The Two-Party System Is Facing Its Biggest Challenge In 70 Years

From Maine to Missouri, states are bucking the establishment to push radical electoral reforms.

March 19 | April Issue

We are in a moment of nervous, semi-panicked reflection about the health and prospects of the American political system. Take The Atlantic’s March essay, “America Is Not a Democracy.” It begins with the story of how a private water company in Oxford, Mass., apparently derailed a public buyout pushed by locals who were angry about high rates and poor service. The plan was voted down at a town hall meeting mysteriously packed with people who had shown little previous interest. “Even in this bastion of deliberation and direct democracy,” writes Yascha Mounk, “a nasty suspicion had taken hold: that the levers of power are not controlled by the people.”

With good reason. Polling shows that Congress is profoundly out of tune with the will of the people on almost every issue, from gun control to single-payer healthcare to action on climate change. In a Gallup poll released this past fall, only a third of respondents said the two major parties “do an adequate job of representing the American people.” Sixty-one percent thought a third party was needed—the highest number in eight polls taken over 15 years.

One path forward is to engage each issue and press for change within the existing dysfunctional system. But if there is a game-changing and achievable solution that solves some of the most profound problems at once—ending the stranglehold of the two major parties, multiplying the representation of minority voters, decreasing polarization and boosting voter engagement—doesn’t it deserve serious attention from progressives?

Such a solution—proportional representation (PR)—is already used in 94 democracies around the world. In those countries, there are more parties to choose from. Elections focus more on issues and less on individual candidates. The power of money is diluted, because coalition building takes priority over personal attacks. And there are more women and minorities in office.

In the United States, a semi-hidden history attests to PR’s transformative power. Introduced into the New York City Council elections in 1936, PR unleashed a wave of democratic engagement and diverse representation. Communists and other minority parties claimed 50 percent of the seats and broke the Democratic machine’s monopoly. In Cincinnati in 1951, PR put an African-American attorney, Theodore Berry, on the cusp of becoming mayor, until the establishment closed ranks and shut him out. A total of 24 cities adopted PR in the early decades of the 20th century.

The Red Scare, coupled with racism, squashed those experiments. New York City abolished PR in 1947, largely because it empowered Communists. Cincinnati did so in 1957, to block the rise of African Americans on the city council.

Now, in response to growing the glaring failures of our democracy, PR is being advanced at the local level from Maine to Missouri to California.

HOW IT WORKS

The biggest barrier to PR today may be inertia. Polling shows that its appeal transcends ideology, but the two-party tug-of-war is so ingrained that it’s hard to imagine a different way.

PR also has a marketing problem. Its name seems designed to make eyes glaze. And there are endless variations on how it could be implemented.

But set aside the marketing problems and the mechanics, and briefly consider PR’s basic claims.

The case for PR holds that the maddening things about American democracy are built into our legislative maps and our voting procedures; dysfunction and disenchantment are features of our electoral system, not bugs.

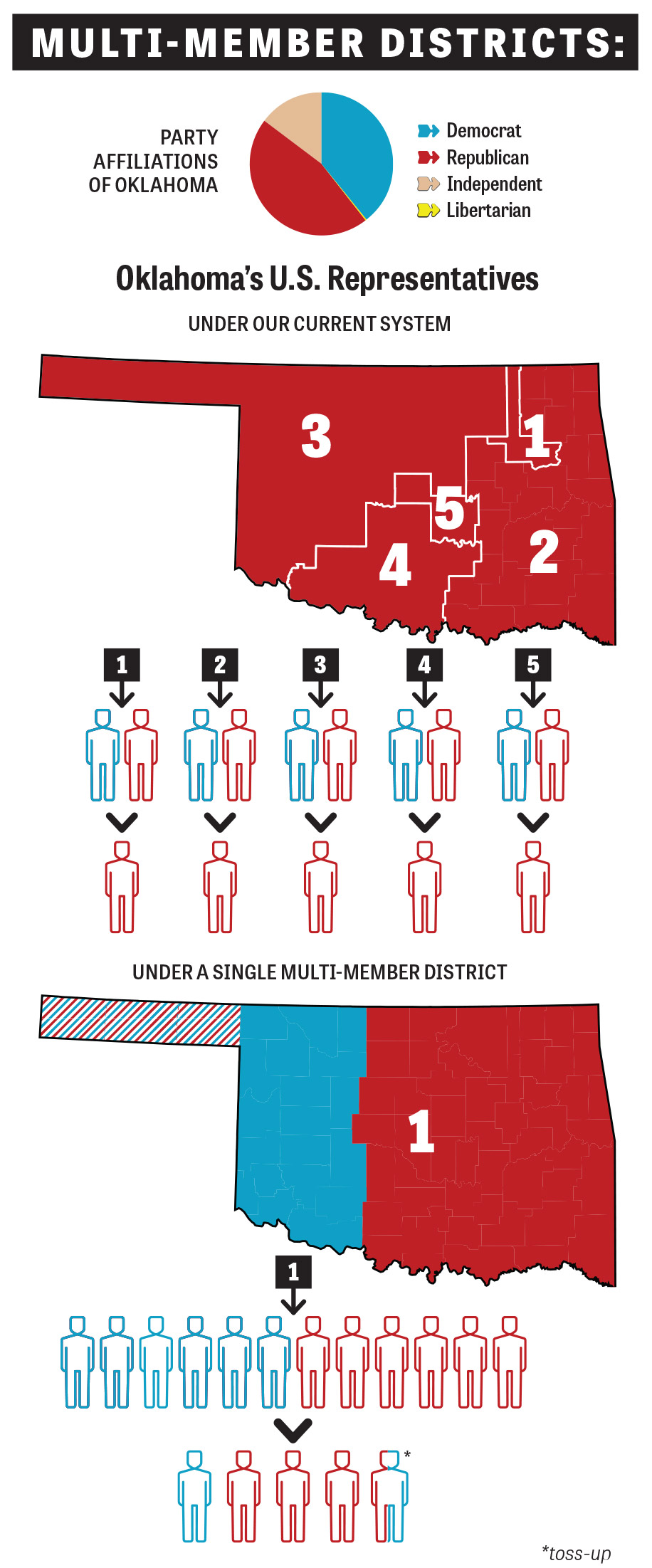

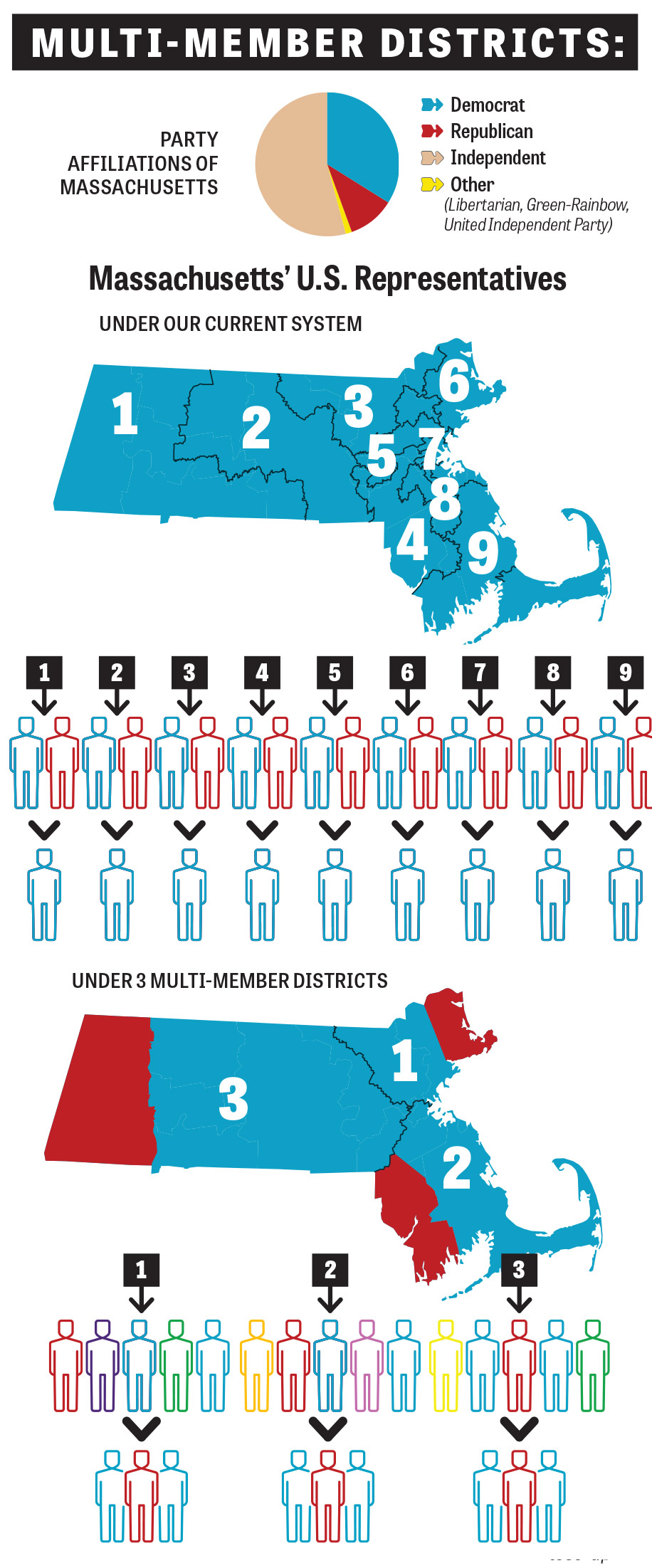

Districting maps courtesy of FairVote. These are computer-generated maps and do not represent an in-depth redistricting process, which would take into account communities of interest and cultural regions.

The basic principles of reform are simple. The first is that a legislative district need not be the domain of a single representative, but should be represented by multiple people—a reform called multi-member districts. The second is that voting should be about ranking the candidates, not choosing the single best person—a reform called ranked-choice voting (RCV).

Multi-member districts can create space for racial and ideological minorities, who may have trouble winning more than half the vote but can attract a loyal bloc, enough to come in second, third or fourth and earn a seat. Multi-member districts also defy gerrymandering. In a single-member district that’s split 60-40 along party lines, the 40 percent minority gets no representative. A ruling party can game the system by creating many such slim-margin districts in its favor, disenfranchising a sizable portion of the opposing party’s voters. But in a multi-member district, the 40 percent gets a share of the seats.

RCV breaks the grip of the two-party system in another way, by solving the problem of spoiler candidates and boosting voter engagement. In RCV, a voter’s second-choice candidate receives her vote if her first choice is eliminated. The same is true for her third choice if the second choice is eliminated. And so on. If the 2016 presidential election had been non-partisan and ranked-choice, Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton voters could have been at peace, knowing that by marking the other Democrat as their second choice, they would still be casting a vote against Donald Trump—even if their first choice didn’t win.

These two ideas can be applied independently, but they’re more powerful in combination. Alone, multi-member districting has some risks. For instance, under certain circumstances, it can actually suppress rather than increase minority representation (if “block” voting allows one party to win all the seats). Ranked-choice voting corrects that. Used together, multi-member districts and RCV dissolve the two-party monopoly and give outsider candidates a real chance.

A perfect storm of dysfunction, corruption and diminishing democracy is driving the recent revival of support for PR. The GOP’s radical gerrymandering of legislative districts, and the flood of corporate dark money since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision, have spotlighted how our political system is rigged against democracy in favor of wealth and power. (That’s in addition to Donald Trump’s constant laments about the rigging of the system and his incessant efforts to rig it for himself.)

In that grim context, PR’s bold and hopeful vision for how our system can work better is gaining traction and winning converts. It’s a solution well suited to this moment of democratic dysfunction and a flowering of local experiments.

“We’re in a crisis whose depth is not fully understood yet,” says Rob Richie, executive director of FairVote, a national advocacy organization working to promote PR. “People are hoping they can fix it with Band-Aids, and I don’t think they can. And as that sinks in, more and more people will see that PR bends things toward the changes that we need to make.”

A crusade in missouri

Several cities and states are now exploring one or both reforms. On June 5, Santa Clara, Calif., (pop. 126,000) votes on a measure that would establish both multi-member districts and RCV for city council elections. On June 12, Maine votes on a referendum that would establish RCV for state and federal offices.

The Santa Clara bill would mark the first time a city has adopted multi-member districting and RCV since the 1950s. Only Cambridge, Mass., currently elects its city council using RCV in multi-member districts.

The elections in Maine and Santa Clara are bellwethers that proportional representation is gaining momentum. A nascent effort in Missouri captures the kind of passion and faith it can inspire.

In late 2014, a retired high school economics teacher, Winston Apple, drafted a ballot petition that would create a PR system for Missouri’s state government. It didn’t get enough signatures the first time around, and he filed it again in late 2016. Since then, he’s been working to build support for it by coordinating with progressive groups around the state. They need about 160,000 signatures by May 6 to put it on the November ballot.

Apple is a member of Our Revolution and a self-described “political revolutionary.” He’s also a candidate for Congress in Missouri’s 6th District.

He originally wanted to put seven reform measures on the ballot this fall. When his coalition partners asked him, for the sake of simplicity, to choose one, he chose PR. “If we can get that on the ballot and passed this year, then in 2020 we will elect a genuinely democratic legislature that will pass all the rest of the ballot measures,” Apple says. “It’s a gateway to getting all the rest of the good stuff done.” His coalition partners include several chapters of Our Revolution and members of minor parties that would benefit from a PR system, including Greens and Libertarians

Most reform initiatives, like the one in Maine, push for only ranked-choice voting rather than full PR, because RCV is more familiar and less disruptive. Apple’s petition does the opposite. It would create eight larger state legislative districts, each with 10 representatives, cutting the total number of House seats approximately in half.

Winston Apple is on a crusade to redraw Missouri into multi-member state legislative districts. (Photo by Emily Burke)

Apple proposes a “list” system similar to the parliamentary democracy of many European countries. Voters cast their ballot for a party, not individual candidates. Parties fill their share of seats in the legislature according to the results of their primary elections. If a party wins three seats in a district, for example, the party’s top three primary vote winners are seated.

Apple, who’s from Independence and bears a bit of a resemblance to Harry Truman, says he designed it that way because it puts the focus on issues, not personalities. He has a Midwestern earnestness, and he approaches his role of political revolutionary with the energy of a convert. He’s written “a manifesto for the reform of public education,” Edutopia, and he’s working on a book about Keynesian economics that argues the federal government should become the employer of last resort.

For his mission to change Missouri’s electoral system, he’s created a website, GovernmentByThePeople.org, with two short videos that explain the basics of proportional representation, in addition to essays that describe it in painstaking detail. And he takes his cause on the road. In early February, he went to a three-day summit called “Unrig the System” at Tulane University in New Orleans. The summit’s goal was to “convene the brightest minds from the Right and Left to fix American politics.” The slate of speakers included both Nina Turner, president of Our Revolution, and Steve Hilton, a Fox News host.

People not formally scheduled to speak at the summit had a chance to pitch their ideas for a brief talk. Attendees voted on the pitches, and the winners got to speak at an event on the last day. Apple was among the winners.

“I think I convinced a whole lot more people that if we can only make one change, proportional representation is the one we should make,” he says. “It’s just a numbers game. The vast majority of people have no idea what it is or how it works. I’ve found that if you say, ‘This will break the two-party monopoly, and independent candidates will have a fair chance of getting elected,’ they say, ‘Where do I sign?’ ”

Maine leads the way

FairVote expects that the Missouri initiative will be a hard sell, especially the idea of voting for a party’s slate rather than individuals. “I tend to be skeptical that a list system will be successful in the U.S,” says Drew Spencer Penrose, FairVote’s law and policy director. “We’re used to voting for candidates, and we’re also used to big tent parties.”

Penrose and Rob Richie believe the path to victory for PR is a series of city and state-level reforms that evolve into a movement for federal PR over the next decade or so. A bill already in the House, the Fair Representation Act, would implement both multi-member districts and RCV. It currently has only four co-sponsors but serves to keep the item on the agenda for a future, more progressive Congress.

The referendum in Maine would establish ranked-choice voting for all state and federal elections, which is a more modest and less disruptive reform than combining it with multi-member districts. Think of RCV as the gateway to full PR.

Graphics adapted with permission from City of Minneapolis.

RCV has strong appeal in Maine because of the spoiler problem that’s plagued its recent gubernatorial elections. In the most recent election in 2014, Democrats and Independents split their votes between two candidates who got 43 percent and 8 percent of the vote, respectively. The result was the re-election of the radical right-wing Republican governor, Paul LePage, with 48 percent of the vote. LePage, known for spouting racist paranoia about out-of-state drug dealers (“half the time they impregnate a young white girl before they leave”), comparing the IRS to the Gestapo and telling the NAACP to kiss his butt, earns consistently low approval ratings. He almost certainly would have lost under a ranked-choice voting system, since he likely wasn’t the second choice of people who voted for his challengers.

San Francisco adopted RCV in 2004, and three more California cities followed in 2010. A FairVote analysis found that the percentage of people of color winning office in those cities rose from about 41 percent prior to implementation of RCV to nearly 60 percent afterward. In all, 12 cities nationwide now use RCV in municipal elections. Santa Fe, N.M., used it for the first time in March.

The path to RCV in Maine shows how its establishment-busting power both threatens the two parties and galvanizes grassroots support. Maine voters first approved the system’s use in 2016. Republicans and some Democrats in the legislature joined forces (citing a complicated Maine Supreme Court ruling) to delay implementation until 2021. But in Maine, voters can repeal recently passed legislation through a “people’s veto.” Advocates for RCV used that provision to put it back on the ballot in June.

All the drama around RCV has likely helped its chances in Maine. As FairVote’s Penrose points out, “We’re not only seeing people who want ranked-choice voting, we’re seeing people outraged at the state legislature for trying to thwart the will of the people.”

A June win in Maine would take effect in November, making it the first instance of RCV’s use in Congressional elections, and establish a state-level model for how the United States can begin moving toward a better system.

“The first statewide use would be a sea change,” Penrose says. “You’d be able to point to a place that’s already using it. I could just say, ‘It’s the Maine system.’ I think we’d start seeing the impact right away.”

Gerrymander no more

It’s curious bordering on bizarre that proportional representation doesn’t attract more interest and resources from progressives. It cuts the Gordian knot of entrenched problems in U.S. politics, achieving many of the movement’s most cherished goals, notably by increasing representation among minority populations and by making votes for third-party candidates more relevant. In an era that’s been defined by playing defense, it offers a realistic plan for democratic revitalization that flips the script on the GOP’s anti-democratic impulses.

Gerrymandering is a classic example. Progressives and Democrats have been doing triage and playing catch-up on this front since the electoral tidal wave of 2010, when Republicans won control of a majority of state legislatures and used that power to gerrymander districts and dominate every level of government.

Some hope is on the horizon: Courts have ruled recently that the GOP-drawn maps in several states—Texas, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and North Carolina—are unconstitutional. And Barack Obama and his U.S. attorney general, Eric Holder, have turned gerrymandering reform into a high-profile issue.

But for supporters of proportional representation, the problem is deeper than the way districts are drawn. The problem is that single-member districts are inherently vulnerable to deck-stacking. And the solution isn’t simply to redraw them.

“There’s so much simplistic analysis of the problem, because people want it to be fixed easily,” FairVote’s Rob Richie says. The attitude is that “we just need to fix gerrymandering, and the two party system will be fine. And we don’t have to really change things. We can just kind of pretend. But that’s fake. We’re in a moment where this is an inescapable conversation. We just have to prepare for that, and show the path.”

The June votes in Santa Clara and Maine will indicate whether the push for proportional representation is gaining traction. Whatever happens with those votes, though, and even if Winston Apple’s effort to get his initiative on the ballot in Missouri falls short, PR is beginning to sink roots in America. That it will grow and flourish isn’t inevitable, but it may offer our best hope for tapping the kind of transformative democratic energies we’ve been searching for.

“I’d like to reform the government by tomorrow afternoon and be at 100 percent renewable energy by 4 o’clock,” Apple says. “But we’re going to have to be more patient than that. And I think proportional representation, honestly, is the biggest issue that we can deal with right now. In the states where we can get it passed, those states are going to have genuinely democratic elections. And be the envy of the rest of the country.”

, a Chicago-based writer, has contributed to In These Times since 2010, covering the progressive movement’s engagement with electoral politics and the history and development of the Right. His doctoral dissertation at Yale traced the early 20th-century origins of the progressive and conservative movements.

Want to stay up to date with the latest news and political stories? Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter: