Wall Street Isn’t the Answer to the Pension Crisis. Expanding Social Security Is.

The economic fate of workers shouldn't be tied to a stock market that rewards assaults on the working class.

January 22 | February 2018 Cover Story

State and local public pension funds across the country are in political and economic crisis. At stake is a comfortable and deserved retirement for millions who have spent their lives serving the public—teaching our children, picking up our garbage, running our libraries. The crisis could also profoundly affect the budgets of state and municipal governments, already weakened by decades of austerity.

The Right decries this parlous situation and demands savage cuts. The unions and their friends say there’s no problem—just reactionaries crying wolf to push an austerity agenda.

But despite the clear bad-faith agenda of the Right—at a recent conference of the Koch brothers’ political network, one speaker joked about their efforts to “bring down the [Alabama] pension system”—the pension problem is real.

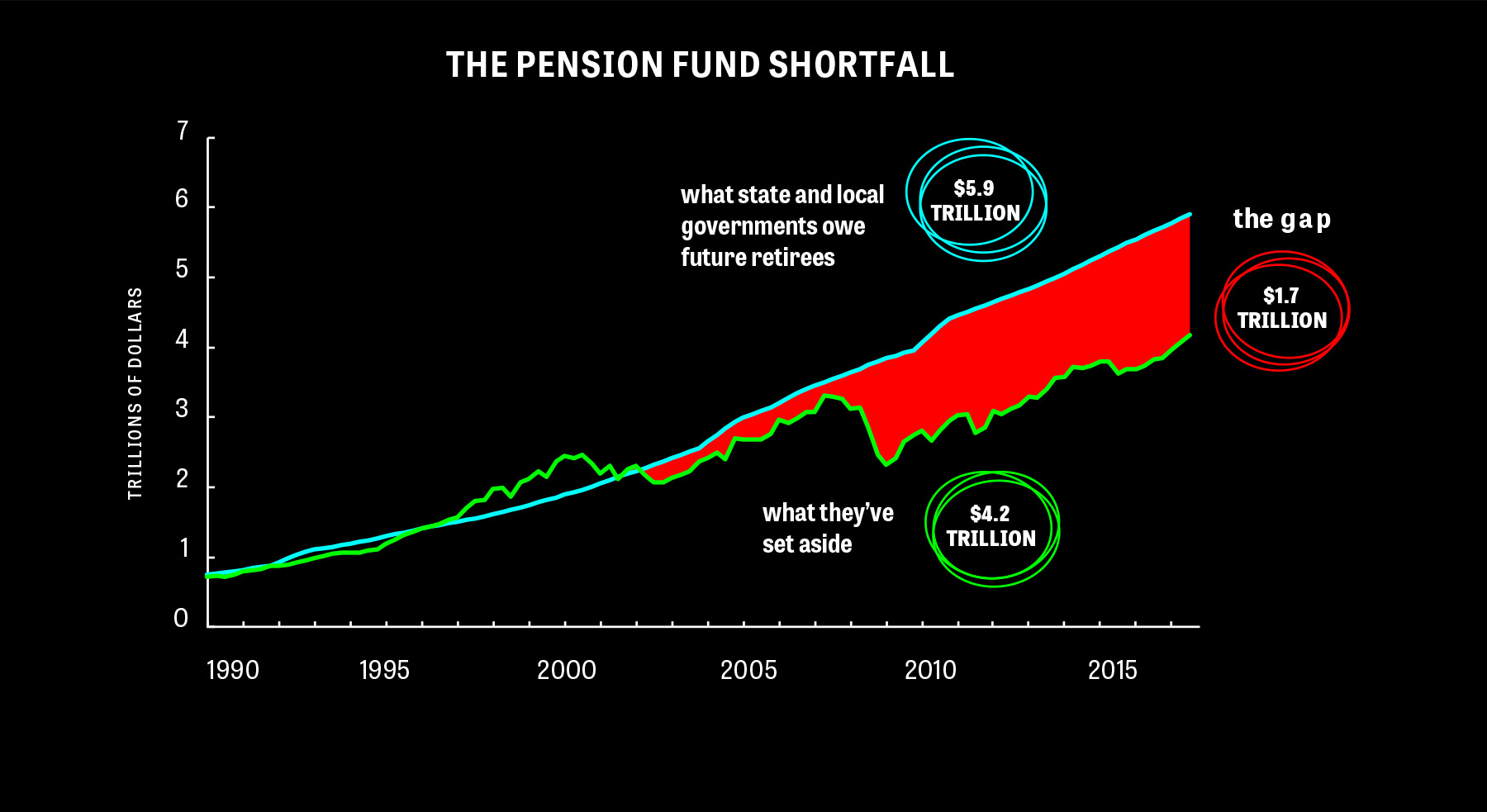

Governments have promised trillions of dollars to present and future retirees—$5.9 trillion (according to Federal Reserve statistics)—to be paid out sometime in the future. Unfortunately, they don’t have anywhere near that kind of money, either on hand or in the foreseeable future. Crisis-driven cuts have only made the situation worse. The Fed has calculated that, all told, the nation’s pension accounts are $1.7 trillion in the hole—and others put the shortfall at closer to $4 trillion.

It didn’t have to come to this. During the New Deal, unions advocated for an expansion of Social Security to fund pensions. What they got instead is the current pension fund system, one that is in thrall to both the vagaries of Wall Street and prevarications of politicians. Perhaps, with crisis looming, the time is nigh to consider scrapping the current system and going back to the idea of publicly provided pensions for all—a universal basic retirement income.

Currently, pension funds work similarly to individual retirement accounts. Participants set aside some current income to provide for the future, with interest, dividends and capital gains offering an assist. Governments, too, are supposed to pay in, but for years they have been stinting on contributions. Faced with an unpleasant choice between raising taxes or cutting services to meet a budgetary pinch—or, in some cases, to finance tax cuts—elected officials often decided to skimp on pension pay-ins. For politicians, it’s an easy can to kick down the road, as most won’t be in office when the pension crisis hits. To get the books to balance, public officials assume that markets will essentially boom forever, providing an effortless gusher of cash for retirees. The problem is that the markets may not cooperate, and now that the Baby Boomers are retiring in large numbers, long-deferred bills are coming due.

Worse, the pursuit of unrealistic returns has led union pension managers to invest heavily in hedge funds and private equity, sectors with a viciously anti-worker agenda. This practice forces workers to bet against fellow workers. Longtime labor organizer Stephen Lerner calls this dynamic the labor movement’s “assisted suicide.”

The grim math

Pension fund managers have to make several assumptions: how long people will work, how long they will live and how much the financial markets will return over the next few decades. Generally, they assume the future will be more or less like the past. That works for life expectancy, which does not change rapidly, and for retirement age, which follows historical patterns (the fantasy that boomers wouldn’t retire like earlier generations hasn’t panned out). But the stock market, everyone’s favorite source of effortless wealth generation, is a fickle friend.

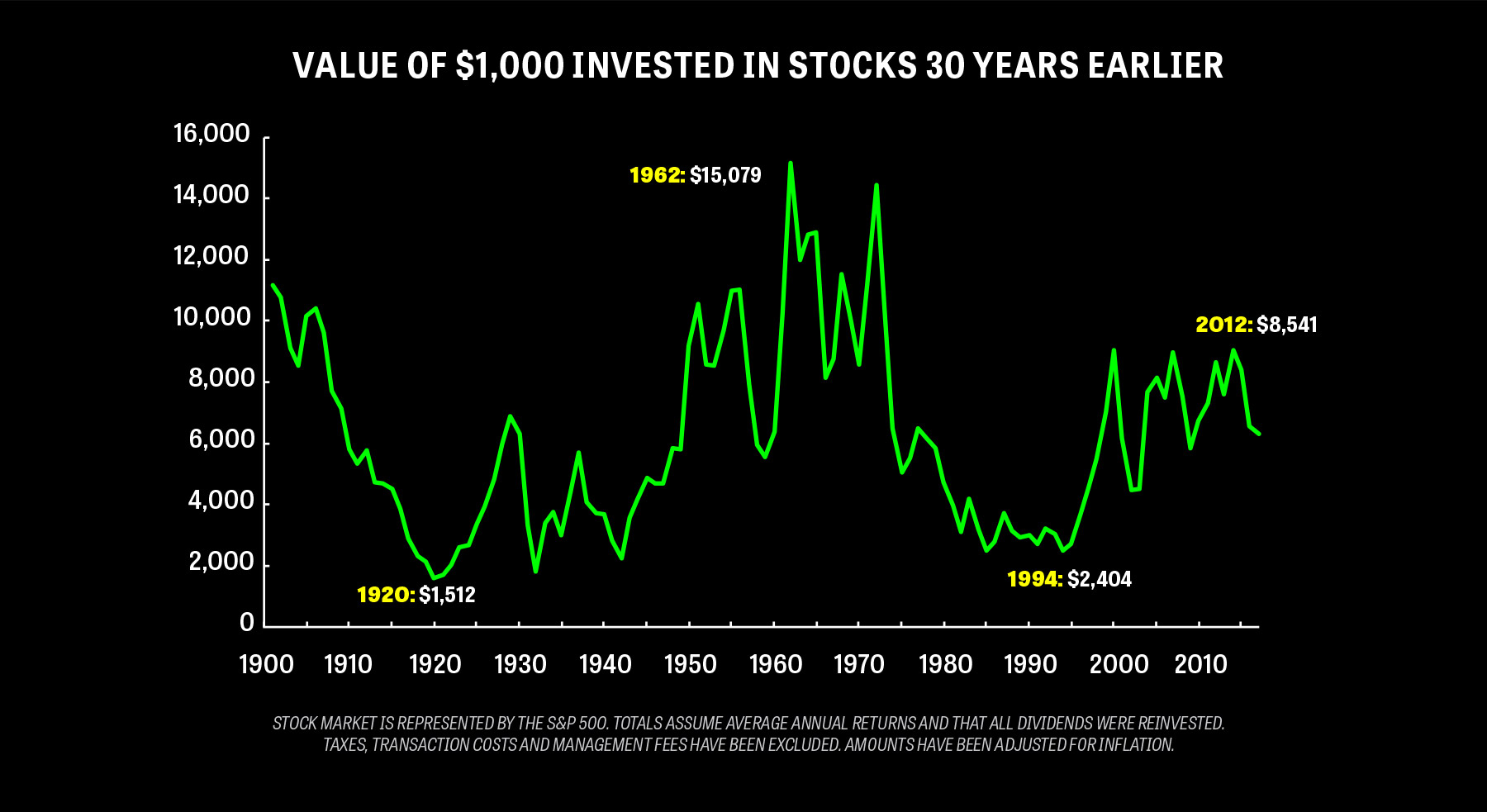

Yes, over the very long term, stocks return close to 7 percent a year after inflation. But stocks are also very volatile, and 7 percent is far from a guarantee. For example, money invested in 1982 would accrue annually by an average of 7.8 percent over 30 years, compared to only 4.2 percent for money invested in 1964. By the magic of compound interest, the 1982 investment yields almost quadruple the final balance of the 1964 investment (see graph above).

These hypothetical returns are just estimates, of course. You’d have a hard time matching them in the real world, given taxes, commissions and fees. The point is, assuming “average” returns is a very poor guide for someone depending on an investment. This is especially true now, with stock prices having quadrupled since their Great Recession low in March 2009, to some of the highest levels in history relative to underlying corporate profits. Historically, high stock valuations portend crummy future performance.

According to Joshua Rauh, a professor of finance at Stanford, state and local pension systems assume an average annual growth of 7.6 percent. He looked at 694 pension systems—systems that account for more than 97 percent of total state and local pension assets. Rauh also found that the average worker contributing to a pension fund was about 10 years from retirement. If you assume a 7.6 percent return, the nest egg you set aside today would double in those 10 years.

Unfortunately, as Rauh points out, 7.6 percent is far from the most prudent standard for pension accounting. Because Treasury bonds are the safest and most predictable investment available, pegging promises to their interest rates would be the surest way to estimate how much a fund needs to set aside to meet future obligations without a bailout. The 10-year Treasury bond rate is currently about 2.5 percent. At 2.5 percent, an investment will take almost 30 years to double. At that rate, current pension accounts are headed for a shortfall of nearly $4 trillion on the total U.S. pension obligation of $5.9 trillion.

One standard response from the Left might be to dismiss Rauh’s analysis because he is a fellow at the right-wing Hoover Institution, which published his paper. But his math is correct. You could argue that 2.5 percent is too pessimistic a baseline—after all, it could go up. Financial history, however, suggests the 7.6 percent assumption is recklessly optimistic. Yes, the Right wants to make the pension funding situation look dire, but union leaders avoid the consequences of this uncomfortable math either because they are reticent to face up to its implications for their members or because they have become apologists for the giddier assumptions. For example, union-friendly academic Gordon Lafer, in The One Percent Solution: How Corporations are Remaking America One State at a Time, credulously endorses the finance sector’s magical thinking, delighting in the opportunities presented by “volatile but higher-earning equity markets.” He summons a Wall Street investment advisor to offer supporting testimony, and sings the praises of “professional managers,” approvingly gushing that they “make better investment choices” than individual workers, basing their decisions on “long-term horizons.”

The problem isn’t just one of math, however. It’s also unclear how allying with financiers will advance the interests of working people.

Above: A thousand dollars invested in the market may be 15 times that down the road, or sometimes, pretty much the same amount.

Squeezing workers for interest

In search of higher returns, pension fund managers have taken to what are known in the trade as “alternative investments,” such as hedge funds and private equity.

Although distinctions can blur, hedge funds are aggressively managed—run by professionals intent on making boatloads of money quickly, which means they can also lose boatloads of money suddenly. They trade in what is known in economics as “hot money”—highly speculative, short-term capital investments that create massive market instability by moving money fast. That instability has greatly increased the precarity of the working class, fueling, for example, the housing bubble that led so many to lose their homes to foreclosure.

Private equity (PE) generally has a longer time horizon, with fund managers investing in a business for several years. Their aim is to increase a company’s profitability by increasing its “efficiency,” then sell their stake at a profit. In the interim, PE funds often take cash out of the business through dividends and fees. PE can be a very lucrative line of work, and managers enjoy special tax breaks on top of their big paychecks.

So-called efficiency is often code for “screwing workers.” An infamous example is what happened at Safeway stores in the 1980s. By mid-decade, the unionized supermarket chain was suffering increased competition from lower-cost nonunion stores. In 1986, the company went private in a leveraged buyout engineered by boutique investment house Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR). In a leveraged buyout, a small group of investors (in partnership with corporate management), borrows lots of money to buy out a business. That debt is often quite burdensome, which is part of the point: The urgency of the debt becomes a disciplinary force, driving management to achieve greater “efficiencies.” In the case of Safeway, that meant selling off divisions (mostly to nonunion operators), closing stores and squeezing labor. In all, 63,000 people lost their jobs. The human toll was detailed by Susan Faludi in a 1990 article for the Wall Street Journal: suicide, alcoholism, heart attacks, bankruptcy and broken lives. Displaced workers had a hard time finding new jobs, and those who did saw their pay cut by, on average, more than half. But KKR made off with $7.2 billion, after an initial investment of $129 million.

This isn’t an unfamiliar story for anyone who’s been following American capitalism for the last several decades. Less widely known is that KKR, the era’s leader in leveraged buyouts, got a lot of its financing from public pension funds. In its early days, KKR had trouble raising money for its adventures, such activities being seen as disreputable in the sleepy pre-Roaring Eighties culture of Wall Street. KKR’s efforts were greatly assisted when the Oregon state employee pension fund, no doubt dazzled by the potentially glorious returns, kicked in some cash. With a respectable institutional investor like that in its stable, other institutional investors (including other public pension funds) opened their wallets, and KKR was on its way. On its website, KKR marks 1982—when Oregon was joined by the Washington and Michigan public pension funds—as a milestone in its history. The special relationship between the Oregon fund and KKR continues today. George Roberts, one of KKR’s named partners, told the Oregon pension board in 2013, “You all are our longest standing partner. We always start with you.”

Over the 1980s, the wave of leveraged buyouts pioneered by KKR helped transform the business landscape dramatically, contributing to workplace speedup (an increase in productivity but not pay), union-busting and downward worker mobility. The movement hibernated in the 1990s only to be reborn in the 2000s under the name “private equity.” But the strategy remains the same, as do its effects.

In late 2016 and early 2017, for instance, unionized workers (represented by the Communications Workers of America) at Momentive, a chemicals manufacturing company in upstate New York, went on strike after the company tried to cut pay and health benefits, as well as eliminate pensions and health benefits for retirees. Momentive brought in scabs during the strike, a tactic the union says is responsible for a dramatic spike in oil and chemical spills during that period.

The private equity firm Apollo Global Management had bought Momentive from General Electric in 2006. Before the buyout, a job at Momentive’s 75-year-old plant was the best you could get in the small town of Waterford, N.Y., workers told the New York Daily News during the strike. “My dad worked here for 38 years, it was a great job,” said one employee. He and his brother had followed in their father’s footsteps, expecting that they, too, would make a good living.

After the buyout, however, the new owners put the squeeze on workers. Also holding an ownership stake in Momentive until summer 2017 was another PE firm, the Blackstone Group (whose head, Stephen Schwarzman, served a brief stint as Trump’s “job czar”). Under Apollo and Blackstone, management implemented a “restructuring” plan that had as its goal trimming expenses by $35 million. The restructuring, which is typical of companies bought by PE firms, included the slashing of worker benefits that triggered the strike.

In January 2017, striking workers came to New York City to rally in front of Apollo’s offices. They could also have rallied in front of the offices of the New York City pension fund, which has invested over $1 billion with Blackstone since 2003, and almost $650 million with Apollo. (Unsurprisingly, Oregon’s pension fund has invested $600 million with Apollo and $850 million with Blackstone.) In February 2017, Momentive workers ended their 105-day strike, accepting cuts in health benefits and vacation time for current workers, as well as the elimination of health insurance for retirees.

That is only one example.

In 2016, Elliott Management, a hedge fund that is particularly aggressive in seeking job-killing “restructuring,” and Francisco Partners, a private equity firm, acquired the software company Quest from Dell. The new owners announced layoffs the very next day.

The bloodletting continues. As this issue went to press, Israeli software development company Sintec Media, acquired last year by Francisco Partners, announced it was laying off dozens of employees as part of a “restructuring” process. And employees at MyWebGrocer, an online grocery store based in Winooski, Vt., owned by Palo Alto-based private equity firm HGGC LLC, lost jobs in another—you guessed it—“restructuring.”

Above: The Federal Reserve estimates there’s a $1.7 trillion gap between what state and local pension funds in the U.S. have promised and what’s been set aside. And that’s on the optimistic assumption of a 7.6% interest rate.

Enriching the Rich

Alternative financial instruments wreak additional social havoc by nourishing the political agendas of private equity and hedge fund billionaires. Many have invested heavily in the privatization of public institutions like schools and prisons. Hedge funders founded Democrats For Education Reform (DFER), an anti-teachers-union group. Hedge funders and other financiers sit on the board of directors of its parent organization, Education Reform Now, and have poured billions into both groups. Almost every time a charter school opens, it represents a decertification of a teachers union, as the charter school movement aims to replace traditional public schools with its nonunion model, which is precisely what attracts hedge funders to the charter school cause.

Public employees’ pension funds thus fund the destruction of not only the livelihoods of private sector workers, but their own unions, which are, of course, the reason public employees enjoy any benefits at all.

Teachers unions have pressured a few hedge fund managers into halting their involvement in school privatization. Cliff Asness of AQR Capital Management and Thomas McWilliams of Court Square both stepped down from the board of the Manhattan Institute, for example. Thus, while union pension funds may enjoy a bit of influence now and then, that doesn’t alter the fact that the entire model of “alternative investment” is set up to enrich a financial elite at the expense of the working class, public employees and the public at large.

The contradiction of pensions investing in private equity—that is, workers relying on worker exploitation to fund their retirements—is a distillation of the illogic of workers investing in Wall Street. The economic fate of workers gets tied to the performance of the stock market, a market that rewards companies for vicious assaults on the working class and accelerates the upward flow of wealth. According to NYU economics professor Edward Woolf, the “explosion” in the ranks of the very rich is “directly related to the surge in stock prices.”

In addition, investing in hedge funds and private equity gives union members an identification with the interests of the 0.1 percent, rather than each other. Private pension systems thus help undermine solidarity, the foundation of any hope for working-class power. For example, current and retired New York state workers identify each other in conversation by which of the six tiers of the pension system they belong to. Obviously, the 401(k)-ization of the system would further undermine solidarity, as the performance of one’s individual portfolio becomes a center of attention.

What is to be done?

The Right’s answer is clear. In a paper published by the (Koch-funded) Mercatus Center at George Mason University, John Dove and Daniel Smith (the fellow whose mission it is to bring down the Alabama pension system) recommended switching new state employees from pensions to “more portable and customizable retirement benefits.” Translation: The state would contribute a fixed amount to a 401(k)-like account with no guarantee of how big your pension check would be. This is similar to some right-wing schemes to privatize Social Security by creating individual retirement accounts for each worker.

As we’ve observed, labor leaders across the board have been evading the issue, with notable exceptions like AFT President Randi Weingarten and longtime SEIU organizer Stephen Lerner. Labor leadership recognizes the loss of members’ pensions is a looming crisis, but it’s not an easy issue to organize members on, and it certainly doesn’t lend itself to a media-savvy bid for public sympathy. One union employee in a Midwestern state (who requested anonymity since his union hadn’t authorized him to talk about the issue) described the pension crisis as “a real problem that was caused by short-sighted politicians and unions that enabled them.” The obvious solution—that rich people should be taxed more to fund public workers’ retirement—is a solid labor talking point, but it’s hard to publicly discuss without running afoul of the unpleasant realities: trillions in undeliverable promises, and city and state governments about to go belly up.

Instead of debating rates of return, we should look to transform the pension system itself. We need to free it from the snares of the financial markets and turn it into a real public benefit instead.

Michael McCarthy writes in Dismantling Solidarity: Capitalist Politics and American Pensions Since the New Deal that the current pension system—created during the New Deal—was not labor’s first preference. Instead, unions wanted an expanded Social Security system. “Funded” systems—vast pots of money invested in financial markets—were the best they could get.

It’s time to go back to Plan A: Let’s strengthen Social Security, a system that works well but isn’t expansive enough to fully fund retirements. Unions should make that expansion a primary political demand, backed up with the argument that the more employed and prosperous everyone is, the more robust Social Security will be.

In recent years, scaremongers on the Right have been telling Americans that the Social Security program is a “Ponzi scheme.” In fact, Social Security is the opposite: Everyone who pays into the system is guaranteed money when they retire. The system is based on the reality that there will always be another generation of workers to support the current generation of retirees, and, in fact, notwithstanding a birthrate panic now and then, there always are.

Our society as a whole can only guarantee its future security through social and physical investments. Investing in the stock market achieves the opposite; it expands the wealth and power of Wall Street, which likes tight budgets and low levels of public spending. When we instead put people to work building public infrastructure, when we have strong education systems and robust healthcare, and when we have strong unions and decent wages, we create a prosperous society that can fund a comfortable retirement for everyone.

Now is the time to fight for big, universal government programs that benefit all working people, rather than accepting grudgingly provided scraps for a fortunate few. The 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign, the explosion in membership and organizing of the Democratic Socialists of America, and the ascendance of Medicare for All as a political demand (supported even by some pretty dismal neoliberal Democrats) all suggest momentum moving in a left direction.

Workers of the world, divest!

is a financial journalist and the author of Wall Street: How It Works and for Whom (Verso), among other books. He is the host of Behind the News, a weekly radio show on economics and politics broadcast on KPFA and worldwide.

is a labor journalist and the author of Selling Women Short: The Landmark Battle for Workers’ Rights at Wal-Mart (Basic), among other books. She is a columnist for amNY and a contributing editor at The Nation.

Want to stay up to date with the latest political news and commentary? Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter:

Above: Striking workers picket at the Momentive factory in Waterford, N.Y., Jan. 13, 2017, protesting cuts in benefits after a private equity firm bought the company. (Photo by Will Waldron/Times Union)