|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

When my parents returned to India in the early '80s after living abroad for more than a decade, several friends and relatives thought they were half-crazy. After all, India then was perceived by many among its upper-middle class to be a socialistic, overly regulated country with very few economic opportunities for the better-off. How things have changed. The economic transformation that India has experienced in the past decade--and its

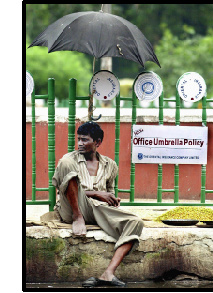

The size of this population--as defined by the number of people who can afford modern consumer conveniences--is in dispute. The most optimistic projections put this number at around 300 million, still less than one-third of the country's total population. But as many multinationals found out when they had to scale back their sales targets, this number is an exaggeration. Palagummi Sainath, the premier journalist covering poverty issues in India today, says that some surveys classify anyone who owns a wristwatch as middle-class. A visit to India's villages shows how thin the veneer of prosperity is here. I went with my family to a lake close to my home in the state of Uttar Pradesh. The lakeside village had a ramshackle building with hardly any facilities serving as the only primary school. The nearest high school and health care facility were miles away. The vast majority of the houses were flimsy constructions of thatch and straw. Kids walked around in a state that can, at best, be described as bedraggled. The village stood in stark contrast to the Crossroads shopping mall in Bombay, which I visited during the final days of my journey. The six-storied mall is full of clothing outlets, ritzy gift shops, swank bookstores and even a McDonald's. Many of the items available cost as much as several weeks' wages in the countryside. Places like Crossroads, still rare, were absolutely nonexistent when I was growing up in the '80s. India had a closed, protectionist economy with scarcely any foreign goods, especially consumer items, available (at least legally). My boarding school in western India even arranged a trip to Nepal, hundreds of miles away, with the essential purpose of enabling rich kids to purchase foreign goods such as Coca-Cola and Levi's jeans. Before the restructuring of the early '90s, restrictions on the operation of multinationals and tight regulation of the indigenous private sector meant that good jobs often were available only in the public sector, which occupied the "commanding heights" of the economy. During Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's heyday in the '60s and '70s, income taxes were very high on the extremely affluent, with the top marginal rate reaching as high as 97.5 percent (though less than 2 percent of the population actually pays the tax). Politicians rhetorically attacked the dominant economic classes, such as the landlords and industrialists (while privately seeking access to their funds and influence). Tariffs on imported goods were among the highest in the world. Travel abroad effectively was curtailed due to severe restrictions on foreign exchange. Television in almost the whole country was restricted to a single state-run channel, with a mix of propaganda for the ruling party, drab educational programming and some entertainment. The Indian upper-middle class perceived Indira Gandhi's economic policies as a straitjacket. They couldn't care less about the steady decline in the percentage of people below the poverty line under her tenure and that of her son, Rajiv Gandhi, from 53 percent in 1973-1974 to 34 percent in 1989-1990. Many among this segment also deemed insignificant that, in the '80s, India avoided hyperinflation and a Latin America-style economic crisis due to tight foreign-exchange controls and prudent economic management. Only when Rajiv Gandhi changed course did India experience a foreign-exchange crisis. India had started depleting its foreign exchange reserves in the late '80s, mainly to hard currency payments for a flood of imports and an increasing amount of foreign debt. Things came to a head in 1991, when the country only had enough foreign exchange left to pay for a few weeks of imports. The government went to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund for help, and consequently India opened up the economy and deregulated the private sector. Under Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, who assumed office that year, and his successors, restrictions on the multinationals and the private sector have been greatly relaxed. The current governing alliance, headed by the Bharatiya Janata Party's Atal Bihari Vajpayee, has continued the same policies. The public sector is being steadily, albeit slowly, dismantled. On April 1, the current administration lifted--one year ahead of schedule--quantitative restrictions on the import of a whole range of items to comply with World Trade Organization rules. The only major party that talks about class and redistribution anymore (although in muted terms) is the Communists, whose influence is limited to regional strongholds in Kerala and West Bengal. (There are parties formed along caste-based lines that talk about justice for the lower castes. But that's another story.) Conspicuous consumption, once kept in check for fear of income-tax raids, has become a status symbol. Income tax rates have been reduced dramatically. It's a cinch to get foreign exchange to travel abroad. Arcades and amusement parks have opened up in larger towns. And then there's television, which now offers a wide mix of programming, with Western shows (Friends, Baywatch), Indian versions of Western channels (CNBC, MTV) and Indian versions of Western programs (among the most popular shows in India today is the Hindi version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire). Prevalent throughout is a level of commercialism that makes American television seem staid by comparison. True, some problems affect the rich and the underprivileged alike, from crime and a decrepit infrastructure to extensive corruption. One stark illustration is the earthquake that struck India in late January: A number of apartment buildings in better-off neighborhoods of Ahmedabad, one of India's biggest commercial centers located hundreds of miles from the epicenter, collapsed due to shoddy construction, killing more than 700 people. Problems like these still compel many people to emigrate. But it has never been a better time to be prosperous in India. It's a different story for the poor, however. The past decade has been harsh for the roughly 300 million people living below the poverty line. And the divide between the haves and the have-nots has widened. This has occurred in spite of growth that averaged just below 6 percent during the '90s, an improvement over the less than 4 percent average during the immediate post-independence decades. "The gap between the upper-middle class and the poor since 1991 has never been seen since independence," says Sainath, whose articles on India's poor have been collected into the book Everybody Loves a Good Drought: Stories from India's Poorest Districts. "India's participation in globalization will result in deepening inequality." Some analysts, such as Jean Dréze, professor at the Delhi School of Economics and frequent collaborator with Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen, add that the '90s saw a deceleration in the improvement of a number of social indicators, such as infant mortality and life expectancy. According to a recent article in The Hindu newspaper by Professor Gita Singh of the Indian Institute of Management, this deceleration has come about due to policies carried out as part of the neoliberal agenda--such as stagnant public health expenditures, removal of price controls on essential drugs, and subsidizing private hospitals at the expense of public ones. The very fact that the current debate is about whether the restructuring has helped the poor--and not by how much--highlights the meager benefits the free market path has brought to the destitute. "Proponents of globalization say wait for 10 years," says Dilip D'Souza, a columnist for various publications. "But the poor can't wait. They have waited for 53 years. We have to have urgent measures to help them." The Indian elite views countries like Singapore and South Korea's orientation toward globalization and the free market as the model for success. Never mind that many of these countries placed primary emphasis on providing universal literacy and health care to their citizens, or that they often engaged in protectionist and interventionist policies, such as radical land reform. Also overlooked is the fact that the Indian state which has provided the most decent life for its people--Kerala--has done so with extensive vigorous state action, such as far-reaching land reforms, an extensive welfare-state apparatus and pro-union interventions in the labor market. Instead, many among the upper crust are calling for an Indian version of Reaganomics. "If some people do well, they'll employ other people, and the wealth will eventually trickle down, just as in the United States," said one of my wife's cousins, who works at Hong Kong Bank. "Government intervention has never made the poor rich anywhere in the world." The second, even more incredible thread that often runs through the thoughts of the comfortable is the notion of "blaming the victim." The poor are miserable because they have too many children, the reasoning goes. Once they start family planning and control their procreational urges, they'll be on their way to upward mobility. "The better off have always had this attitude toward the poor," D'Souza says. "But now it is respectable to say this." An official conceit, echoed by many among the prosperous, is that the boom in India's software-export business over the past decade is going to solve or drastically ameliorate India's problems, including poverty. While the software industry has grown by 50 percent annually in the past decade, this segment still contributes a paltry 2 percent to India's GDP. And the term digital divide has a radically different meaning in India: Only 22 people per 1,000 in the country have access to a telephone, while less than five in 1,000 have a computer. "The benefits of the information-technology industry to the poor will depend on the extent it is absorbed by the rest of the economy," says Krishna Raj, editor of Economic and Political Weekly, perhaps the publication providing the best in-depth coverage of socioeconomic and political trends in India. "The sector is 95 percent for export. It should be more oriented to the domestic economy." With the poor increasingly left to the whims of the market, there

is little chance that things will improve significantly for them

in the near future. As for the affluent, they are cheering the changes

since Indira Gandhi's days. Unlike the poor, they don't have to

wait for the results to trickle down. Amitabh Pal is the editor of the Progressive Media Project in Madison, Wisconsin.

|