|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

A.I.: Artificial Intelligence

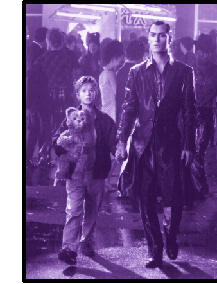

We fade in on huge churning waves, not a bad place to start: Steven Spielberg's A.I. pegs our end of days as waterlogged, with whole cities drowned under melted icecaps. It's the future and people now live in places like New Jersey--comfortably, in fact--thanks to science: Robots fill the void imposed by ecological disaster and strict sanctions on pregnancy. That's a lot of doom and zoom to be riding in on those cresting waves, and you brace yourself for the chop--just as Spielberg must have when he picked up this project from the late Stanley Kubrick, who, insiders say, secretly obsessed on its finer points for decades. But Spielberg, as toned and well-positioned as he is, just can't surf these waves; they might have even thrown the master. At its essence a retelling of the lost-boy Pinocchio story bathed in a meticulously imagined high-tech universe, A.I. has the overpowering taste of a dense French reduction left to stew for too long; it's so saturated with baroque detail and curly-cue plot extensions that you choke on the richness. It's like a million hours spent playing with the same toy. This is not the typical problem that sinks most summer blockbusters, that mysterious

Someone must have thought this was a good idea, maybe Spielberg himself, though his fulfillment of A.I. strikes me as duty as much as tribute. (There may have also been guilt: At one point he agreed to a formal collaboration with Kubrick but extricated himself after a month or so of intense transatlantic faxing.) At any rate, A.I. is certainly the most expensive honor ever paid a 90-page treatment, itself based on a one-gag short story by sci-fi author Brian Aldiss called "Supertoys Last All Summer Long," published 30 years ago and expanded over time by other writers, primarily novelists Ian Watson and Sara Maitland. Whatever spark was there though, holding Kubrick's interest for 25 years and burning unspeakable amounts of development money, will remain a mystery, now even further obscured by Spielberg's personalized version of the material. (The rambling screenplay is his first since Poltergeist.) But how could it not be? Kubrick, more than anyone else, depended on his own eye and stylized remove for his work's transcendence. O.K., so A.I. isn't a masterpiece rescued from an untimely death. It's here, though, and if hosannas aren't exactly in order there's certainly a lot of captivating whiz-bang to process, starting with the slightly menacing first scene--a robotics lecture given by William Hurt, who calls on his company to create a "mecha" who can love. It's an erudite chamber of the gods: self-satisfied with their progress and quick to applaud. (Hurt seems too wan a presence for the required arrogance; it's a part that calls for one of those plummy scientists from A Clockwork Orange.) Not five minutes in and we're already at a meta moment, where the creation of robot life can be swapped for the creation of cinema: Spielberg prevails (of course) as the benign god of what we see here--dramatically lit scientists with good intentions hesitating at moral quandaries--over what would have likely played as all-too-human buffoonery in the lapsed church of Kubrick. Suddenly it's 20 months later and their experiment is a reality. Enter David (Haley Joel Osment), a serenely beautiful child stepping tentatively into his adoptive parents' foyer. Osment's debut, so haunted and intuitive in The Sixth Sense, heralded a talent unseen since the lankier days of Jodie Foster, and he's clearly the real deal. With A.I., he has applied himself to a plasticine weirdness that would be a challenge to any actor, masking layers of expressiveness under artificially designed wraps. He's almost too perfect when he calmly asks, "Would you like me to go to bed now?" (The question is certainly a first in the history of child-rearing.) Spielberg stretches out in this initial section, and you might be surprised by how far he strays from familiar ground, leaving behind the picture of idyllic family life for some sharp commentary. David gives his owners the creeps, jolting them to nervous glances at the dinner table after a pre-programmed explosion of laughter at the sight of a hanging spaghetti strand. It's an expertly timed exchange, free of dialogue--a sly gloss on a saccharine, take-a-photo moment. Elsewhere, Spielberg is provocatively dark, especially after the couple's real son, Martin, returns home from a cryogenic deep-freeze in which he was suspended while awaiting a cure for his disease. He soon becomes a nasty rival, spurring David to self-mutilation and competition; he even forces their teddy bear (itself an ingenious robot with the clipped adult voice of a Joe Friday detective) to choose between them. There's a built-in irony to these brothers, the sickly Martin with his motorized leg braces and David, his durable but disposable surrogate who at one point stares blankly from the bottom of a swimming pool, forgotten in a panic that attends only to flesh-and-blood emergencies. A.I. teases us with a whiff of greater dimensions--something to do with human fallibility, a quest for perfection only attained in the making of perfect things. But in striving for that kind of cynicism (so natural to Kubrick, who breathed bleaker air), Spielberg sweats himself into uncomfortable shrillness. For all his fluidity, he's just no good at metaphysics. Thus Martin becomes a tiny terror and David a saintly unfortunate soul, impossible not to love. Worse still are the parents, set up strictly for easy contrast: Monica is an unnaturally fickle mother, exposing and closing her heart to David like a shellgame hustler (Frances O'Connor has one quiet, overwhelmed moment looking in the mirror that hints at unexplored depths); Henry (Sam Robards) goes from a can't-we-keep-the-puppy earnestness to fear and callousness in between edits. So when Monica invites David for a drive in the country, we already know what's in store for him; the archetypal abandonment in the woods has a shamelessness to it ("I'm sorry I didn't tell you about the world," she says, fleeing) that obliterates whatever critical distance remains. David may still be a replaceable product, but his heartwrenching pleas ("I'll be so real for you!") make that status almost an afterthought. So why introduce high-concept underpinnings in the first place, given the cost of parts? It's right around now--after Spielberg has hammered David into his kind of robot, adorable and misunderstood--that A.I. becomes a dangerously innocuous affair. Determined to become a real boy and regain his mother's love, David wanders across a pile of robotic carnage, limbs and jaws jutting out like Holocaust photography. This scene and his subsequent captivity at a "flesh fair," where robots are chainsawed and melted down for the entertainment of screaming hordes in bleachers, are as nightmarish as anything Spielberg has ever attempted, brutal and visceral as Schindler's List. Their success, though, relies on the transference of robots into persecuted outsiders: wandering mechanical Jews flung into tragic circumstances. It all seems a bit easy, given this project's pedigree. Robots are people too, it says (and thanks for the tip, Steven), but this must surely be a retreat from the indictment Kubrick was likely planning. "They made us too smart, too quick and too many," is the most telling line, spoken resignedly by Jude Law in a slick turn as a lover robot on the run; greater stuff of fate and folly was definitely in mind. But Spielberg's sticking with Kid A: airless set pieces pile up long after any quest for a Blue Fairy should have reasonably ended, finally propelling us to the submerged skyscrapers of Manhattan and a properly Kubrickian coda thousands of years later. John Williams' score swells (what else does it know how to do?) and one ultimately realizes that someone's played a big joke on poor David. Was it the scientists who programmed him to love a monster mom? (And why can't the super-advanced robots who greet him on the other side of an ice age help him out with that little bug?) Or was it Spielberg who programmed us to respond so helplessly to a machine in child's clothing? To say that A.I. ends in a dreamlike vacuum of self-absorption may be putting it too bluntly: Spielberg puts all his chips on his young lead--now the only "human" in sight--and we're dragged down into a weird oblivion of Oedipal bliss, uncomfortably close in tone to a golden-hued coffee commercial. Call it a draw. A.I. never does truly mesh its two artistic

sensibilities as some critics are gushing--it's more like mash.

(Or mush.) Kubrick's hundreds of sketches and notes are the real

artificial intelligence here, implanted in a filmmaker whose triumphal

moments--on the shark boat or making mystical mountains out of mashed

potatoes--have risen above thought to pure kinetic pleasure. If

you smell burning wires, it's due to intellectual overload. I fear

this new sentient Spielberg: He is at once our greatest mass communicator

and our least analytical. Only a snob can dismiss his work outright;

only the patronizing can call A.I. his breakthrough.

|