The DCCC's Long, Ugly History of Sabotaging Progressives

The latest attacks on left challengers are no fluke: For decades the House Democratic fundraising body has put corporate, big-money interests first.

Above: Laura Moser, a progressive House candidate in Texas, was subject to a smear campaign from the DCCC, which posted a memo in February labeling her “a Washington insider.” (Photo by Michael Robinson Chavez / The Washington Post via Getty Images)

April 5 | May Issue

In February, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) attempted to undermine Democratic primary candidate Laura Moser out of fear she’s too far left. The Houston journalist and activist is running in Texas’s 7th District on a platform of single payer, gun control and reproductive rights. In a move typically reserved for Republican opponents, the DCCC—whose mission is to fundraise for Democratic House candidates—posted opposition research it had conducted on Moser. Citing her recent move to Texas from Washington, D.C., and her campaign’s payments to her husband’s D.C. research firm, the memo portrayed her as corrupt and a carpetbagger. Despite these attacks, Moser came in second in the primary, moving on to a May 22 runoff. This could well be the year the Democrats take control of the House for the first time since 2010. Of the 90 seats the party is targeting for November, just 24 need to turn blue, a prospect made all the more exciting by the Bernie Sanders-inspired deluge of progressive candidates around the country. But the DCCC is emerging as that movement’s counterweight, if not downright enemy.

From the May 2018 issue

Turning the house purple

The DCCC, chaired by Rep. Ben Ray Lujan (D-N.M.), has teamed up with the House’s centrist Blue Dog caucus to recruit candidates for the 2018 elections, attempting to replicate the 2006 strategy of then-DCCC chair Rahm Emanuel. Democrats did win back the House in 2006 (arguably due as much to George W. Bush’s historic unpopularity as to Emanuel), but the influx of conservative Democrats contributed to a watering down of the Affordable Care Act and Wall Street reform, a shift to austerity, and, eventually, legislative stalemate.

That doesn’t seem to bother the DCCC.

The Committee’s recruits are heavily weighted toward military veterans and former national security officials. Elissa Slotkin, a DCCC-backed candidate in Michigan’s 8th District, worked for the CIA in Iraq under John Negroponte before moving to George W. Bush’s National Security Council and then Barack Obama’s State and Defense Departments. Slotkin was an architect of the failed “surge” strategy in Iraq and continues to claim it as a success. As recently as 2014, she praised Negroponte—whose claim to fame is covering up the atrocities committed by Reagan-supported right-wing forces in Central America.

The DCCC’s candidates also skew toward the well-heeled and well-connected. An heir to a liquor fortune, a millionaire philanthropist, a furniture company heir and former State Department official, the former executive of a shoe company once accused of labor abuses: All appear on the DCCC’s 2018 roster. Angie Craig, running in Minnesota’s 2nd District, was an executive of a powerful medical technology company and spent her time there funneling money to mostly Republicans.

In Nebraska’s 2nd District, the DCCC lent a hand to Brad Ashford—a former Republican who favors abortion restrictions—at the expense of his more progressive primary challenger Kara Eastman, who supports reproductive rights, Medicare for All and other progressive policies. Over in Virginia’s 2nd, the DCCC swung in early behind businesswoman Elaine Luria, a military veteran who twice voted for her Republican opponent, over Karen Mallard, a union member who supports a $15 minimum wage and universal healthcare.

DCCC officials and alumni have also reportedly stepped in to nudge progressive candidates out of several House races. In Colorado’s 6th, a Democratic-leaning swing district where Republican Rep. Mike Coffman is considered vulnerable, party officials are reportedly trying to clear the field for DCCC-trained former Army Ranger Jason Crow. Levi Tillemann, a progressive candidate whose campaign is managed by a Sanders 2016 alum, says he was asked in January by Minority Whip Steny Hoyer—a former DCCC official and major fundraiser—to exit the race because Democratic leaders had decided “very early on” to back Crow.

In Pennsylvania’s 7th District, the DCCC pressured out a progressive because they felt their pick would be a better fundraiser. In California’s 39th, it was to make way for a lottery-winning lifelong Republican who switched parties because he believes the Democrats are closer than the GOP to Reagan-era Republicanism.

The DCCC appears reluctant to support progressives even when they present the only opportunity to flip a red seat. Last year, the Committee largely stayed away from the special election for Montana’s at-large district, spending a mere $340,000 on populist Rob Quist’s surging campaign, compared to the millions it poured into centrist John Ossoff’s bid for Georgia’s 6th district.

In the April 2017 special election for Kansas’ ultraconservative 4th District after Mike Pompeo was tapped as Trump’s CIA director, progressive James Thompson was frustrated that the DCCC put its resources to work only at the last minute. Thompson still came within seven points of flipping the district. Yet Thompson, who’s running again this year, isn’t featured on the DCCC’s list of “Red to Blue” candidates to support—those running in Republican-held districts ripe to turn.

For all this electioneering, the DCCC’s hit rate hasn’t been stellar. In 2016, its preferred candidates lost 23 districts that Hillary Clinton won.

A long tradition

What explains the DCCC’s allergy to progressives? Part of the story lies in its history.

The 152-year-old organization has always been devoted to getting more Democrats elected, but its secondary mission has increasingly become the courting of wealth. As campaigns became more expensive with the advent of television, the DCCC began to alter its fundraising strategy from a single annual dinner to a year-round program with a full-time staff. In 1972, the Committee was used as a vehicle to funnel money to moderate Democrats from donors “opposing or cool” to George McGovern, as the Washington Post put it, but who didn’t want the donations to appear on their financial reports. These included BankPac (the American Bankers Association’s PAC) and the Mortgage Bankers PAC, among others.

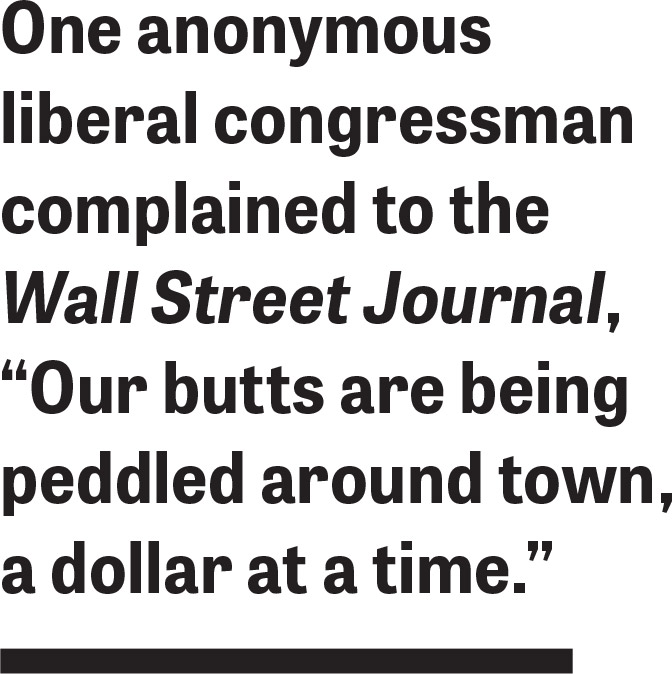

Above: Rep. Tony Coelho (D-Calif.) embraces Rep. Martin Olav Sabo (D-Minn.) in 1989. As DCCC chair from 1981-1989, Coelho greased the way for lobbyists to access Democrats—for a price. (Photo by Laura Patterson/CQ Roll Call via Getty Images)

The DCCC’s first major scandal came not long after. Chair Ohio Rep. Wayne Hays was tasked in 1973 with leading campaign finance reform in the House, a “whopping conflict of interest,” as the Philadelphia Inquirer noted at the time. Hays was known to “donate” funds from the DCCC and elsewhere to Democratic friends, even when they faced no GOP challenger. As head of the House Administration Committee, he dragged his feet on campaign finance reform and fought off attempts to unseat him by, among other things, reminding freshmen Democrats about the campaign funds he controlled. Hays ultimately resigned in 1976 after a clerk alleged she had been hired to provide him sexual services on the taxpayers’ dime.

The chair of the DCCC from 1981 to 1989 was Rep. Tony Coelho (D-Calif.), a fiscal conservative who endorsed the balanced budget constitutional amendment. Coelho raised mountains of cash by opening up the DCCC’s fundraising to defense contractors, oil producers, venture capitalists and other businesspeople that, as he put it, “the party kicked away in the 1970s.” Coelho resigned under an ethical cloud, but later served as an unpaid advisor to the Clinton administration, where he refused to publicly reveal his clients at his day job as an investment banker.

Under Coelho, hundreds of lobbyists and lawyers started attending the DCCC’s annual fundraising dinners. A brochure for Coelho’s “Speaker’s Club” promised members that, by donating thousands of dollars, they would be “assured courteous and direct access to” and “relaxed intimacy” with Democratic leaders and members of Congress. One anonymous liberal congressman complained to the Wall Street Journal, “Our butts are being peddled around town, a dollar at a time.”

In 1981, as representatives of the commodities industry embarked on a massive lobbying effort to prevent a clampdown on a tax avoidance scheme, Coelho told Democrats on the Ways and Means Committee that two of the industry reps were “friends of the Democratic Party, so don’t be too rough on them.”

Coelho eventually departed Congress, but the intertwining of Democratic politics and money interests never did. In 1991, Steven Soren, an Iowa Democrat, wrote in the Washington Post of his “appalling” experience as a congressional candidate, which, for him, embodied a worrying and “dramatic shift from participatory democracy to a highly centralized and manipulative system.”

At DCCC workshops in 1990, he explained, wide-eyed candidates-to-be were imparted advice like: “Money drives this town” (DCCC staff member Marty Stone), “You have to sell yourself in Washington first” (consultant Tom King) and “Raising campaign money from Washington PACs is much easier than from individuals because it’s a business relationship” (Nebraska Rep. Peter Hoagland). At one of the workshops, Rep. Beryl Anthony (D-Ark.), a former head of the DCCC, told corporate PAC representatives that they would be able to pick winners in the room that would “make your board of directors proud.”

Big money

Twenty-eight years later, little has changed. While the DCCC has seen a “Trump bump” in the form of a record surge of small-dollar donations for the 2018 election cycle, its model is still stuck in big-donor mode. As The Intercept reported, the DCCC routinely requires its candidates to be able to raise at least $250,000 from the contacts in their phones, thereby leaning toward well-connected, wealthier candidates who tend to sit on the party’s right.

The DCCC’s funding structure incentivizes candidates who can cough up—or pull in—big sums. Much of the DCCC’s purse is filled by the dues Democratic House members pay every election cycle. A spreadsheet leaked to Buzzfeed in 2014 detailed some of these dues: $450,000 to $800,000 for House leadership and $200,000 to $500,000 for committee members and chief deputy whips. As a 2017 report from Issue One, an ethics watchdog group, put it, these dues act as “committee taxes,” forcing lawmakers to fundraise if they want to sit on or chair powerful committees, and making fundraising skills—not experience or knowledge—the most important qualification.

“Because of this pressure for fundraising, members have to spend a whole lot of time dialing for dollars rather than legislating,” says Eric Heberlig, professor of political science at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

These dues, which the DCCC’s Senate counterpart doesn’t levy, were at first limited to top brass. Heberlig says this changed with the GOP’s first-in-40-years takeover of the House in 1994. “The party realized that if it got its incumbent members to chip in, they could take money from donors who had business before Congress and shift it to competitive districts.”

After legal limits were placed on “soft money” in 2002, the DCCC ratcheted dues up substantially. When Minnesota Rep. Collin Peterson fell behind on his dues in 2004, Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and other Democrats warned him that he would be passed over for a ranking position on the House Agriculture Committee. He began raising increasing amounts from business PACs and large donors.

There’s also the influence of lobbyists. In 2017, the DCCC’s top five lobbying bundlers alone brought in more than $1.3 million. One was Nancy Zirkin of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a progressive group. The other four—Steven Elmendorf, Vincent Roberti, David Thomas and Tony Podesta—count or have counted among their clients a dizzying line-up of corporate giants, including just about every major pharmaceutical company you can think of: Pfizer, Amgen, Sigma, Novartis.

Three of these lobbyists—Podesta, Thomas and Elmendorf—have previously represented the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, an industry lobbying group that fiercely fights attempts to lower drug prices.

Such fundraising comes with access. A document leaked by one of the suspected Russian hackers in 2016 showed lobbyists for Goldman Sachs and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association—whose PACs had donated to the DCCC—complaining to DCCC chair Ben Ray Luján about “messaging demonizing Wall Street” and the influence of Elizabeth Warren. Luján reassured them that Warren didn’t speak for the party.

Perhaps the influence of Big Pharma donors helps explain why a DCCC-commissioned report leaked in February discouraged House members from campaigning on Medicare for All—the policy that most distinguishes progressive challengers from the DCCC’s centrist picks.

Money over power

Sanders has expressed disgust at the DCCC’s recent efforts to stomp out progressive challengers. He told The Hill in March, “That just continues the process of debasing the democratic system in this country and is why so many people are disgusted with politics.” He called the organization’s attacks on Moser in Texas “appalling” and “unacceptable.”

At a critical time for the Democratic Party to start winning, the establishment appears content to follow the same blueprint that left the party in electoral shambles. Then again, challenging the status quo and advancing a progressive agenda have never been the business of the DCCC, so long as the money keeps flowing.

is an editorial assistant at Jacobin magazine and a regular contributor to In These Times. He hails from Auckland, New Zealand.

Want to stay up to date with the latest election news? Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter: