|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

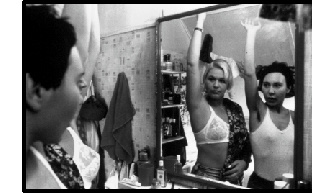

Together People are cracking up at the fuzz-headed but nonetheless strident commune-dwellers of Together, which is a good thing because I'm pretty sure it's a comedy. The laughs come from two places, both generally benign. First there's the sweet political nostalgia for a time--like this movie's sweater-vested Sweden of 1975--when certain people erupted into bearhugs at the news of Franco's death. (Even toddlers take part in the celebration, as good a moment as any for some quality jumping around.) Then there's the tension of alternative lifestyles in collision, presented here as not unfunny in itself, as when soft-spoken commune resident Göran (Gustaf Hammarsten) takes in his sister Elisabeth (Lisa Lindgren) and her two young children, in flight from an abusive husband. Strolling into the kitchen to meet their new housemates, they find themselves amidst a furious debate on gender expression involving, er, the bared expression of both genders. I don't believe there's much politics in Lukas Moodysson, who, only two features into his career, seems too exuberant a filmmaker to bear the inevitable comparisons being made to Ingmar Bergman, his famous countryman. That's fine, though. Moodysson's talents are more conservative, but done well and with conviction--an intuitive feel for the swelling pop song (Abba, with unexpected resonance) and an empathy for despairing teens that's refreshingly non-ironic. Show Me Love, his first film, was about two high-school girls easing uncertainly into a

But Moodysson hasn't the heart for cynicism; he lays out the casualties--vegetarianism, free love, radical activism--with a minimum of hand-wringing, replacing them with an overall acceptance that's unquestionably tamer but no less ambitious. "Solidarity is a word we have to strive for in some way," Göran says early on, and for all the yielding to pragmatism that follows, it's what he and his comrades end up with--a wised-up variety that survives its own revolution. The spiritual parent here is Alain Tanner's 1976 masterpiece, Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000, which shares with Together not only its historical context and warm utopian spirit--Jonah follows eight Swiss outsiders still flung on scruffy trajectories resulting from the political upheavals of 1968--but a similar desperation. As its title suggests, Jonah places its faith in a future generation that might make sense of things; now it finally is 25 years later, and Moodysson's children walk the same line. This push and pull is best captured in two awkward displays of parenting: In the first, Elisabeth's kids watch in shock as their estranged father, Rolf (Michael Nyqvist), makes a scene at a Chinese restaurant upon hearing they won't be getting Christmas presents at the commune (too rampant a display of materialism). Rolf eventually becomes a drunken menace, getting himself arrested and leaving the kids stranded on a chilly Stockholm street. So it's a strangely comforting sight when the hippies' trippily hand-painted VW bus lumbers up to the curb and responsibly spirits them home to bed. The spell is too good to last, as Elisabeth insists on fussing over the pillows beneath their slumbering heads, switching them from the usual blue-for-boys, pink-for-girls. Moodysson excels at this delicate staging of inappropriateness; his true theme begins to cohere out of the sullen stares of children forced to tap undeveloped reserves of patience as the adults test the limits of liberation. Elsewhere, the camera is zoom-happy, a redolent nod to '70s solipsism,

but also an amplification of the daily shockwaves rumbling the liberated

front: Göran can tell his girlfriend how happy he is for her

on the occasion of her first orgasm--with another man--but his brow

is troubled for most of Together. When many of these dissonances

fall away in a final scene of collective euphoria, a sloppy soccer

game in the falling snow, it's a moment of such sublime generosity

it feels like a gift.

|