|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

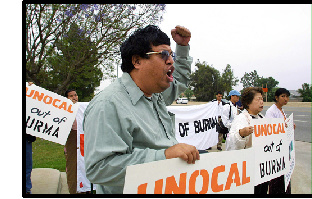

There may be no country with a worse record on labor rights than Burma, where the military regime regularly forces workers to toil on government and private projects for no pay. If the new global order can't act against such an extreme case, then there is little hope of effective protection of labor rights anywhere. The campaign to support the democratic opposition in Burma nevertheless has exerted significant pressure on the ruling junta, mainly by attacking corporate investment in Burma and sales of Burmese products. The drive for strong economic sanctions has the support of opposition leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi. In the '90s, U.S. supporters of Burmese democracy attacked companies that operated in Burma with demonstrations, newspaper ads, shareholder resolutions and embarrassment of corporate officers and directors, forcing corporations such as Amoco, Texaco, Pepsi, Disney, Ericsson and Levi Strauss to withdraw from the country. But some U.S. companies remain, most notably Unocal in partnership with France-based TotalElfFina. The screws tightened a bit more in 1997 when President Clinton issued an executive

After the sanctions, the regime needed new sources of income to supplement the cash generated by its two major exports--energy (oil and natural gas) and drugs, especially heroin. Many Southeast Asian governments, embracing Burma, have ignored its human rights violations. Capital has flowed in from Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Korea, especially into garment factories that military officials control. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, wages in these factories are as low as 4 cents an hour, the lowest-paid workforce in the world. Garment exports to the United States--which could have unilaterally set quotas as low as it wanted--rapidly expanded, hitting $412 million last year and probably close to $500 million this year, making the United States Burma's largest garment export market. Last year, the National Labor Committee, which has led many sweatshop fights, and the Free Burma Coalition exposed prominent brand names and retailers, including Kenneth Cole, Jansport, Nautica, Adidas and Ikea, whose products were made in Burma. With the glare of publicity, many of those companies promised to cut off all Burmese sources. Even Wal-Mart, which initially refused, made the pledge after revelations that one of its suppliers was a major druglord. But anti-sweatshop groups report that others--like the big May and Federated department store chains, Fila and Tommy Hilfiger--continue to buy from Burmese factories. Meanwhile, as some big name brands pledge to avoid Burma, Burmese products have flooded into bargain retailers like Ames and Costco. A bipartisan coalition in Congress, led by liberals like Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin but also including right-wing Republicans like North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms, is backing legislation that would ban all imports from Burma until there is significant progress on human rights, democracy and counter-narcotics action. Although there is little overt opposition to the ban, mainly from the apparel importers trade association, there is a lot of foot-dragging from even moderate Democrats "who favor trade over human rights," according to Simon Billenness, a leader in the Free Burma Coalition. The legislation was prompted not only by the soaring imports, but also by an unprecedented decision last year by the International Labor Organization to ask its members--which include governments, unions and businesses from most countries in the world--to review relationships with Burma and cease any activity that could abet forced labor. Although this first-ever ILO call for such concerted action was theoretically a step toward global enforcement of core labor rights, there have been few concrete responses. Indeed, many are weary of challenging the free trade regime. World Trade Organization Director Michael Moore admitted two years ago that his organization would do nothing about labor practices in Burma, a WTO member. And under the WTO, the European Union and Japan had earlier challenged a 1996 Massachusetts law, modeled on the anti-apartheid measures aimed at South Africa in the '80s, that prohibited state government purchases from companies doing business in Burma. The WTO never ruled on the challenge because the Massachusetts legislation, which had inspired several cities to pass similar laws, was overturned in the courts first. But legal advisers to the democracy campaigners suggest that states and local governments could pass other legislation, including calls for divestment by public bodies, such as pension funds, of stock in companies that do business with Burma. Los Angeles, Minneapolis and other cities, as well as the state of Massachusetts, have either passed such laws or are considering them. Meanwhile, students on many campuses are pushing for divestment or university bans on purchasing from businesses operating in Burma. Beyond the continuing publicity campaigns against various brands or stores like Suzuki (which has an assembly plant in Burma), Marriott (which has a partnership with a resort hotel in Burma) or Pottery Barn (which introduced a special line of Burmese baskets), groups promoting democracy in Burma, including the international labor movement, are pursuing both shareholder actions and lawsuits against companies. In 1996 two lawsuits, now partly consolidated, claimed that Unocal was liable for harm to Burmese citizens who were forced to work on its pipeline by the Burmese military, which was a partner with Unocal and provided security for the project. It was the first time that a corporation had been sued for human rights violations under the old Alien Torts Claim Act, which had been successfully revived to sue foreign governmental human rights abusers in U.S. courts. A California district court agreed to hear the case, and concluded that the evidence showed that Unocal knew about the use of forced labor and benefited from it. But the judge issued a summary judgment that Unocal was not liable, because the evidence did not show that it had control over the government. International Labor Rights Fund (ILRF) lawyer Terry Collingsworth, who argued one of the cases, believes that he will win an appeal now underway that argues it was only necessary to show that Unocal aided and abetted the military action and that, in any case, it should have been an issue for a jury to decide, not the judge. Meanwhile, the two cooperating legal teams--from ILRF and EarthRights International--also are suing Unocal for battery, unlawful detention, slavery and other abuses in California state court. The cases could cost Unocal well over $1 billion if it loses. Earlier this year, the AFL-CIO, the labor-linked LongView Investment Fund and the Maryknoll religious order sponsored shareholder resolutions at different companies, including Unocal, Citigroup, McDermott International and Halliburton. These resolutions typically asked the companies to guarantee that they are not involved in forced labor or violation of sanctions in Burma. Although none passed, they did win strong support in comparison to previous Burma-related resolutions. Such actions send a clear message that the high legal and political

risks of doing business with the junta could depress stock value

and corporate performance. But while supporters of Burmese democracy

put pressure on governments and corporations in the United States

and Europe, the military regime can still count on investment from

Asian neighbors, new foreign aid from Japan and aggressive marketing

of cheap Burmese goods by Chinese businesses. Despite government

talks with the opposition, there are no signs of progress toward

democracy or an end to forced labor. Now read Joshua Schenker's "Pariah Nation"

|