|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||||||

|

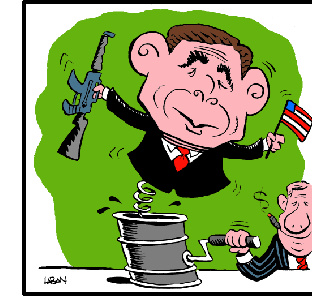

After only a few months as president, George W. Bush shocks visiting Indian Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh by calling him into the Oval Office for an unexpected chat. After years of supporting Montenegro's independence from Serbia, Bush suddenly reverses American policy and adopts a hostile attitude toward the country after it freely elects a pro-independence government. Vice President Dick Cheney uncharacteristically takes an interest in Bangladesh, one of the world's poorest countries. Shortly after becoming secretary of state, Colin Powell arranges an April peace summit between the presidents of Azerbaijan and Armenia. The peace talks, held in Key West, are not even interrupted by the capture of a Navy spy plane and its crew by China. These sudden changes in foreign policy did not arise from any altruism on the part of the Bush team. Instead, they are emblematic of the immense power that Big Oil now exercises over Washington's foreign policy apparatus. And nowhere is this more apparent than in the respective relationships that Bush and Cheney have with two energy industry magnates--Bill Gammell of Cairn Energy and Steve Remp of Ramco Energy. Both companies are headquartered in Scotland. Dubya's relationship with Bill Gammell has a historical precedent. In 1952, after his

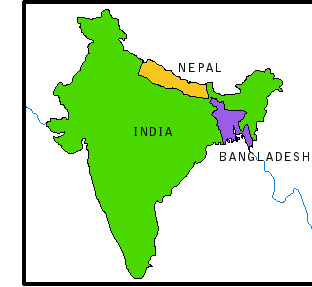

Bill Gammell, whom Dubya calls "Billy," is a bona fide "FOW"--friend of 'W'--and their relationship dates back to 1959, when a teen-age Bush spent the summer at the Gammell family's Scottish estate. That was Dubya's first trip to Europe. Bush again traveled to Scotland in 1982 when he needed Billy to ante up some cash for his fledgling Arbusto Energy Company in Midland, Texas. Billy was one of 50 original investors who sank some $3 million into the enterprise. Arbusto soon fell on hard times (though Bush made millions through a series of bailouts and sweetheart deals). Billy and the other investors got back just 20 cents on every dollar of their investment. Yet Bush returned to Scotland in 1983 for Billy's wedding. These visits were to leave an indelible mark on his worldview. Unlike Dubya, who seemed to have the reverse-Midas touch when it came to the oil business, Billy Gammell struck pay dirt. In 1999, his Cairn Energy found oil off the west coast of India in the Gulf of Cambay--a lucrative addition to the company's already sizable natural gas interests in Bangladesh and oil wells on the Indian mainland. So when Dubya called the Indian foreign minister into the Oval Office, chances are good they were not discussing the humidity in New Delhi. One of Bush's main political backers, Enron, is expanding its operations to India and is already running a privatized electrical distribution system in Bombay. And the shadow of Dick Cheney could not have been very far from that meeting. Cairn

Bush and Cheney's interest in India and Bangladesh has coincided with concern about a growing Maoist rebellion in nearby Nepal. U.S. military leaders--including Adm. Dennis Blair, commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific--have called for increased American military support for Nepal's armed forces in putting down the insurgency. In May, Army Sgt. Maj. Jack Tilley told the House Armed Services Committee that the United States had troops in Nepal, but he did not elaborate on their mission. American military intervention on the Indian subcontinent is part of Blair's pet project called the Multinational Planning Augmentation Team, or "Tempest Express," which seeks to put the U.S. military in charge of "peacekeeping" and "crisis management" exercises in Asia and is particularly focused on military-to-military links with Nepal and Bangladesh. Nepal's King Birendra, to the chagrin of Nepal's armed forces, had wanted to negotiate with the Maoists and avoid a bloody military confrontation. But in June, the reportedly drunken and enraged Nepali crown prince allegedly gunned down the king, queen, his two siblings and several high-ranking royal advisers before turning the gun on himself. Although Nepal's government stands by this explanation, much of the country's population suspects a wider conspiracy. An American human rights official working in Kathmandu disclosed, on the condition of anonymity, that the new king, Gyanendra, has maintained a long-term relationship with the CIA (an organization with a long history of "offing" leaders around the world, especially where U.S. economic interests are at stake). Not surprisingly, Gyanendra supports taking a much firmer line with the Maoists, a position welcomed by the Pentagon, Langley and, naturally, the nervous Western oil companies that are increasing their profiles and profit margins on the subcontinent. A Maoist Nepal might encourage similarly minded rebels, such as the Maoist Naxals who operate in six neighboring Indian states, and other leftist guerrillas in Bangladesh and Burma--a nightmare scenario for risk-wary oil and natural gas investors. The Indian Naxals, like their comrades in Nepal, have publicly claimed that the Nepali regicide was the work of the CIA and India's intelligence service. But such allegations have not just come from the rebels. Former high-ranking U.S. and Canadian intelligence officials who have been in contact with the Nepali expatriate community in North America quietly have confided that there is definitely "something" to allegations of U.S. intelligence involvement in the Kathmandu massacre. While his relationship is not as close as Gammell's with Dubya, Ramco's Steve Remp

In 1994, Ramco partnered in the Azerbaijan operation with Pennzoil, a company that was created when South Penn Oil Company was bought by Dubya's daddy's Zapata Petroleum Company (which itself had been launched with the help of a $50,000 investment from James Gammell). In 1999, PennzEnergy company--the new incarnation of Pennzoil--was bought by Devon Energy of Oklahoma City. Although Ramco has sold its concessions in Azerbaijan to Amerada Hess (directors of which have included Bush I Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady), Devon continues to play an important role in oil production in the Caspian fields. Devon too has important links to the Bushes. A former member of its board is Brent Scowcroft, national security adviser to Bush the Elder. And Devon President J. Larry Nichols was an outspoken critic of the Clinton administration's environmental policies, which he claimed hurt the energy industry. Not surprisingly, he was also an early donor to the Bush campaign, and, according to politicalmoneyline.com, he and his wife have donated thousands of dollars to GOP candidates over the past several years. These do not count the contributions to the GOP of Devon's own political action committee, officially registered in the midst of Bush's bruising primary battle with John McCain. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the Devon PAC gave $16,200 to GOP House and Senate candidates in the last election, but only $1,500 to Democrats; and in 1999, Devon contributed $20,000 to the Republican National Committee. The interests of Devon and other U.S. oil companies involved in Azerbaijan are championed by the U.S.-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce. Its former co-chairman is Richard Armitage--an Iran-contra figure who was accused by Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh of having detailed knowledge of the 1985 shipment of Hawk missiles to Iran while serving as an assistant secretary of defense. Armitage is now deputy secretary of state and Colin Powell's chief adviser. No wonder Powell did not waste any time in arranging the Key West peace talks between Azerbaijan's President Heydar Aliyev and Armenia's President Robert Kocharian. Since the two countries became independent after the collapse of the Soviet Union, they have been fighting over the Azerbijani-controlled but Armenian populated enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh. A bloody war lasted from 1992 to 1994 until a cease-fire was negotiated by Russia. The further development of trans-Caucasus oil pipelines cannot occur until the troublesome problem of Nagorno-Karabakh is settled. The importance of settling the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict to the Bush administration was apparent in comments made at a March 30 State Department briefing moderated by spokesman Philip Reeker. "In the 10th day of the Bush administration, President Bush dealt directly with this question," he said. "In the 10th week of the Bush presidency, we're having peace talks in Florida. There are communications at the presidential level, the level of the secretary of state, level of the national security adviser." It seems the Bush administration can be spurred into lightning-fast action when oil is

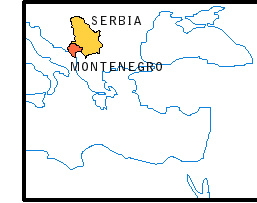

After his Azerbaijani success, Remp struck black gold again--this time off Montenegro's Adriatic coast. The Montenegro oil reserves may rival those found in the Caspian. Although Montenegro's government is pro-Western and has given Ramco a generous majority stake in the Adriatic oil profits, Djukanovic has been charged with corruption by some Western governments. As Arne Jan Flolo of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe told the New York Times last September: "Corruption is a time bomb ticking under the Djukanovic government." In April, State Department spokesman Richard Boucher signaled a change in U.S. policy toward Montenegro, saying that Washington now favors "a Democratic Montenegro within a reformed and Democratic Yugoslavia." That statement was a far cry from Madeleine Albright's earlier prodding of Montenegro to break away from Yugoslavia. The Bush administration apparently has decided to wait for a signal from the oil barons. Recently, senior Bush advisers held secret negotiations with Montenegrin trade officials. Who will give the oil companies the best deal? Djukanovic in the Montenegrin capital of Podgorica or Kostunica in Belgrade? That decision may ultimately determine whether a Montenegrin or Yugoslavian flag will fly over the small Adriatic republic. Much has been written and said about the influence of Big Oil over

the policies of Bush and Cheney on global warming, drilling in the

Alaskan wilderness, and their opposition to capping energy prices

in California. Yet such is the power of the industry over the Bush

administration, that Big Oil may influence, if not actually determine,

how international borders are drawn, which leaders remain as heads

of state and government, and what countries sit as members of the

United Nations. Apparently, that's what $26 million in political

contributions (the amount Big Oil gave to Republicans during the

last election) can buy. Wayne Madsen is an investigative journalist based in Washington. He is the author of Genocide and Covert Operations in Africa 1993-1999, an exposé of recent U.S. involvement in inter-ethnic warfare in Africa.

|