|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Vespertine LFO's 1991 album Frequencies, only the third release by the then young but now formidably influential U.K. label Warp Records, begins with a definition. "What is House?" asks a robotic voice, which then proceeds to answer its own question. "Technotronic, KLF or something you live in. To me, House is Phuture, Pierre, Fingers, Adonis, etc. The pioneers of the hypnotic groove, Brian Eno, Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, Depeche Mode and the Yellow Magic Orchestra." Ten years later, some of the names have faded or changed or been exchanged for others, but by and large the rules of electronic music remain the same. In the digital age of sequencers and samplers, influences are limitless, and electronic musicians can absorb as many of them as they desire and still spit out something relatively unique. If future historians ever want to know what sowed the seeds of rock music's slow demise, they need only look back to LFO's open-minded statement of purpose. Of course, rock music is not going to die any time soon, especially since some of the

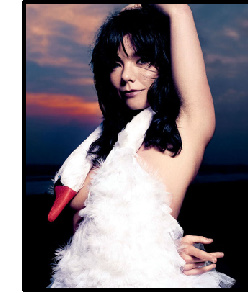

Despite electronic music's malleable stylistic trump card, the digital clubland revolution of the '90s never really happened, at least not as predicted. Despite fluke hits by the likes of Underworld, Daft Punk and Prodigy, or even the by now widespread name recognition of edgier artists like Orbital or Aphex Twin, electronic music failed to travel far beyond trend pieces and tight social circles to truly make a dent on popular music. Or did it? While programmers, beatmasters and synth tweakers were hardly catapulted to stardom, they have left a surprisingly extensive mark on what we listen to and even the way music is made. The vast majority of acts in the Top 40 now record their albums and singles on computers, using the kind of high-tech digital editing long enlisted by electronic artists. Further, the music itself often relies on elaborately programmed or sequenced synthesizers and drum machines. For example, the beats that producer Timbaland provides to Missy Elliott's songs get played on the radio and in clubs, but in many ways they're every bit as remarkable and complex as the aural fractals composed by underground favorites Autechre. With so many artists dabbling in or even fully embracing electronic music, you'd think more musicians would bridge the beatwise underground with the mainstream; that is to say, bridge the more abstract qualities of sound with the more accessible qualities of song. But so far there's only been a small handful of artists able to maintain their reputations as both pop stars and edgy experimental paragons. Of these, most fade in prominence as trends shift and fads wear out their welcome; consider artists like Laurie Anderson, David Byrne or even David Bowie, all of whom have dabbled in multimedia and specifically electronic music while ensconced in the mainstream, however tenuously. One exception to the rule, someone who keeps getting more popular (or at least more prominent) even as she grows stranger and more ambitious, is Björk Gudmundsdòttir. Like a lot of Icelandic citizens, the singular Björk has little use for her surname; phone books in Iceland are indeed alphabetized by first name alone. But to non-Scandinavian ears, Björk's name alone sounds fresh and new, like something a synthesizer might blurt out. Björk could be a slight variation on bleep, bloop or boing. After leaving her quirky band the Sugarcubes, Björk began her exploration of electronic music in earnest, initially via the tutelage of Soul II Soul producer Nellee Hooper but later via a bevy of notable producers, including Graham Massey of 808 State, Tricky and Howie B. In light of her quick evolution, Björk's first solo album, 1993's Debut, stands as her most straightforward (though still novel) effort, while subsequent albums sound increasingly foreign. The eclectic roster of producers behind 1995's Post helped Björk navigate techno and trip-hop, while the corresponding 1996 remix album Telegram reconfigured the music entirely as IDM (Intelligent Dance Music, which basically means dance music that you can't dance to or, alternatively, dance music you can listen to). Dismissed by some as an irritating eccentric, Björk has nonetheless never ceased pushing the limits of pop music. Björk's breakthrough arrived with 1997's Homogenic, not coincidentally produced by LFO's Mark Bell. The disc further blurred the distinction between song and soundscape, with Björk's dynamic and distinct voice just another instrument in the gorgeous yet challenging compositions. With strings meshing with abrasive and foreign beats, the disc was an inspiring hybrid, a mix of the familiar and the invented, like someone's imagination come to life. Fittingly, Björk capped off her greatest achievement with an astounding video, courtesy of director Chris Cunningham. "All Is Full Of Love" featured Björk as a lonely cyborg, creating and then making love to another cyborg cast in her image. The message worked on multiple levels. What Björk was doing musically was so special that she needed to create someone who fully understood it. Or Björk the human had been subsumed by Björk the machine, whose ability to reproduce mechanically did not replace the need for physical contact. But ultimately the song and video demonstrated that the chilly and strange sounds of Björk's electronic music did not preclude real emotion, however inhuman it might sound. Contrast this with Björk's 2000 follow-up, Dancer in the Dark. In the film, Björk is in many ways pure emotion, a non-actor directed by instinct as much as instruction. Her physical presence in the film coheres with the industrial clang of the corresponding music, sequenced sweeps and stomps that sound somewhat like Björk's most recent solo work, synthesized yet somehow still natural. How fitting that Björk should earn a number of awards and nominations both as an actor and composer; it's hard to know where Björk the person stops and her aura of creativity begins. Which brings us to Vespertine, Björk's most sedate and mysterious disc to date. Gone is Bell, replaced by a disparate cast of players and programmers including San Francisco's Matmos, New York harpist Zeena Parkins and an Inuit choir. Never has Björk sounded so much a part of the music, so much so that her lyrics seem almost secondary (not necessarily a bad thing, considering that one is written by pretentious provocateur Harmony Korine). Björk succeeds so well because she, unlike many of her predecessors, has been able to seamlessly blur the line between electronic music and her almost uncomfortably bare and intimate organic presence. In fact, Vespertine raises some interesting questions, mostly pertaining to presumptions commonly made about electronic music and ambient techno. Just when does a background drone of a soundscape become a song? Conversely, how does an artist transform a song into an ambient soundscape? In Björk's case these musical quandaries are handled with typical ingenuity, best exemplified through her live performances. Visibly contrasting the computer-based source of her songs with some of the most traditional instruments, Björk is bringing idiosyncratic chamber orchestras out on the road with her to support Vespertine. Her tour includes a troupe of string players, a choir, Parkins and her producers and current collaborators Matmos (whose own contributions to the blurring of the line between the electronic and organic include sampling bodily functions and slurping liposuction machines). These outings are her most ambitious to date, as Björk will

appear in such non-rock settings as opera houses, all sold out well

in advance. But she also plans to appear unannounced, in a handful

of small clubs where she can perform without amplification. Only

a performer as brave as Björk would dare to attempt to replicate

the atmospheric sounds of her music without the helpful crutch of

microphones and pre-programmed machines. Like the self-sustaining

cyborg of her fantasy, Björk doesn't even need to be plugged

in to express herself. She's like a force of nature, an extraterrestrial

voice connected to an all too terrestrial body that's constantly

trying to break free from the constraints of the corporeal. She

is literally the ghost in the machine, an artifact of humanity wrapped

up amidst all those wires and plugs, coursing through a maze of

circuitry like a jolt of electricity. Joshua Klein is a freelance writer who lives in Chicago. |