|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

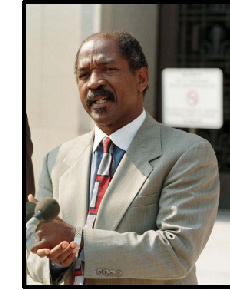

Charles Ogletree is no stranger to difficult legal battles. A Harvard Law School professor and eminent legal theorist, Ogletree counseled Anita Hill through the Senate hearings that inserted the phrase "sexual harassment" into the national lexicon. He has even defended the likes of Mafioso John Gotti and played a leading role in drafting South Africa's post-apartheid constitution. But Ogletree's next legal effort could easily prove his most challenging. In November, Ogletree announced the collective intention of a number of highly respected black lawyers to sue the U.S. government--as well as individuals and private companies who directly benefited--for reparations for slavery. "The focus is on recognizing the enormous impact of slavery," Ogletree says, "without necessarily figuring out what the remedy will be or how it will be dispersed." Joining him are some of America's most successful attorneys, including Johnnie

Since making the announcement, Ogletree has been keeping his usual hectic schedule, dividing his time between teaching, speaking and legal work. He and his associates rarely have spoken to the media about their intentions. When they do, they compare their efforts to the successful crusade of European Jews to gain reparations for past injustices. "When the Germans and the Austrians and the Swiss responded to the Holocaust, they not only acknowledged individual victims, but they also acknowledged the impact on greater communities," he says of the $8 billion reparations settlement which Germany, France and Austria, along with Swiss banks, recently agreed to pay Holocaust victims. "They took a responsibility as defendants, as a government, even though not every person in that society was responsible or culpable. This situation is in no material respects really different." As early as 1866, Congress passed a bill endorsing the procurement of 40 acres and a mule for every newly freedman. President Andrew Johnson vetoed it. Yet Ogletree and his associates have pulled the issue from the fringes of contemporary debate to the very heart of the American mainstream. Still, recent polls show as many as 75 percent of Americans are opposed to reparations. This despite the fact that, as Ogletree points out, blacks endured more than 250 years of legal slavery and 100 years of Jim Crow segregation. In fact, to Ogletree, 75 percent opposition is encouraging, and only further evidence that legal channels are the most appropriate for his cause. "We have always recognized the majority will but minority rights," Ogletree says. "And if popular will decided every moral issue we would not have the right of women to choose, we would not have the opportunity for people to vote and participate in society equally, we would not have constitutional protections for minorities, and we would not have limits to police power." But is the goal really practically attainable? Ogletree certainly thinks so. Perhaps a lifetime spent overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds has given him the wherewithal to believe so. Raised in the dusty railway town of Merced, California, the first of six children, Ogletree felt slavery's legacy firsthand. His father left school in the fifth grade and spent his life as an itinerant farmhand. Practically from the time he could walk, Ogletree picked fruit to help his family make a living. As long he could remember, whites and blacks remained on opposite sides of the tracks in Merced. Ogletree's exceptional grades in high school led his counselor to recommend that he apply to Stanford. Too embarrassed to admit that he'd never heard of the place, he told her he didn't want to go to school somewhere it was so cold, supposing the university was in Connecticut. But after arriving at the university in 1970, he didn't take long to adjust, graduating in three years with Phi Beta Kappa honors. It was at Stanford that he also found his calling, becoming the president of Stanford Students for the Defense of Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners. Ogletree went on to complete a master's in political science at Stanford and then attain a law degree from Harvard. He then worked at the public defenders office in Washington, widely regarded as the best in the country. While there, Ogletree gained acclaim for his near perfect record in the courtroom. With time, he wanted to teach, and in 1986, took a faculty position at Harvard. What may surprise many detractors who still don't take the reparations movement seriously is this: According to Ogletree, he and his associates already have plaintiffs and defendants in mind, though of course he won't discuss the details on the record. Legal action, he says, is imminent. "Before the year is out some important decisions should be made." Conscious of what is at stake, Ogletree knows that, if successful,

his pursuit of reparations could prove momentous. Ogletree calls

his push the first step toward redemption. "It's going to be confrontational,"

he says. "It's going to be divisive, but we can't really fully remedy

our problems of race by ignoring them." Alex Kellogg is a reporting fellow for The Chronicle of Higher Education.

|