|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

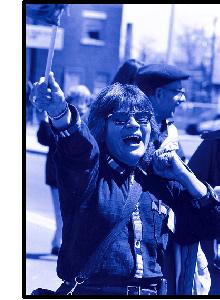

NAFTA's advocates promised that free trade would bring a new era of respect for workers rights in the North America. Especially south of the border, they said, the treaty's labor side agreement would ensure that workers could vote freely for the unions of their choice in clean elections by secret ballot. But a recent election at the huge Duro bag plant in Rio Bravo, just across the border from Texas, could become a symbol of how those promises have been broken. And with more promises on the horizon--as the Bush administration pushes for fast-track authority to extend the treaty across the whole Western Hemisphere--Duro may become the poster child for NAFTA's failure to protect workers rights. On March 2, voting began inside the Duro factory, where workers labor around the clock cutting and gluing fancy paper bags for the U.S. gift market. On the ballot were two unions--the Union of Duro Bag Workers, an independent union organized by rank-and-file workers, and the Revolutionary Confederation of Workers and Peasants (CROC), a company union affiliated with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), Mexico's former ruling party. The stage was set the day before, when observers outside the plant watched automatic

The next morning, workers from the day shift were escorted to the voting area by CROC organizers, who handed them slips of paper printed with the union's local number. At the voting table, representatives of Mexico's national labor board asked workers to declare their choices out loud. Company foremen and government-affiliated union representatives took notes. In the end, only 502 people voted out of a work force of more than 1,400. Only four of them openly declared their support for the independent union. "The Duro election is clearly a tragic defeat for the workers," says Robin Alexander, director of international relations for the U.S.-based United Electrical Workers, which supported the independent union. "I hope the violations here will serve as a wake-up call." Duro's vice-president of manufacturing, Bill Forstrom, says wages at Rio Bravo start at $6 a day. "We're in Mexico to take advantage of inexpensive labor," Forstrom admits. According to Eliud Almaguer, a fired rank-and-file leader from the Rio Bravo plant, many people have lost fingers in machinery because of fast production and little protection. Such poor wages and working conditions have led to a long history of agitation at the plant. Ludlow, Kentucky-based Duro Bag Manufacturing Corporation also operates seven U.S. plants. For years, Duro has paid local leaders of the Paper, Cardboard and Wood Industry Union to guarantee labor peace at the plant. The union is part of the Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM), which has been a pillar of support for the country's ruling bureaucracy since the '40s. Two years ago, workers in the Duro plant decided to challenge that contract and elect reform-minded union leaders, including Almaguer. That led to Almaguer's firing in October 1999 and a work stoppage a year ago, when 150 more workers were terminated. The CTM then signed a new agreement with Duro, with none of the higher wages and increased safety demands the workers were seeking. The Rio Bravo plant began organizing an independent union in response. When the election finally took place this March, none of the fired workers were allowed into the plant to vote. The CTM, which had grown increasingly unpopular, withdrew from the process the morning of the election and was replaced by the CROC. Many workers didn't even know the name of the union they were told to vote for. During the past year, however, Duro workers have been supported from the north by the San Antonio-based Coalition for Justice in the Maquiladoras, a coalition of North American unions, churches and community organizations. Help also came from Mexico's new independent labor federation, the National Union of Workers (UNT), based in Mexico City. Last summer they pressured the governor of Tamaulipas state, where the plant is located, into granting the independent union legal status. The company's legal battle was handled by attorneys from the Mexican employers' association, COPARMEX, the equivalent of the U.S. National Association of Manufacturers. This has been very beneficial to Duro--Mexico's new Labor Secretary Carlos Abascal was formerly the chief of COPARMEX. When Duro's independent union presented its petition for election to Abascal, they requested it be held on neutral ground with a secret ballot. Abascal denied the request, and the federal labor board, under his control, went on to administer the balloting in Rio Bravo. Abascal's orders violated an agreement negotiated between his predecessor, Mariano Palacios Alcocer, and former U.S. Labor Secretary Alexis Herman. That agreement grew out of two celebrated cases filed under the NAFTA labor side agreement--at the Han Young plant in Tijuana, and the ITAPSA plant in Mexico City. Abascal's decision to ignore it is one more dent in NAFTA's already-tattered credibility. Since NAFTA went into effect in January 1994, more than 20 complaints have been filed under the labor side agreement. Almost all have charged that Mexico does not enforce laws guaranteeing workers the right to form unions of their choice, and to strike effectively when they do. But nothing has been done to rehire a single fired worker, nor has a single independent union been able to negotiate a contract. In Tijuana last June, independent unionists from the Han Young factory were even beaten and expelled from a public meeting about workers rights called by the Mexican government (see "Tijuana Troubles," August 21, 2000). U.S. officials present at the time made no public protest over the violence and expulsions. But they did boast about one outcome of the Han Young case: According to Lewis Karesh, a former deputy U.S. labor secretary who headed the office which hears NAFTA complaints, the Mexican government promised that workers would be able to choose union representation by secret ballot. "The Duro election strips away any idea that the NAFTA process can protect workers rights," says Martha Ojeda, director of the Coalition for Justice in the Maquiladoras. "The side agreement is bankrupt." Events at Duro throw doubt on President Vicente Fox's promise that he intends to be more democratic than his predecessors. Labor activists on the border, in fact, see the denial of a secret ballot as consistent with the pro-business policies of his National Action Party (PAN). In states like Baja California, where the PAN has been in power for a decade, the party has fought efforts to organize independent unions. Strikes like the one at Han Young have been broken and court orders ignored. The Duro vote also calls into question claims that treaties like

NAFTA provide any mechanism for protecting workers rights. "Duro

shows that for both the U.S. and Mexican governments, when the chips

are down, their interest is in promoting investment," Alexander

says. "Free trade clearly outweighs any commitments they make about

labor rights. Institutions like NAFTA and the WTO will never operate

in workers' interests. What's needed is an independent institution

on an international level."

|