|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

The road to the Killing Fields is narrow and pot-holed. But on a recent steamy Sunday afternoon it is deserted, so the drive goes quickly from the capital, Phnom Penh, about 10 miles to the southeast. The temperature exceeds 100 degrees, so the fields, which sit on a plateau some 40 feet above an adjacent rice paddy, seem cooler than the land below. For a time the fields are empty, save for a few children who beg for money and a woman selling drinks. Then a Korean tourist arrives, followed by a group of young Buddhist monks, heads shaved and orange gowns swaying as they move from one open grave site to another. The monks are praying over the grave, but they are among the few in Cambodia who

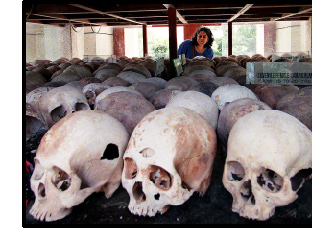

At the Killing Fields, there is no museum, only an open-air exhibit with three poster-size descriptions of this death camp, which was the final destination for prisoners detained and tortured in Pol Pot's Security Prison 21. More than 17,000 people are believed to have been executed in these fields, and the remains of half of them have been dug up. In the lone memorial on the site--a narrow pillar rising above the center of the fields--hundreds of skulls are visible, an odd testament to the dead. The skulls are piled high in a narrow, glass-enclosed case, but at the base there is an opening so that a visitor can handle the skulls or even carry one off. This casual, almost frivolous presentation of the remains does not go unnoticed. Indeed, the skulls merit more debate among Cambodians than do the acts of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. Buddhists prefer to burn their dead, and certainly don't wish to display the bones of loved ones, so the memorial raises the ire of many. The government recently promised to review the situation, holding open the possibility that the skulls will be properly disposed of and the memorial made more dignified. That the skulls of the Killing Fields draw more discussion than meting out a rough justice to the Khmer Rouge killers highlights Cambodia's predicament. The country's prime minister, Hun Sen, is a former Khmer Rouge commander who switched sides in the late '70s, when Vietnam turned its neighbor into a client state. In 1998, Hun Sen claimed victory in national elections, in a plebiscite that validated his coup a year earlier. The United Nations, which is the largest donor to this impoverished country of about 10 million people, has insisted for years that Cambodia hold war crimes trials. Though Pol Pot is dead, a few senior people in his government are still alive, as are thousands of the Khmer Rouge's rank and file, some of whom only laid down their arms in the past few years. The United Nations has given Hun Sen's government broad influence over these trials, though it wants some of the judges to come from other countries. Afraid of being judged by outsiders and facing the prospect of igniting a national debate over who did what to whom during the Pol Pot years, Hun Sen has refused to launch the tribunal. What looks like foot-dragging to the international community is considered by Cambodia's elite to be rational caution. "The trials will occur, in time, but the details are too important to get wrong," says Om Yentieng, one of Hun Sen's advisers. The same frustrating caution can be seen wherever matters of human rights arise in Cambodian life. Even victims of the Khmer Rouge--practically the entire Cambodian population over the age of 30--remain silent. One recent evening two married couples dine in a seafood restaurant across the road from the Mekong River, which cuts through Phnom Penh. The night air is refreshing, and talk turns to their childhood when each was forcibly removed from their homes by Pol Pot's soldiers. Sent to an unfamiliar rural area, they were compelled to scratch out a meager living from the land, always fearing that they would be killed after dark for some insane crime like speaking a few words of English or admitting that one had worked as a teacher. Today these four people each work for a foreign aid agency, earning good salaries and enjoying the fragile peace. One of the two women, who is studying for a master's degree and works full time, recalls that once, during a morning walk in the Pol Pot years, she found a stack of children's bodies, all dead. She hurried back to her family's camp and reported what she had found. Her parents' reaction still disappoints her. "Don't say anything," they told her. "Be quiet." These words are a metaphor for contemporary Cambodia, a society that tried too hard to ignore its past. Now herself a mother of two, this woman perhaps still carries the guilt of doing nothing, of saying nothing to protect herself. Writ large, Cambodia is a silent country, bereft of grief or reconciliation. Forget about justice or settling scores. These four Cambodians, and countless more who harbor grievous memories of a national bloodletting, have not the opportunity, or even the fearlessness, to merely stand and speak about what happened around them. "That will take another generation," says Kassie Neou, director of the Cambodian Institute of Human Rights. Because the Cambodians are still silent about their national shame, the commitment to a culture of rights and obligations remains weak here. Bribery is rampant. The army, still the most powerful institution in the country, dominates an array of cash businesses from logging to prostitution to drug smuggling. And political violence continues. A U.N. report, issued earlier this year, cited three murders last year of political activists. The United Nations also has found widespread evidence of torture by Cambodian police, reporting that 19 percent of prisoners claim to have been tortured in police custody and 2 percent claim to have been abused in prison. Often victims are too afraid to file complaints, and those who do complain suffer intimidation. In such a climate, elections can make a mockery of democracy. Under pressure from

Questions about Hun Sen's past as a Vietnamese puppet in the '80s, and his earlier support for Pol Pot, stops the United States from giving direct aid to the Cambodian government. Neou, whose own nonprofit group receives money indirectly from the U.S. Congress, understands the concerns of the American government. Hun Sen is no democrat. Yet Neou complains that the United States can do more. "When I say the U.S. should fully engage, I don't mean it should give a blank check to a corrupt group," he says, referring to Hun Sen and his cronies. Tortured by the Khmer Rouge (his crime was knowing how to speak English) and harassed by Hun Sen (his girlfriend was murdered in the 1998 campaign), Neou thinks the United States has a continuing debt to Cambodian reformers if only because of the American decision to widen the Vietnam War to include his country. Nixon's secret bombing and a U.S. invasion further destabilized a Cambodia already under pressure from Vietnamese Communists, setting the stage for the Communist victory in Vietnam, and for the Khmer Rouge seizure of Cambodia in 1975. "We hoped the Americans would protect us and they ran away," Neou says. Now the Cambodians are a people arguing not over how to hold a

kind of national day of reckoning, but what to do with the sun-bleached

skulls of the dead. Even this debate concerns only the elite, however.

On the recent broiling Sunday, as the Buddhist monks pray in the

Killing Fields, a woman clears brush with her machete in the rice

paddy below, singing in a sweet voice that can be heard far in the

distance. G. Pascal Zachary lives in London and is the author of The Global Me: New Cosmopolitans and the Competitive Edge.

|