|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

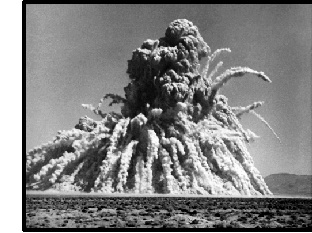

In the first few months of the Bush administration, international treaties have been falling faster than old-growth trees. The rebuke of the Kyoto global warming accord grabbed the headlines, but there have been a slate of others: the convention on small arms trade, the chemical and biological weapons treaty, the international ban on whaling, and the Anti-Ballistic Missile treaty. Now the Bush administration wants to end the moratorium on testing nuclear weapons and junk the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Bush fumed against the test ban treaty repeatedly during his campaign, alleging that it undermined national security. Since the election, Bush has remained stubbornly mute on his personal position on resuming nuclear tests. (The current moratorium on nuclear testing was put into place as a pre-election ploy by his father in 1992.) But Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and Vice President Dick Cheney have been less coy. Both have argued that the United States needs to resume nuclear testing to ensure the reliability of the Pentagon's nuclear weapons cache. This is an old canard. The only parts of the nuclear stockpile likely to deteriorate are

The purported rationale for the U.S. nuclear stockpile, which now totals some 12,000 nukes and 10,000 plutonium pits (or triggers), is deterrence. Coghlan suggests that the real interest of the testing faction isn't to assure reliability, but to shift to more tactical uses. "U.S. nuclear weapons are certainly reliable in the sense that they are sure to go off," he says. "The concern that the military has with reliability is that weapons are not only guaranteed to go off, but explode close to design yield. This is important not for mere deterrence, but for nuclear warfighting." One of the great myths of the Clinton era was that Clinton supported total abolition of nuclear testing. In fact, Clinton authorized a series of so-called subcritical nuclear tests and a number of other nuclear programs that quietly flouted the test ban treaty--which he simultaneously heckled the Senate for failing to approve. The Bush administration, of course, has no intention of seeking approval for the test ban treaty from the Senate, where it has languished for more than two years. But its top arms control negotiator, John Bolton, undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, has determined that the administration can't unilaterally withdraw the treaty from consideration. The Senate has two options: It can approve the treaty by a two-thirds vote, or it can send it back to the president for renegotiation through a simple resolution, which requires only a majority. Currently, 161 nations have signed onto the treaty, and 77 nations have ratified it, including the rest of NATO. For the treaty to go into effect, it must be approved by 13 other nations. The other holdouts include China, India, Pakistan, North Korea and Israel. But this renegade status doesn't seem to have deterred Bush in the least. Indeed, the president has loaded the top levels of his administration with full-blooded nuclear hawks, including Defense Department flacks Douglas Feith, Richard Armitage and Paul Wolfowitz, all of whom have railed against the limitations of the test ban treaty. The most fanatical of the brood may well be Jack Crouch, Bush's pick for assistant secretary of defense for international security policy. In the mid-'90s, Crouch, then a professor at Southwest Missouri State, wrote a series of articles attacking the test ban treaty and the testing moratorium. He also argued that the United States should deploy nuclear weapons in South Korea and consider using them against North Korea if they did not accede to U.S. demands to drop their nuclear and biological warfare programs. Crouch reiterated his support for nuclear testing and his opposition to the test ban treaty during his confirmation hearings before the Senate Armed Services Committee. "I think that considering the resumption of testing is something that the administration ought to consider," Crouch said. Consider it they are. Shortly after taking office, the Bush crowd heard from an advisory committee that had just completed a study on the "reliability, safety and security" of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. The panel was headed by John Foster, former director of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who now serves as an adviser to TRW, one of the nation's top defense contractors. The Foster group urged the administration to begin taking steps to resume testing as quickly as possible and to begin training a new crop of weapons designers who could develop "robust, alternative warheads that will provide a hedge if problems occur in the future." Even though most other nuclear scientists disagree, Foster, a protégé of Edward Teller, dismissed computer modeling as a substitute for real nuclear explosions. "There are a number of underground tests we can't reproduce," Foster told a gathering of weapons designers at the National Defense University in June. "We have these enigmas." For Foster the answer to every enigma seems to be a nuclear explosion. He argues that the U.S. nuclear arsenal is aging and growing ever more unreliable. The average age of nukes in the U.S. weapons stockpile is 18 years, which Foster claims is six years older than their intended design life. "They will be many times their design life before they are replaced," Foster said. "We have opened some of the warheads and found some defects that are worrisome." Using the Foster report as an excuse, in June the Bush administration instructed the

The move to truncate the readiness period for tests exposes yet another double-standard in the Bush administration's foreign policy. As the Pentagon moves ever closer toward resumption of testing, Secretary of State Colin Powell continues to chide India and Pakistan about dire consequences if either nation conducts new nuclear tests. "The Nuclear Security Agency's site readiness effort will unfortunately send exactly the wrong message to other would-be testers and test ban treaty hold-out states, including India, Pakistan and China," says Daryl Kimball of the Coalition to Reduce Nuclear Dangers. "It leaves the door open to a global chain reaction of nuclear testing, instability and confrontation in the future." However, the rising anxiety over the Bush administration's frank talk about resuming live testing of nuclear weapons may serve to distract attention from a more ominous venture: the development of a new class of nuclear weapons systems. Most of the action these days is in the innocuous sounding Stockpile Stewardship Program. The stated intent of the program was to maintain an "enduring" arsenal of nuclear weapons and components. But that mission has discreetly changed. Now the Pentagon and the DOE talk about the "evolving" nature of the stockpile. Evolving is a code word for improving. The nuclear labs are busy turning old nukes into new ones. During testimony before the House, Gordon groused that for the past decade the Pentagon had not been able to actively pursue new weapons designs. He said he wanted to "reinvigorate" planning for a new generation of "advanced nuclear warheads." "This is not a proposal to develop new weapons in the absence of requirements," Gordon told the committee in a gem of Pentagon doublespeak. "But I am now not exercising design capabilities, and because of that, I believe this capacity and capability is atrophying rapidly." Gordon wasn't being entirely truthful. The Pentagon and its weapons designers have been busy quietly crafting a variety of new weapons over the past decade. In 1997, they unveiled and deployed the B61-11, described as a mere modification of the old B61-7 gravity bomb. In reality, it was the prototype for the "low-yield" bunker blasting nuke that the weaponeers see as the future of the U.S. arsenal. The testing issue may be a kind of political bait-and-switch designed to garner more money for the Stockpile Stewardship Program. The gambit goes likes this: If you won't let us test the weapons, you've got to appropriate more money. Lots more. "The nuclear testing issue is a kind of red herring," says Greg Mello, director of the Los Alamos Study Group. "All discussion of possible 'nuclear testing' as the problem distracts attention from the real work of the complex, which does not need nuclear testing for 80 to 90 percent of its work. It is a form of blackmail." Instead of pursuing disarmament, the big prize for the weapons labs has been the lavishly funded Stockpile Life Extension Program, an array of projects designed to stretch out the operational life of existing weapons for at least another 30 years. Currently, four major nuclear weapons are undergoing major upgrading under SLEP: the B61, known as a "dial-a-yield" bomb with a yield of 10 to 500 megatons; W76, the warhead for the Minuteman III ICBM with an explosive power of 170 kilotons; the W80, a warhead for cruise missiles; and the W87, a warhead for the Peacekeeper ICBM. The Pentagon wants another 11 systems modified. These developments subvert the Pentagon's own official policy, signed by President Clinton in 1994, calling for "no new nuclear weapons production." The weaponeers at the Pentagon and the DOE are very touchy about the way they talk about these new bombs, being careful to speak in euphemisms like "reliability" and "safety" and "stewardship" of the "stockpile." "Energy Department managers have been sensitive to the hypocrisy in this program," Mello says. "The DOE honchos have even suggested that, given the political environment, the use of the word 'warhead' may not be acceptable." There's a reason that the Pentagon and the labs have fixated on the idea of producing a new line of low-yield nukes: They can be redesigned and deployed without a new round of underground tests. And that may be a big part of the bait-and-switch approach, with the Pentagon arguing that since they were prohibited from testing new weapons, they were forced to retool old ones into the new mini-nukes favored by the Bushies--nukes that are geared not for deterrence, but for use against recalcitrant regimes. But just because there's a push to build mini-nukes doesn't mean that the hawks have forgotten the big ones. According to the Bush squad, Russia still remains a threat and a justification for maintaining a robust strategic arsenal of bombs capable of leveling large cities. In this spirit, the Navy is teaming up with the Los Alamos and Sandia labs on a project called the Submarine Warhead Protection Plan. The labs and the Pentagon are desperate to protect their bomb-making mission, and they've done a good job of keeping the new schemes funded, including upgrades of several of the nuclear packages for Trident submarines. Los Alamos is also working on the development of new systems that will allow older "air-burst" weapons to be converted into bombs that explode close to the ground, thus becoming what Rear Adm. George P. Nanos delicately refers to as "hard-target killers." Beyond these pursuits, a host of other weapons design programs are up and running coast-to-coast, including: the insanely expensive National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore; plutonium pit factories; pulsed power plants; dynamic radiography facilities; tritium production plants; magnetized-target fusion research; an advanced facility designed to generate 3-D movies of imploding nuclear pits. These are the multibillion-dollar research toys of the modern weapons designer. In the end, the nuclear game always comes down to one overriding obsession: money. For the past 50 years, the nuclear programs of the Pentagon and allied agencies have been among the most extravagantly funded and sacrosanct items in the federal budget. During the height of the Cold War, annual federal spending on nuclear weapons programs averaged about $4 billion in today's money. The fiscal year 2002 budget proposed by Bush earmarks $5.3 billion for DOE nuclear programs, a figure that will almost certainly be generously boosted by Congress. Indeed, New Mexico Sen. Pete Dominici, the Republican guardian of the Los Alamos and Sandia labs, vowed in July to hold the entire federal appropriations bill hostage unless spending on military programs, including nuclear weapons research, was substantially hiked. In the political economy of nuclear weapons, enough is never enough.

Endless expansion is the relentless logic of a monopoly protected

by secrecy. "The nuclear weaponeers want it all," says Marylia Kelley,

director of Tri-County Cares, a Livermore watchdog group. "This

remains true regardless of who is president."

|