|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Planet of the Apes First, a confession: I've got this thing for primates. Put one in a movie and I'm helpless. They always steal the screen, eschewing an actor's craft for something more natural, an animal ranginess--just like Brando. Should I recuse myself then from reviewing this new Planet of the Apes, which offers (in its first 10 minutes alone!) a tiny chimp piloting a spaceship and giving the opposable thumbs-up sign to his human crewmates? I think not. Really, I wanted to keep quiet about this. The higher mind would prevail, I privately

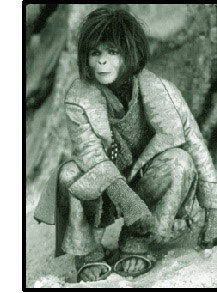

Seeing as we're not yet out of the jungle, you can pardon me for expecting Tim Burton's "reimagining" to rise above the customary fanfare spun around the revival of a once-profitable franchise. (Besides, Burton made a gloomier Batman than anyone could have hoped for.) Imagine my surprise to report that it's merely a fetish film for monkey lovers. It's a theme-park Planet made by people who loved the gag, those plastic snouts, but saw or heard no evil. Resultingly, little evil is spoken here, apart from a few jokey references to Barry Goldwater ("Extremism in defense of apes is not a vice!") and--wait for it--Rodney King. What the movie really wants to do is run, and run it does (on all fours) past the subtext as well as the text, which blurs by like signposts on a too-familiar road: the years ticking upward on a ship's dashboard, the crash landing, the chase through the ferns, the none-too-shocking revelation of the pursuers. Guess what? They're apes. It's a madhouse. All right, so you knew that already. So why not put these re-imagineers onto something more productive--like developing our castaway hero? Mark Wahlberg is a fine choice; he's been brave enough to slouch that underwear model's physique and make his whole face crack open when overwhelmed. (Could there have been a better Dirk Diggler?) But here, he's just as stranded as his astronaut: It's one of those boring, man-of-action parts, dumbed-down far beneath his abilities. Looking back, it's easy to mock Heston's strutting hauteur--and Apes was really his sun-tanned moment--but consider how crucial that arrogance was to the role's comeuppance as denigrated human pet and unwitting world wrecker, and you'll begin to grasp what Burton won't acknowledge. He actually thinks he can pull this off with plight sympathy alone, but the timidity backfires; Wahlberg is never allowed more than a get-me-outta-here grimace. He's got nothing to work with but genes. But apes are more fun anyway; they're so expressive here that you might not miss human evolution at all. It's the wittiest makeup work in years. (I was especially taken by the luscious dark wrinkles on the gorillas' faces.) The genius designer is Rick Baker, one of the last of the old-school artisans not yet replaced by a squad of computer programmers. (He did those sprouting claws in American Werewolf in London.) Actors don't have to transcend his plastic, furry architectures because they're already designed for great emotional transparency: Helena Bonham Carter makes a weirdly fetching "human rights activist" who falls for the man from the sky; Tim Roth is the snarling simian general hot for them both; a wheedling orangutan (Paul Giamatti) saunters off with the best lines and doubletakes. They're completely believable, and one begins to wish Baker could have done a little number on the distracting collagen-inflated moue of Estella Warren, this version's designated jungle babe in low-cut pelts. (You should know ahead that these native humans can talk, a revision that makes no sense when casting Maxim centerfolds.) We trek out to the canyoned Forbidden Zone, though not before a

ludicrous cameo by Heston himself, introducing--what else?--a gun

into the proceedings. Gorilla warfare soon becomes the order of

the day and you'll experience some palpable seat-shifting. But Burton

is its chief casualty; he's so much better at loners than phalanxes.

(He does get off one signature shot: a comically bleak toddler silently

weeping in her human dollhouse of a cage.) No remake would have

been deemed complete without a shockaroo ending--and this Apes

has its lulu, which I won't disclose--but it leaves behind the stink

of arbitrary mystification. Who needs a brain when you have all

that flying fur?

|