Bohemian Rhapsody

By Sandy Zipp

Wierd Like Us:

My Bohemian America

By Ann Powers

Simon & Schuster

288 pages, $23

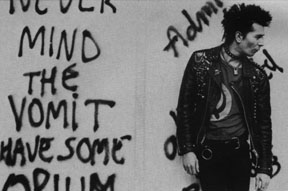

Bohemia," wrote Malcolm Cowley, "is always yesterday." His classic Exile's Return (1934) looks back to the "literary odyssey of the 1920s" for its nostalgic and bitter take on the fortunes of artistic dissent, but there is something historically constant about the sense of romantic dilettantism and utopian wishfulness that always shadows bohemian rejections of middle-class comfort. This is a fundamental paradox within so many supposedly avant-garde artistic moments--an old-fashioned aura deployed for forward thinking aims. Perhaps, as commentators on bohemia have often noticed, this is because bohemia is closely tied to the "bourgeoisie" it habitually disavows.

Bohemia requires the respectable, striving present as a foil for its imagined past and projected future. All the familiar artistic tropes that have energized various bohemian moments down through the years--sacred ideograms and mystic visions, idyllic childhood and vicarious poverty, Orientalist fantasies and picturesque primitivisms, erotic excess and flirtation with madness--are staged as retreats from the inexorable spread of what Cowley's generation called "Babbitry." They are ripostes against the businessman's culture of the mass palliative, the secure cul-de-sac laid out by the Saturday Evening Post, Pat Boone, the Rockefeller Foundation or Time-Life that always, by definition, threatens to corrupt bohemia's seditious gestures of nonconformity.

|

|

|

Mainstream

culture co-opts bohemia's countercultural |

It is no mistake, then, that most chroniclers of bohemia--whether leering tourists or jaded memoirists--have been mired in the same fascination with invented pasts and conjured foreign lands. The story of bohemia is almost always a look back to a world now gone, just subsumed by the tide of conformity it was both born from and scurried to reject. In one sense Ann Powers' new book, Weird Like Us: My Bohemian America, is little different from its predecessors. Her hybrid version of memoir and social reportage is a look back on American underground culture of the '80s and '90s, its various flirtations with mainstream influence, and its eventual emergence as one of the prime spectacles at the heart of information-era capitalism's Wall Street-fueled boom.

With a note of regret that will be familiar for many of her cohort in the underground of the '80s, Powers recounts her own loss of bohemian innocence as a parallel to the culture-wide cash-in that corporate America found in the "alternative" aesthetic. Her final chapter, called "Selling Out," tells how she moved from San Francisco, where "girls in thrift store dresses" wander the sun-dappled streets, to New York and a job with Moloch's house propaganda organ, the New York Times, reviewing music industry product for jaded straphangers and starry-eyed bridge and tunnel drones. But while Powers' book has its share of lament, often of the hackneyed variety, she ultimately veers away from loss toward celebration. For her, bohemia survives in the ruins of its former splendor. Sifting through the historical fallout of that old '60s imperative to break down the walls between the personal and the political becomes a search for residues of true cultural invention and considered ways of living.

![]()

|

In These Times ©

2000

Vol. 24, No. 7 |

|