting escalated to the point where the United States, which wanted NATO control of the island to keep the Soviets out and ensure continued operation of U.S. listening facilities that had been established under the British, attempted to introduce a NATO force. Makarios insisted on U.N. peacekeepers instead. Turkish Cypriots fled, or were forced to flee, into enclaves, raising the possibility of partition. Eventually the violence was brought under control, and intercommunal talks for a new constitution began in 1968. The talks came close to reaching a final agreement in early 1974, but with Cyprus seeming to slip out of the mainland's grasp, both Turkey and the Greek junta in Athens made plans to ensure that didn't happen. In mid-July, a small unit of right-wing Greek officers staged a coup against Makarios and seized control of the government; Turkey's invasion seemed a foregone conclusion. The United States, which had been given advance notice of the Greek junta's plans, pretended that it was an internal affair and blocked a U.N. Security Council demand for cease-fire. Somewhat later, the Nixon administration dispatched a high-level diplomat, Joseph Sisco, to the region in a belated effort to get Greece and Turkey to agree to a replacement for Makarios. It was too late: 6,000 advance Turkish troops were on their way, landing in Kyrenia, a small village on the north coast of Cyprus. Greek Cypriots who fought against the island junta blamed Nixon for the invasion. Indeed, Nixon's Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, wanted Makarios ousted to bring the island under the control of someone more likely to do NATO's bidding. Kissinger's name was cursed repeatedly in street demonstrations all over the southern half of the island. To most political observers, Turkey's invasion came as no surprise. Some Greek Cypriots even welcomed it initially, assuming Turkey's presence would rid the island of the fascist junta that drove Makarios into hiding. But when Turkey followed up its initial July invasion with a second one in August, pushing south until it captured the wealthy city of Famagusta, Greek Cypriots realized Ankara was playing for keeps. All in all, Turkey carved out 37 percent of the island's territory for itself, most of it located on the northern coast. The Turkish military began a village-by-village expulsion of Greek Cypriots from the occupied area. Greek Cypriots, fearing the realization of Turkey's long-held goal of partition, tried to prevent Turkish Cypriots from fleeing north. In August 1975, an agreement was reached to allow 40,000 Turkish Cypriots to move north under U.N. escort, in exchange for an end to expulsions and the return of some of the 175,000 displaced Greek Cypriots--an agreement only partially honored by the Turkish side. This deal played right into Turkish hands. "Once northern Cyprus was given over to the Turkish Cypriots, Turkey brought in thousands of ethnically Turkish peasants from the Anatolian heartlands," says Heinz Kramer, author of The Changing Turkey. "In effect, they repopulated parts of the island to make it more Turkish." Despite cries of protest from Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots--who also resented the peasants' presence--nobody from the international community came to their aid. In 1983, when the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) finally declared itself to be an independent state--unrecognized by nearly every country except Turkey--all but the most diehard Greek Cypriot refugees realized they would not be going home. The European Union is set to inherit the latest phase of this 27-year-old problem. In November, E.U. member Greece persuaded its 14 partners to add resolving the division of Cyprus and long-standing territorial disputes in the Aegean Sea to the list of short-term actions that Turkey must carry out before the start of membership negotiations. Turkish Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit accused the European Union of duping his

The fly in the ointment in all of this is Cyprus itself. Buoyed by Greece, Cyprus has been placed on the fast track for E.U. membership by 2004. Although most member states would rather not accept Cyprus until "the issue" is resolved, Greece threatened to veto membership applications for Poland and Hungary if Cyprus was not accepted as well. Dedicated to eastern enlargement, the European Union had no choice but to issue ratification papers to Cyprus, which delineate the economic goals the island must achieve prior to acceptance. With its relatively well-developed infrastructure, heavy tourism industry, and single-minded determination to join the European Union, Cyprus has a major leg up on Turkey, which is saddled not only with economic woes but massive human rights violations. If accepted as an E.U. member, Cyprus would certainly be well within its rights to use its member veto power to force Turkey into a head-to-head dialogue about the occupied territory--something it has been trying unsuccessfully to do for 27 years. "What would Turkey do?" Kramer asks. "It can't invade Cyprus if it is an E.U. member state, and if it did, the European Union would likely deploy troops there." In an ironic twist of fate, the Turkish Cypriot community is among the most excited about Cyprus' prospective E.U. membership. Isolated by international policies that refuse to recognize the TRNC as a legitimate state, and vastly outnumbered by their Anatolian counterparts--with whom they have little in common--many Turkish Cypriots spent the summer demonstrating against TRNC leader Rauf Denktas, whom they accuse of blocking negotiation talks with Greek Cypriots. The Republic of Cyprus has offered Denktas and Ankara several versions of its plan for a unified island, basically one federal government with proportional representation overseeing two relatively independent states. Denktas and Ankara have responded with their version, which insists that the legitimacy of the TRNC government be recognized. Last December, Denktas refused to attend the sixth round of Cyprus talks in Geneva unless the European Union and United States recognized the TRNC. Neither did, leaving Denktas out in the cold. Turkey further alienated itself from the West in December, when it refused to give the European Union access to its NATO resources to build a European-based, 60,000-member rapid-reaction force. (Washington was particularly anxious that NATO bases be used so it could share information and keep tabs on E.U. forces.) Turkey feared that these troops could be deployed against it if the situation in Cyprus gets out of hand. One thing remains clear: The status quo in Cyprus cannot be maintained

forever. If the European Union can't bring about a deal before 2005,

all the existing rules are going to be broken--and for the first

time in its millennia-long life, Cyprus could be the one sitting

in the catbird seat. V.A. Otis, a correspondent for New York's WBAI radio, also writes for The Village Voice and Ms. magazine.

|