|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

Things go missing. It's to be expected. Even at the Pentagon. Last October, the Pentagon's inspector general reported that the military's accountants had misplaced a destroyer, several tanks and armored personnel carriers, hundreds of machine guns, rounds of ammo, grenade launchers and some surface-to-air missiles. In all, nearly $8 billion in weapons were AWOL. Those anomalies are bad enough. But what's truly chilling is the fact that the Pentagon has lost track of the mother of all weapons, a hydrogen bomb. The thermonuclear weapon, designed to incinerate Moscow, has been sitting somewhere off the coast of Savannah, Georgia for the past 40 years. The Air Force has gone to greater lengths to conceal the mishap than to locate the bomb and secure it. On the night of February 5, 1958 a B-47 Stratojet bomber carrying a hydrogen bomb

The Pentagon recorded the incident in a top secret memo to the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. The memo has been partially declassified: "A B-47 aircraft with a [word redacted] nuclear weapon aboard was damaged in a collision with an F-86 aircraft near Sylvania, Georgia, on February 5, 1958. The B-47 aircraft attempted three times unsuccessfully to land with the weapon. The weapon was then jettisoned visually over water off the mouth of the Savannah River. No detonation was observed." Soon search and rescue teams were sent to the site. Warsaw Sound was mysteriously cordoned off by Air Force troops. For six weeks, the Air Force looked for the bomb without success. Underwater divers scoured the depths, troops tromped through nearby salt marshes, and a blimp hovered over the area attempting to spot a hole or crater in the beach or swamp. Then just a month later, the search was abruptly halted. The Air Force sent its forces to Florence, South Carolina, where another H-bomb had been accidentally dropped by a B-47. The bomb's 200 pounds of TNT exploded on impact, sending radioactive debris across the landscape. The explosion caused extensive property damage and several injuries on the ground. Fortunately, the nuke itself didn't detonate. The search teams never returned to Tybee Island, and the affair of the missing H-bomb was discreetly covered up. The end of the search was noted in a partially declassified memo from the Pentagon to the AEC, in which the Air Force politely requested a new H-bomb to replace the one it had lost. "The search for this weapon was discontinued on 4-16-58 and the weapon is considered irretrievably lost. It is requested that one [phrase redacted] weapon be made available for release to the DOD as a replacement." There was a big problem, of course, and the Pentagon knew it. In the first three months of 1958 alone, the Air Force had four major accidents involving H-bombs. (Since 1945, the United States has lost 11 nuclear weapons.) The Tybee Island bomb remained a threat, as the AEC acknowledged in a June 10, 1958 classified memo to Congress: "There exists the possibility of accidental discovery of the unrecovered weapon through dredging or construction in the probable impact area. ... The Department of Defense has been requested to monitor all dredging and construction activities." But the wizards of Armageddon saw it less as a security, safety or ecological problem, than a potential public relations disaster that could turn an already paranoid population against their ambitious nuclear project. The Pentagon and the AEC tried to squelch media interest in the issue by a doling out a morsel of candor and a lot of misdirection. In a joint statement to the press, the Defense Department and the AEC admitted that radioactivity could be "scattered" by the detonation of the high explosives in the H-bombs. But the letter downplayed possibility of that ever happening: "The likelihood that a particular accident would involve a nuclear weapon is extremely limited." In fact, that scenario had already occurred and would occur again. That's where the matter stood for more than 42 years until a deep sea salvage company, run by former Air Force personnel and a CIA agent, disclosed the existence of the bomb and offered to locate it for a million dollars. Along with recently declassified documents, the disclosure prompted fear and outrage among coastal residents and calls for a congressional investigation into the incident itself and why the Pentagon had stopped looking for the missing bomb. "We're horrified because some of that information has been covered up for years," says Rep. Jack Kingston, a Georgia Republican. The cover-up continues. The Air Force, however, has told local residents and the congressional delegation that there was nothing to worry about. "We've looked into this particular issue from all angles and we're very comfortable," says Major Gen. Franklin J. "Judd" Blaisdell, deputy chief of staff for air and space operations at Air Force headquarters in Washington. "Our biggest concern is that of localized heavy metal contamination." The Air Force even has suggested that the bomb itself was not armed with a plutonium trigger. But this contention is disputed by a number of factors. Howard Dixon, a former Air Force sergeant who specialized in loading nuclear weapons onto planes, said that in his 31 years of experience he never once remembered a bomb being put on a plane that wasn't fully armed. Moreover, a newly declassified 1966 congressional testimony of W.J. Howard, then assistant secretary of defense, describes the Tybee Island bomb as a "complete weapon, a bomb with a nuclear capsule." Howard said that the Tybee Island bomb was one of two weapons lost up to that time that contained a plutonium trigger.

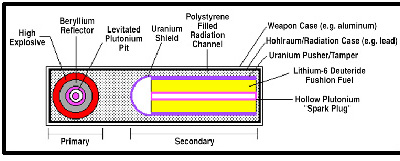

Recently declassified documents show that the jettisoned bomb was an "Mk-15, Mod O" hydrogen bomb, weighing four tons and packing more than 100 times the explosive punch of the one that incinerated Hiroshima. This was the first thermonuclear weapon deployed by the Air Force and featured the relatively primitive design created by that evil genius Edward Teller. The only fail-safe for this weapon was the physical separation of the plutonium capsule (or pit) from the weapon. In addition to the primary nuclear capsule, the bomb also harbored a secondary nuclear explosive, or sparkplug, designed to make it go thermo. This is a hollow plug about an inch in diameter made of either plutonium or highly enriched uranium (the Pentagon has never said which) that is filled with fusion fuel, most likely lithium-6 deuteride. Lithium is highly reactive in water. The plutonium in the bomb was manufactured at the Hanford Nuclear Site in Washington State and would be the oldest in the United States. That's bad news: Plutonium gets more dangerous as it ages.In addition, the bomb would contain other radioactive materials, such as uranium and beryllium. The bomb is also charged with 400 pounds of TNT, designed to cause the plutonium trigger to implode and thus start the nuclear explosion. As the years go by, those high explosives are becoming flaky, brittle and sensitive. The bomb is most likely now buried in 5 to 15 feet of sand and slowly leaking radioactivity into the rich crabbing grounds of the Warsaw Sound. If the Pentagon can't find the Tybee Island bomb, others might. That's the conclusion of Bert Soleau, a former CIA officer who now works with ASSURE, the salvage company. Soleau, a chemical engineer, says that it wouldn't be hard for terrorists to locate the weapon and recover the lithium, beryllium and enriched uranium, "the essential building blocks of nuclear weapons." What to do? Coastal residents want the weapon located and removed. "Plutonium is a nightmare and their own people know it," says Pam O'Brien, an anti-nuke organizer from Douglassville, Georgia. "It can get in everything--your eyes, your bones, your gonads. You never get over it. They need to get that thing out of there." The situation is reminiscent of the Palomares incident. On January 16, 1966, a B-52 bomber, carrying four hydrogen bombs, crashed while attempting to refuel in mid-air above the Spanish coast. Three of the H-bombs landed near the coastal farming village of Palomares. One of the bombs landed in a dry creek bed and was recovered, battered but relatively intact. But the TNT in two of the bombs exploded, gouging 10-foot holes in the ground and showering uranium and plutonium over a vast area. Over the next three months, more than 1,400 tons of radioactive soil and vegetation was scooped up, placed in barrels and, ironically enough, shipped back to the Savannah River Nuclear Weapons Lab, where it remains. The tomato fields near the craters were burned and buried. But there's no question that due to strong winds and other factors much of the contaminated soil was simply left in the area. "The total extent of the spread will never be known," concluded a 1975 report by the Defense Nuclear Agency. The cleanup was a joint operation between Air Force personnel and members of the Spanish civil guard. The U.S. workers wore protective clothing and were monitored for radiation exposure, but similar precautions weren't taken for their Spanish counterparts. "The Air Force was unprepared to provide adequate detection and monitoring for personnel when an aircraft accident occurred involving plutonium weapons in a remote area of a foreign country," the Air Force commander in charge of the cleanup later testified to Congress. The fourth bomb landed eight miles offshore and was missing for several months. It was eventually located by a mini-submarine in 2,850 feet of water, where it rests to this day. Two years later, on January 21, 1968, a similar accident occurred when a B-52 caught fire in flight above Greenland and crashed in ice-covered North Star Bay near the Thule Air Base. The impact detonated the explosives in all four of the plane's H-bombs, which scattered uranium, tritium and plutonium over a 2,000-foot radius. The intense fire melted a hole in the ice, which then refroze, encapsulating much of the debris, including the thermonuclear assembly from one of the bombs. The recovery operation, conducted in near total darkness at temperatures that plunged to minus-70 degrees, was known as Project Crested Ice. But the work crews called it "Dr. Freezelove." More than 10,000 tons of snow and ice were cut away, put into barrels and transported to Savannah River and Oak Ridge for disposal. Other radioactive debris was simply left on site, to melt into the bay after the spring thaws. More than 3,000 workers helped in the Thule recovery effort, many of them Danish soldiers. As at Palomares, most of the American workers were offered some protective gear, but not the Danes, who did much of the most dangerous work, including filling the barrels with the debris, often by hand. The decontamination procedures were primitive to say the least. An Air Force report noted that they were cleansed "by simply brushing the snow from garments and vehicles." Even though more than 38 Navy ships were called to assist in the recovery operation, and it was an open secret that the bombs had been lost, the Pentagon continued to lie about the situation. In one contentious exchange with the press, a Pentagon spokesman uttered this classic bit of military doublespeak: "I don't know of any missing bomb, but we have not positively identified what I think you are looking for." When Danish workers at Thule began to get sick from a slate of illnesses, ranging from rare cancers to blood disorders, the Pentagon refused to help. Even after a 1987 epidemiological study by a Danish medical institute showed that Thule workers were 50 percent more likely to develop cancers than other members of the Danish military, the Pentagon still refused to cooperate. Later that year, 200 of the workers sued the United States under the Foreign Military Claims Act. The lawsuit was dismissed, but the discovery process revealed thousands of pages of secret documents about the incident, including the fact that Air Force workers at the site, unlike the Danes, have not been subject to long-term health monitoring. Even so, the Pentagon continues to keep most of the material on the Thule incident secret, including any information on the extent of the radioactive (and other toxic) contamination. These recovery efforts don't inspire much confidence. But the Tybee Island bomb presents an even touchier situation. The presence of the unstable lithium deuteride and the deteriorating high explosives make retrieval of the bomb a very dangerous proposition--so dangerous, in fact, that even some environmentalists and anti-nuke activists argue that it might present less of a risk to leave the bomb wherever it is. In short, there aren't any easy answers. The problem is exacerbated

by the Pentagon's failure to conduct a comprehensive analysis of

the situation and reluctance to fully disclose what it knows. "I

believe the plutonium capsule is in the bomb, but that a nuclear

detonation is improbable because the neutron generators used back

then were polonium-beryllium, which has a very short half-life,"

says Don Moniak, a nuclear weapons expert with the Blue Ridge Environmental

Defense League in Aiken, South Carolina. "Without neutrons, weapons

grade plutonium won't blow. However, there could be a fission or

criticality event if the plutonium was somehow put in an incorrect

configuration. There could be a major inferno if the high explosives

went off and the lithium deuteride reacted as expected. Or there

could just be an explosion that scattered uranium and plutonium

all over hell."

Oops, You May Be Glowing It hasn't been an easy couple of years for the Department of Energy: contaminated workers, nuclear fuel rods misplaced (or lost), Hanford continuing to leak its immortal poison into the Columbia River, the Wen Ho Lee debacle, embarrassing contempt citations for the cover-up at Colorado's Rocky Flats, campaign finance scandals, contractors screwing things up royally then declaring bankruptcy and on and on. So for the past few months, the agency, anxious to be at the center of the Bush nuclear project, which runs the gamut from new nuclear power plants to another round of underground nuclear weapons testing, has been in full image-polishing mode. As part of this new PR rehab program, the DOE is allowing the public and the press into places that previously had been as difficult to access as Area 51. But when the secretive Savannah River nuclear site opened its gates for a public tour on July 9, things didn't quite turn out as planned. Savannah River, the big DOE waste dump/weapons complex in South Carolina, has had its own share of problems, including a massive spill of highly radioactive tritium into the Savannah River in 1991. Plant managers are trying to ease public anxiety enough so that the DOE can go forward with a Clinton-era plan to build a mixed-oxide fuel fabrication plant, a ludicrously dangerous scheme that involves the reprocessing of 36 tons of weapons-grade plutonium into fuel for commercial nuclear reactors. The 25-person tour of the site included reporters, environmentalists and neighbors of the plant. The tour was supposed to highlight the DOE's newly tightened operations. But it turned out to reveal just how dangerously slipshod the agency remains. After the tour group left the site's F-Area "tank farm," where the most highly radioactive waste is stored in underground tanks, Savannah River workers failed to monitor the group for radiation exposure. "This was an appalling breach of safety standards," says Tom Clements, head of the Nuclear Control Institute, who was on the tour. Savannah River managers admit the mistake, but blame it on a logistical screw-up. "We never intended for them to get off the bus there," says Rick Ford, a spokesman for the DOE. This is refreshingly candid, but far from reassuring. JSC |