|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

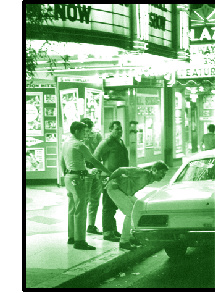

Illusion of Order: The False Promise On March 16, 2000, a team of three undercover narcotics officers working Midtown Manhattan held out for one more bust, hoping to round out the day's arrests at 10. For the setup, one of the officers played the user. He approached a black man standing outside a cocktail lounge: "You know where I can find some weed?" Offended at being taken for a dealer, the man told the undercover cop to get lost. Angry words escalated to flying fists. Another officer rushed in, gun drawn. A moment later, the man was dead. The officer who shot unarmed Patrick Dorismond belonged to the NYPD's recently hatched Operation Condor, which aggressively pursues misdemeanor drug offenders. (The unit shares its name with another notorious undercover operation--the U.S.-sanctioned hunt for South American dissidents during the '70s and '80s.) New York's Condor is but the newest incarnation of an "order maintenance" approach to policing that has dominated New York for almost a decade. Order maintenance--as old a concept as policing itself--was revived nearly 20 years ago by the much-lauded "broken windows" theory. In The Atlantic Monthly, criminologists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling set out their common-sense thesis that disorderly streets communicate a lack of control, emboldening criminals, distressing law abiders and plunging the community down a "spiral of urban decay." Broken windows is perhaps the most seductive criminal justice theory to emerge in

From the '70s onward, policymakers faced with social disillusionment and dwindling public resources increasingly abandoned the root-cause approach to crime prevention. By the late '80s, their cities plagued by delinquency and decrepitude, public policymakers seized upon the broken windows theory and its promise of a cure-all for crime. Yet there is no evidence that disorder actually causes crime, Harcourt argues, and policing it has proven at odds with democratic principles of civil liberty. The broken windows theory also marks a turn toward incorporating social meaning and norms into the classical model of criminology. According to "social norm" proponents, the "social meaning" of order dissuades would-be criminals by signaling that the community is in control and crime ill-tolerated. By dispersing loiterers, painting over graffiti and mending the proverbial broken windows, cities can control serious crimes such as homicide and rape. But police officers are not maintenance men or social workers. Order-maintenance policing may in fact cut crime, Harcourt says, but not through the mechanism of social influence. "It is somewhat jarring to uncover what appears to be a straightforward policy of aggressive misdemeanor arrests masquerading as a neighborhood beautification program or as an innocent phenomenon of social influence," he writes. Harcourt notes that Kelling himself has said that broken windows reduces crime "at least in part because restoring order puts police in contact with persons who carry weapons and who commit serious crimes." Under the guise of order maintenance, then, police cast a wider net for illegal weapons and drugs, ensnaring those with outstanding warrants and enlisting more informants in the process. Harcourt cites former New York Police Commissioner William Bratton's telling description of early subway sweeps as a "bonanza." According to Bratton, "Every arrest was like opening a box of Cracker Jack. What kind of toy am I going to get? Got a gun? Got a knife? Got a warrant?" Although this approach has led to the capture of some real criminals, a vast number of innocent people, such as Patrick Dorismond, are unavoidably enmeshed in the sweeps, stop-and-frisks and buy-and-busts that one NYPD officer referred to as "fishing expeditions." The New York State Attorney General has found that 7 to 10 people are stopped before the NYPD nets one arrest. Though some have attempted to distinguish between broken windows and zero-tolerance--indiscriminate arrests for minor offenses--Harcourt shows that there is little distinction. From the start, order-maintenance policing in New York City and elsewhere has emphasized sweeps, arrests and detentions. Unsurprisingly, these methods have swelled courts, jails and probation officers' caseloads. In New York, the mean streets have been painted blue with more than 40,000 officers, in rarefied units like Street Crimes and Condor, who puff up arrest statistics by busting panhandlers, prostitutes, peddlers, drunks, junkies and low-level dealers. After Dorismond's death, it was reported that 75 percent of Condor arrests were misdemeanors, and that misdemeanor narcotics arrests had increased by 68 percent over the previous year. In Chicago, under anti-gang and anti-narcotics loitering ordinances, police have arrested tens of thousands of people for just standing around. When police exercise discretion--true zero-tolerance is not really feasible--it is often at the expense of people of color, as numerous studies of racial profiling show. Indeed, broken windows criminalizes large swaths of the population--including who Wilson and Kelling call the merely "obstreperous or unpredictable" --making it easier for the rest of us to condone treatment of others that we would not accept for ourselves. Historically, disorder was annoying, but not criminal. John Stuart Mill's famous "harm principle" holds that "the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others." The broken windows theory has undermined this principle by asserting the harm of disorder. At the expense of civil liberties, Harcourt writes, the theory enforces "aesthetic preferences" rather than legal norms. Returning to Michel Foucault's Discipline and Punish, Harcourt relates this development to an earlier shift in the law from the criminal act to the criminal soul. Broken windows, he says, "focuses on the presence of the disorderly rather than on the criminal act. It judges the disorderly not simply by giving the individual a criminal record, and not simply by convicting the person, but by turning the individual into someone who needs to be policed and surveyed, relocated and controlled." Worse yet, Harcourt demonstrates through painstaking statistical analysis that the broken windows theory is just not supported by the data. The most frequently cited studies "proving" the theory at best establish a tenuous connection between minor disorder and serious crime--specifically, robbery. At worst, researchers have misrepresented their own data; studies show absolutely no causal relationship between disorder and crime. The most careful data show, by contrast, that both crime and disorder likely have deeper roots in structural disadvantage, disfranchisement and a lack of community cohesion. Harcourt's analysis shows that New York's crime wave had already begun to ebb before the quality-of-life initiative, and that there are plenty of other likely factors for the decrease--fewer males aged 18 to 24, more felons in prison for longer, an improved economy, less crack cocaine, and new computerized crime-tracking systems. Moreover, Harcourt notes that cities such as San Diego, which reduced misdemeanor arrests, also experienced sharp declines in street crime during the '90s. If it is doubtful that broken windows has been the mechanism behind

diminishing crime, it is clear that by targeting the "disorderly,"

the theory has fueled aggressive police practices that bear most

heavily on the dark, young and poor. While Manhattan's main drags

may seem cleaner and safer than they were a decade ago, off to the

side, in the neighborhoods and prisons and precinct houses, lurks

a larger disorder in the form of racial profiling, police brutality,

increased detention, expanded surveillance and the criminalization

of a greater share of our citizenry. Among the many casualties are

innocents such as the 26-year-old Dorismond, a security guard and

father of two young girls. "What we are left with today is a system

of severe punishments for major offenders and severe treatment for

minor offenders and ordinary citizens, especially minorities," Harcourt

writes. "We are left with the worst of both worlds." Megan Costello, a freelance writer based in New York City, can be reached at macello68@hotmail.com.

|