|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|||

|

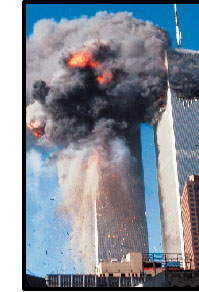

New York City is in a state of shock, mourning--and paranoia. Ordinary citizens are calling the police to report anything they think is suspicious, from a parcel to a person. Folks in the streets are sad and zombie-like. They stop and stare at the place where the vanished Twin Towers of the World Trade Center once rose above the skyline. Now all one sees are clouds of smoke. The victims of large-scale terrorist attacks are always, for the most part, ordinary working people. That's true of those New Yorkers trapped in the WTC's collapse--they'll turn out to be secretaries, clerks, service personnel, salespeople, civil servants, middle-class managers. As one bleeding, soot-covered survivor told a reporter, "We are all just people trying to make a living." And then there is the staggering loss of life among the courageous rescuers--some 300 firemen missing and presumed dead, as well as at least 50 cops and apparently some of the contingent of volunteer rescuers from Local 40 of the Iron Workers Union. Innocents all. September 11 began here as an inordinately quiet Primary Day. Despite many close

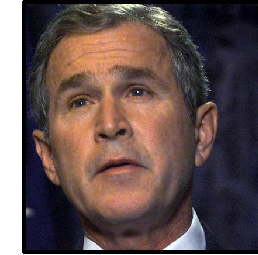

As these words are written just 24 hours after the hideous attacks on the Twin Towers, September 11 has already been baptized--in the newest media cliché--The Day America Lost Its Innocence. America is still, in many ways, an isolationist country, navel-gazing and turned inward, its people woefully ignorant of what goes on outside its borders. Foreign affairs, except in times of crisis, always rank at the bottom of Americans' concerns, and most--even in these days of the Internet--have only the most inchoate and cartoon-like notion of peoples and cultures beyond the two oceans that, until now, have sheltered us. "Globalization" as a process has been the sophisticated preoccupation primarily of the corporate elites and the governing classes they own or rent; but for the great majority, "globalization" has been only a dimly understood catchword, its role in maintaining the world in wage-slavery and poverty ignored. And the reality of U.S. foreign policy's impact on other peoples seldom penetrates our collective consciousness. Fortress America's complacency has now been shattered. In the first day's wall-to-wall TV coverage of the attacks, beyond the tragic body count, two things emerged as the most discombobulating for many: the audacious way in which our own airliners were turned into weapons against us and the effrontery of the attack on the Pentagon, that votive temple of American might. In our entertainment society, the phrase most often heard from the lips of ordinary folks was that the attacks were "like a movie." (The most often cited: Independence Day--but one worries that it could become The Siege.) We're different from the rest of the world; it has been a century and a half since this kind of violence was felt here at home--and most people are ill-equipped to comprehend its origins. All this explains why the inevitable result of Black Tuesday will be to drive this increasingly conservative country--already living through what historian Blanche Wiesen Cook has labeled "the meanest moment" in the life of this republic--even further to the right. TV coverage is whipping up a nationalist, revanchist frenzy: An overnight CNN/Gallup poll showed that 86 percent of those surveyed considered the attacks "an act of war"--the same language we are told President Bush used to his cabinet when he finally got back to the White House. ("IT'S WAR!" screamed the next-day headline in the Daily News.) In its usual incautious rush to judgment, television and its often ill-informed chatterers have already identified the culprits: Muslims and Arabs in general, Osama bin Laden in particular. In the first 24 hours, we were told that bin Laden could have organized the attacks through Islamic fundamentalists recruited from Algeria and Morocco. But the blithering heads never put this into context: There was no mention of how the United States has supported the dictatorial military kleptocracy that rules Algeria, which has killed and imprisoned thousands of its own people and has encouraged fundamentalist terrorism to distract from its own corrupt economic mismanagement. (No mention either of the joint Algerian-American military maneuvers that have helped inflame popular sentiment in the Maghreb against Washington.) Neither were viewers told of the long, despotic history of Morocco's monarchy--a major U.S. client regime--where, after a brief period of cosmetic democracy following the inauguration of the new, young King Mohammed VI, press censorship has been restored, newspapers critical of the royal police state suspended, and knocks on the door have resumed apace. In Afghanistan, the mujahedin we trained and supplied with weapons and money have morphed into the Taliban, bin Laden's somewhat reluctant hosts. (The Afghani leadership fears that if they give him up, they could be overthrown by their own supporters.) Coupled with the oh-so-often repeated clip of Palestinians on the West Bank celebrating the attacks--the schadenfreude of the have-nots against the haves--these and many other omissions have helped to fan the flames of hate across the country. Racial profiling of Arabs has been commonplace, from police in the nation's capital to state troopers in New Jersey (already infamous for their frequent pullovers of blacks), who reportedly arrested five Arab-looking men driving an explosives-filled van headed to blow up the George Washington Bridge. (This widely broadcast "news" proved false: There were no explosives in the van.) CNN repeatedly stubbed its foot on the truth throughout the first day, as when Judy Woodruff reported that the United States had started bombing Kabul (it turned out that the small-scale rocket attack was the work of the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance). Woodruff verged close to on-air hysteria--when reporting a rumor that the hijacked plane which crashed in Pennsylvania had been headed to attack Camp David, she blubbered that "this is the sort of report that makes you re-evaluate everything." Meanwhile, death threats against Muslim community institutions poured in. Shots were fired at a mosque and its school in Texas, and a mosque was firebombed in Michigan. The bashing of American Muslims, widespread after Islamic fundamentalists were initially (and erroneously) blamed for the Oklahoma City bombing, has already begun. Yet the parade of Bush administration leaders who showed up before the cameras throughout the first day uttered not a single appeal for calm and abstention from guilt by ethnicity. Particularly notable in his silence on this issue was Attorney General John Ashcroft, the constitutionally mandated guardian of our civil liberties (itself a disquieting thought--Ashcroft is a religious zealot nearly as mad as the Taliban). Not until 1 a.m. on Wednesday did I hear a network news anchor (Peter Jennings) make the common-sense observation that "entire communities should not be held responsible for the acts of a few individuals." And not surprisingly, verbal Arab-bashing was most in evidence on Rupert Murdoch's Fox Network. The president's nationally televised mini-address on Tuesday night--the most truncated

Shortly before Bush's speech, ABC's national security correspondent John McWethy--nicknamed "Colonel" by his colleagues for his muscular military affinities--was reporting, "They're ready to go to war. It's an atmosphere of war here at the Pentagon," whose collapsed section was still burning from the attack. The next day, the bloodlust for revenge had begun to spew from the mouths of senior politicians. The GOP's Arlen Specter and the Democrat Robert Torricelli both called for a Declaration of War by Congress. But against whom? Fill in the blank. The coming weeks are fraught with many perils. With Bush needing to prove himself a strong leader in combat and thus ensure his re-election, there is the probability of precipitous military action. (Former National Security Council staffer Gary Sick, now head of Columbia University's Middle East Institute, and Milt Bearden, the CIA's former man in Afghanistan, both have warned that the attacks appear to have been beyond bin Laden's capacities. And, as Sick pointed out, "intelligence is only as useful as those who evaluate it.") Bush needs to impose a body count on somebody to show what he's made of, and it seems to matter little whether those against whom we will inevitably riposte are actually the people who carried out the attacks. That's the implication of the overnight Washington Post poll showing that 84 percent of Americans want military action against any nation that "harbors or shelters" the terrorists (terms susceptible of an unsettlingly fluid definition). Bush's Oval Office speech claimed the attacks were visited on America "because we're the brightest beacon for freedom and opportunity in the world." That, of course, was a lie. However appallingly misguided and criminal the attacks were, they were surely fueled by seething rage at a long list of depredations over many decades--the support of despots, oligarchs and sanguineous dictators not only during the Cold War, but since; and the exploitation of the impoverished. A formal Declaration of War undoubtedly would be popular in this country, but it is fraught with domestic dangers: It would give the executive branch enormous latitude in speeding up the drive toward a garrison state on which Bush--with no visible dissent as yet from any Democrat--seems bent. Any attempt to block Bush's $18.5 billion raid on Social Security revenues to finance the Pentagon buildup? Fugeddaboutit--those numbers will only go up. In the wake of the attacks, Kent Conrad, the Senate Budget Committee's Democratic chairman, has already declared defense spending "our core priority." And voices in Congress are calling for giving intelligence agencies more domestic authority. (Bill Clinton's 1996 Anti-Terrorism Act contains many suspensions of civil liberties protections in terrorist investigations, but more will now be proposed.) Moreover, the Democrats' chances of holding on to their one-vote Senate majority or retaking the House, slim before the attacks, will be next to nil. (And whenever the New York mayoral primary is rescheduled, Freddy Ferrer might as well stay home. In the new wave of law-and-order sentiment, he'll be toast.) Here in Lower Manhattan, long lines of refrigerator trucks are pulling up outside the city's overburdened morgue to receive the thousands of corpses yet to be unearthed. The smoke and stench from the rubble of the Twin Towers is still seeping through the window of my apartment. CNN's Bill Schneider just announced a new poll showing three-quarters of Americans believe that "like Pearl Harbor and the JFK assassination, the events of the last 24 hours will change America forever." Not for the better, I greatly fear. For, as the poet said, when

the flag is unfurled, all reason is in the trumpet.

|