|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||||

|

It would be easy, from afar, to believe that Nigeria, Africa's most populous nation, is moving admirably away from its violent and troubled past and is, in fact, quite ready to take up the role of West African superpower that G-7 nations desperately want it to be. The democratically elected administration has withstood two years without a coup. Nigeria's notorious military is learning--with the help of U.S. Special Forces--the often ambiguous skills of modern peacekeeping in preparation for yet another intervention in Sierra Leone. And perhaps most important, in an acknowledgment of the country's troubled past that's rare for an African country, the new administration has impaneled a Human Rights Violations Investigation Commission in an effort to atone for the sins of a long succession of tin-pot dictators. But that's the superficial view of present-day Nigeria. Sadly, the new Nigeria greatly

And the Human Rights Violations Investigation Commission, roughly modeled on South Africa's cathartic Truth and Reconciliation Commission, is, in the eyes of many Nigerians, hardly providing an opportunity for healing and release. Instead, its investigation into allegations of past atrocities committed by various and sundry military and police officials is widely regarded as an insulting waste of time that is serving more to marginalize the complaints than to reconcile them. This could be the most damaging failure of modern Nigeria. Instead of a cleansing of the national soul, many of the country's citizens believe the commission's goal is a whitewashing of Nigeria's past for the sake of its emergence as the latest West African democratic success story. According to most opinions, Chief Justice Chukwudifu Oputa, chairman of the Human Rights Violations Investigation Commission--commonly called the Oputa Panel--is a qualified jurist with impeccable credentials. But even those aren't good enough to overcome the commission's inherent flaws. "If you want to draw a comparison, the difference I saw with the South African example is that the participants actually came out and confessed," says Williams Wodi of the University of Port Harcourt. "In the Nigerian example, what we saw was like a circus. Nobody ever came out and said 'I did this.' That is the contrast and the failure for me. No one pleaded for reconciliation for their sins." No one necessarily had to, he adds. The commission is charged with the overwhelming responsibility of investigating allegations of mysterious disappearances, extrajudicial executions, torture, assassinations and other abuses from January 1966 through June 1998 with little or no funds: Seven months after his inauguration, Obasanjo's administration still hadn't passed a budget, initially paralyzing the commission. More than 10,000 cases from Ogoniland alone--a small region of high-profile tension and violence in the oil-rich Niger Delta--were submitted to the commission. The sheer volume of cases required consolidation of some and seemingly arbitrary rejection of others, which resulted in an early blow to the commission's credibility. In addition, the commission has no authority to compel witnesses or defendants to testify and cannot offer immunity or amnesty in exchange for truthful testimony. Thus many Nigerians assume that military leaders who voluntarily take the stand are lying to avoid implicating themselves. "It is a waste of time and a waste of resources," says George Nafor, a resident of the small Ogoni village of Ebubu. "Maybe if reconciliation happens, it would be worth it, or if people confess and become better from confessing. But nobody confesses. They all deny." Wodi himself testified before the Oputa panel as a witness to the machete death of Senate minority leader Obi Wali, who was outspoken in his criticism of the government. Wodi named names and provided enough evidence that Oputa ordered the head of the police in Abuja to reopen the investigation into the murder. But the accused ignored orders to appear before the panel and by March, three months after Oputa ordered the new investigation, nothing had been done. "It was an experience of anger," Wodi says. "I named people who killed this man. His murder was very unjustified and needed to be talked about, so on that level, yes, I suppose it was beneficial to have it out in the air. But on an institutional level where it matters most, it did not achieve anything because the panel is not empowered to summon people and put them through all the rigors of a society governed by laws." One of the revealing facets of the hearings, however, was that they provided a glimpse into how the government has been self-succeeding, even under the guise of "democracy." Former Army Chief of Staff Major Gen. Ishaya Bamaiyi testified that, shortly after the 1998 death of Gen. Sani Abacha, the most recent of Nigeria's most ruthless leaders, he was called into the office of Abacha's successor, Gen. Abdulsalam Abubakar, to discuss who should be the country's next leader. "When Gen. Abubakar invited me to his office," he says, "he told me of his government's resolve to consider an ex-military officer to be the civilian president." The man chosen to run with the general's backing was Obasanjo, who ruled Nigeria

It's significant to note that many of the more important figures from Nigeria's darker days have been given a wide berth by the Oputa Panel, most notably Ibrahim Babangida, a former military ruler and mastermind behind several of the country's bloodiest coups, including the one that brought Abacha to power. "Big flies somehow pass through this net," Wodi observes, "99.9 percent of those in government are all products of Abacha and Babangida. Those people are backing the government to shed their skins. They impressed the West so much, but there's not one of them who can stand up and claim to be a democrat." In spite of the commission's shortcomings, many see a silver lining to the public hearings. "It is good that these things are brought out," says Ebubu Chief Isaac Osaro Agbara. "Whether the government is going to do anything to alleviate the trauma that has passed through we still must see. However, even the most tragic government is better than the military." Through the public airing of grievances, Wodi says, Nigerians have become more aware of their suffering at the hands of those in power and they aren't likely to allow it to happen again. "Nigeria today is not the Nigeria of yesterday," he says. "People are becoming more enlightened. The military police are not a match for an angry people." Nowhere is such anger more evident than in Ogoniland, a humid 400-square-mile tropical region in the heart of the Niger Delta's oil fields. For decades, the Delta has vividly illustrated the corruption of the military juntas that have defined the country's character for most of the past 30 years. While six international oil companies extract a combined 2 million barrels of crude oil per day from the Delta--and provide royalties to the government that amount to 80 percent of federal revenue--the approximately 7 million people in the oil regions live in such poverty that the term "abject" seems quaint. Electricity, potable water, medical facilities and competent educational programs are rare amenities in most Delta villages. Pleas for equitable wealth distribution have been routinely ignored, leading to violence in the form of kidnapped oil workers, sabotaged pipelines and interethnic warfare as communities fight over coveted oil jobs with all the passion of hungry dogs over table scraps. Whenever the unrest threatens oil production, the military has been summoned, often with scorched-earth consequences. Delta residents not only have remained poor, but under the ever- tightening screws of authoritarian rulers whose personal wealth often has been derived from the oil royalties. Abacha alone is suspected of having siphoned off as much as $2.2 billion from the Nigerian Treasury. In theory, the military rulers are gone, although several police roadblocks still host

Bane is the hometown of the Delta's most famous figure, Chief Wiwa's son Ken Saro-Wiwa, the playwright who orchestrated the most successful campaign--albeit one riven with internal strife--to publicize the inequities in the Delta in recent history. He was the golden-child spokesman for the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), a politically astute resistance organization that won favor from activist groups worldwide. Such support didn't translate into protection, however. When a U.S. contractor for the Shell Petroleum Development Corporation--the Nigerian arm of Royal/Dutch Shell--was confronted by protesters in Ogoniland in April 1993, the military was called in. Security forces opened fire when the protesters refused to disperse, and, after three days of clashes, 11 people were wounded and one was killed. This set off retaliation attacks by MOSOP's youth wing, the National Youth Council of the Ogoni People. Clashes in Ogoniland escalated in the weeks leading up to that year's presidential election--which was subsequently nullified by Babangida--and culminated in massacres of civilians in the village of Kaa and along the Andoni River. At the height of the problems, Shell collaborated with the military

to restore regional oil operations, which had been suspended due

to the violence. To resume production, Shell later admitted that

it provided supplemental wages to the security forces in the area.

According to a secret memo uncovered by Delta activists, the operation's

goals were chillingly detailed: "Wasting operations during MOSOP

and other gatherings making constant military presence justifiable";

"wasting targets cutting across communities and leadership cadres,

especially vocal individuals in various groups"; and "wasting operations

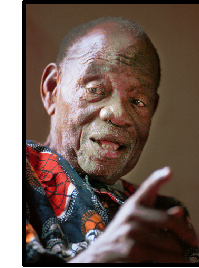

coupled with psychological tactics of displacement/wasting Ten days after the memo was written, on May 13, 1994, the "wasting operation" against Saro-Wiwa went into effect. He was arrested along with MOSOP leader Ledum Mitee for supposedly inciting a riot that ended in the deaths of four conservative Ogoni leaders. According to Human Rights Watch, in the wake of the killings, security forces rampaged throughout Ogoniland, executing civilians, raping women and destroying homes. Saro-Wiwa was found guilty of the charges by a special tribunal, even though no credible witnesses were ever presented to back the government claim that he incited the crowd that committed the murders. No one even placed him at the scene of the crime. Two of the prosecution's witnesses later admitted they had accepted bribes to provide false testimony. Though the tribunal was globally condemned as fraudulent, Saro-Wiwa and eight others were hanged on November 10, 1995. It comes as little surprise, then, that when Oputa traveled to Bane to speak with Chief Wiwa about his son's case, the judge was greeted with deep skepticism that the commission could do anything of value to atone for a past as ruthless as that in Ogoniland. "They came here in this place," Chief Wiwa says. "But if they were wise enough, why don't they see the truth?" In a modest cinder-block room furnished with stiff chairs and outdated calendars, Chief Wiwa dismisses the notion that justice or reconciliation can be found through the Nigerian government. The commission, he says, "is like getting medicine after death. God will punish Nigeria because of the punishment they've given to my son Ken. Can they pay for all these people they've killed in Ogoniland or all the houses they burned or all the crops they looted? God will decide." For the Ogonis and other ethnic groups that live in the Delta, atonement has much less to do with talk than it does with action. Living in an impoverished region polluted by endemic oil spills, ablaze with the light of gas flares that burn around the clock and denied the financial benefit of the oil wealth that lies literally beneath their feet, atonement can only find a foothold if their decades-old pleas for justice and fair treatment are heard in the presidential palace and acted upon. There's little indication that such a thing is likely to happen anytime soon. First of a two-part series. Next issue: Despite a new democratic

government, the Niger Delta is still a polluted wasteland, where

frustration with oil companies and lax federal oversight of their

operations is rising to dangerous levels. Greg Campbell is a freelance reporter living in Colorado. He's currently working on a book about diamonds and their impact on the civil war in Sierra Leone.

|