|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||||||

|

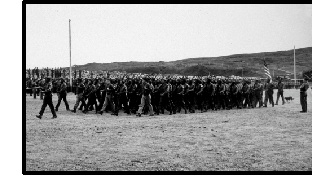

Eyewitnesses say they saw a mass killing--a thousand African-American soldiers gunned down by the Army in a racially motivated shoot-out in Mississippi in 1943. "We had the whole area sealed off--it was like shooting fish in a barrel," alleged one white military policeman more than 40 years later. "We opened fire on everything that moved, shot into barracks. ... We shot every nigger that moved. The screaming, yelling and begging was horrible." The story, whispered around Centreville, Mississippi since World War II, goes like this: Members of the 364th (Negro) Infantry Regiment were killed at Camp Van Dorn to silence their relentless--and sometimes violent--demands for equality in a segregated Army. Some swear they witnessed the shoot-out or events that led to a shoot-out or its aftermath. Some say the casualties were many, others say just a few. Some testimony claims to be first-hand, much is just hearsay. Within days of the arrival in southwest Mississippi of this black regiment with a

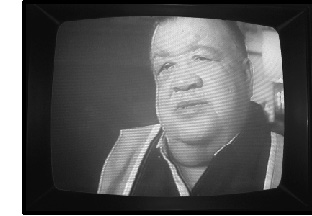

There is no agreement about what happened next. The Army contends the incident passed with no further loss of life. But gaps and inconsistencies in the official records dispute such finality. Those gaps are being filled in by witnesses who claim that racial violence continued throughout the summer, culminating in a cataclysm in which more members of the 364th--the claims range from dozens to more than 1,000--were killed. The most extreme charges add that the bodies were buried in a mass grave somewhere on the sprawling base, or "stacked like cordwood" and shipped north in boxcars. Unbelievable? Yes, says the Pentagon. A 1999 Defense Department investigation of the allegations found, in the words of a spokesman, that "nothing egregious happened." However, critics--including this writer--insist the error-filled report does not pass scrutiny and are still digging for answers. What really happened to the soldiers of the 364th? The fragmentary records of 1943 must be read in the context of the unprecedented racial violence that was sweeping the nation and threatening the war effort. The claim of 1,000 dead sounds incredible. But the volatile mix of armed black militants dropped into a hostile racist environment make it seem more believable. And the looming Nazi threat could have made a cover-up--even among people of goodwill, even among the news media, even among blacks themselves--an act of patriotism, however agonizing. For this story finally to be put to rest, contradictions in the Army's report must be reconciled; thousands of pages of intelligence reports from the era must be accounted for; and more than the handful of soldiers tracked thus far must be found. What's at stake here goes beyond whether one incident reached unthinkable proportions. A generation of white men--the so-called "greatest generation"--would benefit from unprecedented postwar prosperity. Black soldiers, on the other hand, were systematically denied access to the benefits of serving their country. Hundreds of murders and beatings were the most brutal manifestations of this, but unwarranted dishonorable discharges, court martials and widespread discrimination deepened the racial divide. These men, and their descendants, deserve to know the full story. In 1985, a former McComb, Mississippi banker named Carroll Case first heard the tale of wholesale killing of blacks at Camp Van Dorn from William Martzall, a former MP from the 63rd Division, who claimed to be one of the shooters. Case pursued the story on his own for five years. He talked to area residents who worked at the base and claimed to have witnessed the shoot-out or seen evidence of its aftermath, like bloody laundry. University of Southern Mississippi History Professor Neil McMillen gave Case documents from the National Archives concerning the incident, including desperate letters from members of the 364th after the Walker killing and an intriguing Army Inspector General's report that referred to "drastic and untried" actions the Army should take to flush "troublemakers" from the unit. In 1990, Case passed copies of his files to Ron Ridenhour--an award-winning investigative reporter perhaps best known as the soldier whose letters to Congress prompted investigation into the My Lai Massacre during the Vietnam War. Ridenhour interviewed dozens of white and black soldiers and base civilians about the alleged incident. Through the Freedom of Information Act, he obtained tens of thousands of government documents. Ridenhour was nine years into his research on alleged killings at Camp Van Dorn when he died of a heart attack in May 1998. At the time of his death, he had compiled an intriguing but purely circumstantial case pointing to the deaths and disappearances of at least some members of the 364th. Following Ridenhour's death, Case penned his own book on the subject, a mix of fact and fiction called The Slaughter: An American Atrocity. Case alleges that white soldiers gunned down more than 1,200 black soldiers in and around their barracks in the fall of 1943 and then buried their bodies in a mass grave on the base. Case's book includes interviews with Martzall as well as two white civilians, Luther Williams and his brother-in-law W.M. Ewell, both of whom claim to have seen evidence of a massacre, including hundreds of bodies. The shocking allegations in Case's controversial and oft-maligned book caught the attention of NAACP leaders, who, along with Democratic Mississippi Rep. Bennie Thompson, pressured the Army to investigate. Its report, released on December 23, 1999, concluded: "All available material clearly supports the conclusion no incident such as that described in The Slaughter could have taken place." William Leftwich III, deputy defense secretary for equal opportunity, spoke to the press more forcefully: "With what we have done, the DOD and the Army ... have put a stake in the heart of this vicious, maniacal ... rumor." But the report, prepared by the Army Center of Military History, is riddled with factual errors and historical gaps, suffers from internal contradictions, and conflicts with other Army records. The controversy is far from settled. The latest development is the airing of Greg DeHart's documentary The Mystery of the 364th, scheduled to premiere on The History Channel on May 20. "Originally we came into this thinking it was a story about the persistence of urban myths," says DeHart, whose other films include less controversial reminiscences of World War II. "But the cumulative effect of the circumstantial evidence and oral histories from people in Centreville, together with the Army's personal attacks against me, have to make you wonder. There are still a lot of questions that the Army has not responded to." DeHart has called for an independent investigation to re-open an inquiry into the fate of the 364th. It is a call that I second. As Ridenhour's editor at several alternative newsweeklies around the country, most notably the Phoenix New Times, I was well familiar with his painstaking research methods in stories exposing secret CIA training bases in the '70s and the infamous Garden Plot/Cable Splicer plans for suspending civil liberties and instituting martial law in California during those tumultuous times. With the permission of the Ridenhour family, and the assistance of New Orleans attorney Mary Howell, I have thoroughly reviewed Ridenhour's materials, including his unfinished book manuscript and have continued to pursue the story where he left off. The military in World War II was not "Colin Powell's Army," as some call today's

The War Department justified its racist conduct with Army War College studies like the so-called "Bly Report," issued in 1925 in response to racial problems during World War I. Among the reports' pseudo-scientific claptrap on the smaller "cranial cavities" of blacks is this sweeping assertion: "The Negro does not perform his share of civil duties in time of peace. ... He has no leaders in industrial or commercial life. He takes no part in government. Compared to the white man he is admittedly of inferior mentality. He is inherently weak in character." With this as a blueprint, it is no surprise the military establishment resisted black participation despite the threat of World War II. There were riots in some cities when blacks were turned away from induction centers. Though historians argue over Franklin Roosevelt's political motives, the president appears to have been as adamant about a 10 percent quota for blacks in the Army as he was about his threat to withhold defense contracts from companies discriminating against blacks. White workers in shipyards from Mobile, Alabama to Chester, Pennsylvania rioted against the president's directives. In 1943 in Detroit, at about the same time the first race riots were reported at Camp Van Dorn, white workers enraged by black participation in the burgeoning war industry rioted for three days. The final toll: 25 blacks and nine whites killed, hundreds injured, millions of dollars in damage. Much of what we are learning about this racial violence is coming from declassified documents from an extensive wartime domestic intelligence operation. And much of what we don't know about the period is the result of government press censorship--the proportions of which are not understood even today. What's clear is that things were bad all over. There were hundreds of bloody domestic firefights involving black soldiers--sometimes under attack by MPs, sometimes by white civilians--from Fort Dix, New Jersey to Camp Benning, Georgia to Beaumont, Texas. A November 1942 memo to Secretary of War Henry Stimson from his aide Truman Gibson detailed "violent and abusive treatment of Negro military personnel by civilian public authorities in the South." It listed incidents in Alexandria, Louisiana; Columbia, South Carolina; Norfolk, Virginia; Mobile and Montgomery, Alabama; Beaumont, Texas; and Little Rock, Arkansas. Gibson concluded: "This continuing wave of violence may lead to rioting at any time and certainly it is raising havoc with the spirit of Negro soldiers, many of whom have reached the stage that they would rather fight their domestic enemies than the foreign foe." Indeed, some African-American servicemen were active in a grassroots civil rights movement called "Victory at Home, Victory Abroad." The "Double V" movement had no leaders, but some of its adherents were passionate. According to Army intelligence files, at least 26 "troublemakers" in the 364th Regiment were "members of the Double V," and some had the insignia burned or carved on their chests. The 364th Regiment had its origins in the 367th (Negro) Infantry Regiment, which was activated as a black combat unit in March 1941 at Camp Claiborne, in central Louisiana just outside Alexandria. In December of that year, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. But beneath the veneer of a country united in its hatred of the enemy, racial turmoil simmered. Just a month after Pearl Harbor, violence flared in Alexandria. In a pattern that would repeat itself hundreds of times in the years to follow, a black soldier in town with a pass was accused of accosting a white woman. He was set upon by police. His buddies fought back. Military police responded. People were wounded and killed, and property was destroyed. Even the Army report at the time characterized the situation in Alexandria as a police riot. But one local newspaper reporter then, and investigators now, say that the Army understated the severity of the so-called "Lee Street Riot" and undercounted losses. This minimization, some charge, is another oft-repeated pattern. At any rate, the 367th was broken up in March 1942. The official records of what happened are sketchy, contradictory and confusing. But most researchers agree that the regiment's First Battalion--about 1,000 enlisted men--received orders for overseas deployment. The remaining two battalions were redesignated as the 364th (Negro) Infantry Regiment. The 364th took in a batch of new recruits, mostly from Northern cities like Chicago, New York and Philadelphia, and was ordered to Arizona in June 1942. By fall, the full regiment was bivouacked at Papago Park in Phoenix. Letters from soldiers there and official Army investigations deplored the plight of the 364th soldiers, both on base and in the hostile surrounding community. An anonymous letter addressed to Sen. Joseph Guffey (D-Pennsylvania) described the situation: "If there is no change here, all of us from Pennsylvania have decided to go AWOL rather than be murdered in uniforms of the United States Army. Your delay, sir, can be the cause of a disgraceful consequence." On November 13, fighting broke out between black soldiers in the outdoor stockade

Studies at the war's onset had warned that domestic racial problems posed a threat to troop mobilization and arms production that could lead to sabotage. Agents for the Japanese were already promising Southern blacks--their "brothers in color"--freedom from white oppression. Each report of racial violence that leaked out made its way via German and Japanese broadcasts to American soldiers overseas. A mid-war intelligence-led opinion survey suggested that 10 percent of the black population thought they would be better off under Japanese rule. Another study, "The Negro Problem in the Army," circulated by Maj. Gen. George Strong in June 1942, was adamant that "as little movement as possible be made of Negro troops into areas where racial relations are different from their home environment." Such advice was not heeded when the rebellious 364th was sent to the nation's epicenter of racial hate and violence. The 1999 Army report acknowledges a state of strained race relations as the 364th began arriving by train in Centreville on May 26, 1943: "To a majority it was a trip into a virtually unknown and foreign land where a man of color often had to fear for his life." These fears, according to declassified files uncovered by Ridenhour, were not unfounded. "Before the 364th came in, there were several unsolved murders of Negro soldiers," reported Cpl. Wilbur T. Jackson of the 512th Quartermaster Regiment, another segregated black unit. "Their bodies were found in the field. All the white farmers and civilians are armed at all times and seem to want a pitched battle with Negro soldiers." In a memo forwarded to the War Department, Jackson continued: "[Negro] Men have been constantly molested and beaten by white MPs." Jackson said he was willing to testify anywhere, anytime about what he had seen, concluding his memo: "I'd rather die for something I really did than to be shot down because some officer doesn't like the way I walk, or the look on my face." Violent racial clashes began at Camp Van Dorn and in nearby towns within 24 hours of the arrival of the 364th. Though there is much dispute over the details, the record reflects some consensus truths: • Soldiers of the 364th claimed they were going to "clean up" the base and surrounding towns, challenging Jim Crow laws at every turn. • White civilians were heavily armed, braced for a violent clash. • The Army high command in Washington warned base and regimental commanders that they were to end racial violence or lose their jobs. • On May 30, while scuffling with white MPs near the entrance to the base, Pvt. William Walker was killed by the local sheriff. • Members of Walker's company, joined by others, broke into base storerooms, stole rifles and headed for Centreville, vowing revenge. The largest newspaper in the region, the McComb Daily Enterprise, reported on June 3, 1943: "Many wild rumors floated about ... rumors of men being killed by the scores and of women being molested. All efforts to run these rumors down did nothing more than to emphasize the chaotic way the public has of reacting to emotional disturbances." There was chaos to be sure. The 364th's "Morning Reports," a kind of company-by-company daily attendance sheet, note dozens of soldiers as AWOL following the Walker shooting and its aftermath. Files in the National Archives trace some who made their way north, seeking asylum at their local induction boards from what they called a life-threatening situation. A white officer in Walker's company interviewed by DeHart estimates 60 of his men--about half--were among those AWOL. Some white soldiers on the sprawling base heard stories about the violence that they related in letters home. These letters were among the domestic counterintelligence files unearthed by Ridenhour. In a letter dated June 6, 1943, and intercepted by military intelligence, Pvt. Harold F. Jones of the 394th Regiment wrote to a friend about racial violence that broke out with the arrival of the 364th: "They started tearing down their barracks and PXs. Finally they worked over some MPs and killed two white officers. That night they captured five officers and held them in their barracks as hostages. Two battalions of the 5th Infantry were sent in. ... Our officers told us they carted 30 dead niggers to the morgue ... but I don't know if that's true." Another member of the 394th wrote on June 5: "A nigger regiment kinda took things in there [sic] hands and overran a few places. Result. They settled there [sic] hash with gunfire. A few of the niggers were killed. They killed a few white officers though. ... The Fifth Inf. was sent in to take over the riot and the niggers held them off by holding a bunch of officers as hostages." A soldier in the 163rd wrote home in June: "There have been 20 or 25 Negros [sic] hurt and kild [sic]. They [sic] have been 5 or ten shot right through the head ... and we are going to give them hell when they come around us." A June 1 letter written by a member of the 364th stated: "We are catching hell here. Two of our men have been kill [sic] and we have only been in this camp for six days. Something worse is going to happen soon." The patchwork of official records following the first days of violence at Camp Van Dorn does little to sort fact from fiction. Among the problems: • Military personnel records crucial to the incident, along with millions of others, were destroyed in a fire at a federal repository in St. Louis in 1973. • Intelligence files Ridenhour sought from the National Archives did not arrive for six years. When he finally received them, they were incomplete. • The 364th's Regimental Journal shows no entries from May 20, 1943, just before the 364th arrived in Mississippi, until November 4, 1943––almost the entire period in question. • The journal pages, starting in 1942, are signed by a Sgt. Malcolm LaPlace, who told Ridenhour--and whose service record confirms--that he wasn't in the Army in 1942. • After the Army's initial research in 1999 proved "inconclusive," it received a waiver of privacy concerns and based some of its conclusions on records that are not available to the public through the Freedom of Information Act. In short, the official records are a mess, neither proving nor disproving much of anything. Media accounts are not of much help either. At the time, the black press--and white media--readily submitted to increased censorship. There are records of editors calling the War Department for clearance to run stories deemed "inflammatory." There are drafts of newspaper stories stamped "No Objection To Publication." Access to bases and information was restricted. According to current Army spokesmen, the black press had full access to the camps, black soldiers and accounts of racial violence. But on July 19, 1943--just two days after a round of secret court martials tied to the Walker shooting and its aftermath ended at Camp Van Dorn--Secretary of War Henry Stimson wrote to Attorney General Francis Biddle, saying he would no longer stand for black press reports on racial violence in the military. "It is strongly urged that your department take appropriate action to eliminate this serious threat to the war effort," he wrote. What that action entailed has yet to be unearthed from the National Archives. But a study of the one of the nation's most influential black newspapers of the time, the Pittsburgh Courier, shows that all mention of its own militant "Double V" campaign ends within 60 days after Stimson's letter to Biddle. When a reporter for the Courier inquired about the court martials at Camp Van Dorn, base commander Col. Robert E. Guthrie responded in a letter dated September 2, 1944: "Your telegraphic request for information concerning the court martialing of certain soldiers at this camp was referred to the headquarters. ... It prefers to withhold information for the present." But two reports prepared after the Walker-related incidents by the Army Inspector General's Office hint at the military's response. The so-called Burney Report concludes: "The best solution is to confine the organization to the limits of its regimental area and deprive it of all privileges until such time as it will disclose its real troublemakers." While the Peterson report concludes: "In light of the recent riotous conduct of the 364th Infantry, vigorous and prompt corrective action was necessary in order to place this regiment in such a disciplinary state that it would not again resort to mutinous conduct and to protect the lives of the citizens of Centreville and other innocent persons." Ridenhour interviewed black vets who remember being under this house-arrest and white soldiers who patrolled the cordoned-off area in jeeps and half-tracks mounted with .50-caliber machine guns. More letters intercepted by military intelligence and other Ridenhour interviews make reference to sporadic gunfire exchanges across the cordon line. The 1999 Army report does not mention armed patrols or house arrest. It refers to a disturbance in which members of the 364th disrupt a July 3, 1943 dance in the black section of camp. The disturbance was broken up by a battalion of the all-white 99th Division. "No one was hurt," reads the report. The rest of the summer is covered in a single sentence: "Training in the regiment continued through the summer of 1943 without incident." In September 1943, Col. Lathe Row of the Army Inspector General's Office studied the situation and concluded: "The presence of the 364th Infantry constitutes a threat to the normal peaceful conditions at Camp Van Dorn ... [and] should be transferred at an early date ... for overseas duty." Attached to the 1999 Army report is an appendix that indicates hundreds of soldiers (almost one-fourth of the regiment's authorized strength in the period) were transferred out of the troubled 364th Regiment to other segregated units. According to most 364th regimental documents, those troops not transferred left Camp Van Dorn by train December 26, 1943. After waiting a month or so at Fort Lawton, near Seattle, they embarked on three ships for the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. They served out most of the war spread out over 1,500 miles of desolate islands, sometimes eight to a Quonset hut. This is where things start to get especially confusing--and interesting. In the months

The main alphabetical roster of the 364th reconstructed by the Army in 1999 from personnel files not lost in the 1973 fire lists for each soldier the date he was "separated from service," a catch-all phrase covering all deletions from the payroll--through discharge, court martial or death. When these entries are re-sorted chronologically, a pattern emerges that appears to be at odds with the Army contention that there was little loss of personnel and that most soldiers served throughout the war. On average, about one soldier's name per day--from June 1943 through the end of the war--is dropped not just from the 364th's roster, but from the Army payroll as well. In 1999, the Army claimed it had accounted for all but 20 of the nearly 4,000 black enlisted men who served in the 364th during some period of time from April through December 1943. However, in a memo to filmmaker Greg DeHart in response to some of these apparent discrepancies, the Army was less than certain, explaining that faulty record keeping in the '40s, miscommunication about transfer orders and poorly copied records can account for the apparent conflicts. Even in 1943, the Third Army--which had responsibility for Camp Van Dorn--complained that the personnel reporting of the 364th appeared to reflect conflicting numbers. As Army spokeswoman Martha Rudd told DeHart in a memo: "You should understand that more than one part of the Army is involved in scheduling that affects units. The scheduling of training, unit movements and other unit activities in that era was not a centralized and always fully synchronized process." Regardless of the state of the documents the Army relied on, all that is accounted for are records of these men, not the men themselves. When the Army sought to interview by phone living members of the 364th, they turned up only 116 by the time the report was issued--and contacted only half of them. Of course, death by natural causes in a group this old would explain much. But when DeHart hired a private investigator to run computer traces on some members of the 364th named in 1943 intelligence files--37 out of about 200 "troublemakers"--the investigator reported a common response: "No records found for your subject." Some living soldiers were traceable. But when contacted by DeHart, some denied that they were ever in the 364th. A few initially agreed to be interviewed about violence at Camp Van Dorn, but then declined. The Army report published summaries of interviews with a dozen members of the 364th, who generally support the no-massacre position, though it is unclear when they were with the unit. DeHart interviewed one white officer of the 364th who says racial tension was high, but there was no big shoot-out. Two black enlisted men say they have no knowledge of such a conflagration, but one thinks he may have participated inadvertently in altering key documents, and the other was the victim of a secret court martial. The Army report raised more questions than it answered. Internal contradictions drew attention to possible errors in the government investigators' source material. For example, in the report's appendix that claims to be a complete accounting of the enlisted men in the 364th, Pvt. William Walker is listed as "separated from service"--off the payroll--on May 15, 1943. But Walker was shot and killed in uniform near the Camp Van Dorn gates two weeks later on May 30. Dozens of these kinds of discrepancies have emerged. Still, the report's failure to achieve the 100 percent accuracy initially claimed should not be taken as an indication that the allegations are true, only that the mystery continues. There are thousands of government documents in the National Archives--and some private collections--that may yet shed light on what happened at Camp Van Dorn. But many records, like those of the Office of Defense Transportation and the Merchant Marine, have been destroyed. Witnesses may be even harder to come by. Men still alive who served in World War II are now in their seventies and eighties. Increasingly, family members of both black and white soldiers are exploring the pasts of men who rarely, if ever, shared their military experiences. Those whose fathers had ties either with black combat regiments or those white units allegedly involved in violent incidents––like the 63rd and 99th divisions––are using their status as next-of-kin to obtain otherwise private military personnel files. But most Americans do not know what unit their relatives served in. And in the case of the 364th, transfers in and out of the regiment and redesignations (starting the war as the 367th, ending it as the 80th and 81st) has made tracing soldiers next to impossible. Certainly, the idea of a single massacre of dozens, let alone more than a thousand, soldiers in one unit at one base on one day, and a subsequent cover-up lasting almost 60 years, strains credulity. However, aspects of history can be hidden for generations. Historians and journalists have come to accept that legends sometimes can be keys to society's worst traumas. The white riot that leveled Tulsa's black community in 1921--and left as many as 300 dead--was a whispered myth until this year when a state commission acknowledged the overwhelming evidence and recommended reparations for victims' families. The level of racial violence in the military, the intensity of racial hatred and the willingness of elements of the Army to discriminate against blacks trying to serve their country is a disgrace that is gradually coming to light. Perhaps further research will show the worst violence at Camp Van Dorn and other bases occurred at the hands of civilians, not Army personnel. One army study, "The Treatment of The Negro Trainee," which was written months after the 1943 summer of violence and recently declassified, concludes: "There are a few cases where it appeared that the army officers deserted the men and left them to the mercy of civilian attackers." Or perhaps the "troublemakers" were disappeared into a maze of secret court martials, open-ended "disciplinary" internments and dishonorable discharges. Col. J.M. Roamer, director of Military Intelligence, wrote in an October 9, 1944 memo: "It is known that there are large numbers of Negro soldiers who are now awaiting discharge in camps where trouble has occurred. ... The discharge ... should be accelerated." Much work remains to be done. Geoffrey F.X. O'Connell's work is supported by a grant from The Fund for Investigative Journalism. Ron Ridenhour's investigation was supported by a grant from the Alicia Patterson Foundation. New Orleans attorney Mary Howell has assisted O'Connell in furthering his investigation. O'Connell can be reached at gfoconnell@aol.com.

|