Soldiers with Somali’s Danab battalion, which is specially trained by the U.S. military, stand in formation at a logistics training graduation ceremony. (Photo by MC2 (SW/AW) Evan Parker / AFRICOM)

U.S.-Assisted Raid in Somalia Killed Two Civilians, Villagers Say

The testimony provides a rare window into U.S. ground operations in Somalia

September 4, 2019

James Ali Khamis remembers the three men clearly. They wore masks and head-to-toe olive-green uniforms. When their headlamps shined in his eyes, he couldn’t make out their faces. One man spoke what sounded like English, another spoke only Somali, and the third translated. All were armed.

They broke down the door to Khamis’ house in the village of Shanta Baraako, in the Lower Shabelle region of Somalia, in the middle of the night with an explosive to the first door and two kicks to the second. Then they took Khamis, hooded and handcuffed, to his brother-in-law’s house. Twelve people were in a lineup there.

The men pointed their lights down the row, bringing each face out from the darkness. The Somali speaker asked Khamis if any of them were who they were looking for, Abdikadir Sufi. Sufi, allegedly a Kenyan-Somali tax collector for al-Shabab—the Somali militant fundamentalist group loosely aligned with Al Qaeda—had been hiding out in this house for the past four months.

Halfway through the questioning, the interrogation was interrupted by noise and footsteps from some of the other dozens of soldiers who had driven to the village that night.

Khamis heard the Somali words “Stop! Stop!” Then a voice in English. Then the Somali word for “shoot” and then, not so much the pop of a gun, but a millisecond sharp blast of heavy wind.

Two of the three left the house, seemingly to see what happened. They came back minutes later to hastily finish the questioning. Sufi was not there. Then they added Khamis to the lineup and brought in two more men to question.

When it was over, Khamis rejoined his family. His wife had vomited from anxiety and his 7-year-old son had passed out from fear. Khamis, a village leader, spent some minutes checking to make sure everyone in the community of about 10 total households was safe. His sister Waliyo Cali Qaasim was missing.

A search party found her less than 10 minutes later, lying by the side of the road.

“It looked like she was sleeping,” Khamis says. He rushed to her. Her body was already cold. She had been shot to death. The gun apparently had a silencer, muting the crack of the shot into that whisper of wind.

According to Khamis, the only eyewitness to the shooting is a teenage boy. The boy's father would not let his son be interviewed by In These Times, but Khamis spoke with the boy and his father about what he remembered from that night; he says he saw Waliyo run out of her house, yelling, seemingly panicked, then hit the ground following the shot.

Waliyo was not the village’s only death that night. Abdikadir Ali, a watchman in his mid-thirties, was shot and killed while patrolling a farm.

James Ali Khamis brought Somali authorities a photograph of his sister, Waliyo Cali Qaasim, taken after her death.

In an email to In These Times, U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) confirmed that their forces were with Somali troops July 12 near Shanta Baraako. A spokesperson said its forces were on the mission to “advise and assist” and “did not engage in direct action of any kind” during this operation. U.S. operators serving in an advise-and-assist capacity, go on missions with Danab, the Somali Special Forces they have been training since 2013.

AFRICOM referred In These Times to the Somali government for questions about Danab’s activities, but the Ministry of Defense does not have a clear point of contact, and neither the Office of the Prime Minister nor the Office of the President responded to multiple email requests for comment about allegations of civilian casualties.

But rare insight into U.S. ground operations in Somalia can be gleaned from separate interviews conducted with four Shanta Baraako residents home the night of the July 12 operation.

Interviews with Khamis’ wife, Rahmo Abukar Mohamed, who was herded from her house and held at gunpoint with her children, and Khamis’ younger brother, Hassan, who was outside watching his cows and fled to lay in an irrigation canal when cars of armed men pulled up, corroborate Khamis’ account of the event’s timing and operational process.

Mohamed Hussein Abdalle (nicknamed “Barre”), who was with Ali when he was killed, described that encounter to In These Times. He said Ali was shot running away from Danab. Pictures shared with In These Times show Ali had been chewing khat when he died—an addictive, chewable stimulant banned by al-Shabab—which suggests Ali was a civilian.

With no mechanism for reporting civilian deaths and no clear lines of responsibility and culpability on the battlefield—further compounded by a complex local context—these advise-and-assist operations are ripe not only for politically motivated actors to give bad intelligence or intentionally mistranslate, but for unaccountable, deadly misunderstandings.

Soldiers with Somali’s special forces Danab battalion await their diplomas after a 14-week logistics training with the U.S. 10th Mountain division. (Photo by MC2 (SW/AW) Evan Parker / AFRICOM)

The U.S. kept Somalia at arm’s length after the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu (made infamous by the book and film Black Hawk Down) two years into Somalia's knotty civil war, an ongoing power struggle that started after the 1991 overthrow of dictator Siad Barre. Years of chaotic fighting, underpinned by clan alliances, saw the rise of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), a unified coalition of Sharia courts. The ICU formed a rival government in opposition to Somalia’s comparatively messy, internationally backed Transnational Federal Government. Still reeling from 9/11 and wary of any sort of Islamic political leadership, in 2006 the U.S. supported neighboring Ethiopia to invade Somalia by proxy and bring down the ICU. It went quickly, but the Islamist guerrilla group al Shabab grew in power after the ICU’s demise.

Even though al Shabab’s original leadership was mainly comprised of Somalis trained in Iraq and Afghanistan, the average al Shabab foot soldier has no real connection to the international jihadi movement.

“My research interviews support that al Shabab is a deeply local organization and that their aims are much more focused on securing a state in ‘Greater Somalia’ than in waging global jihad,” says Katharine Petrich, a visiting researcher at the University of Albany’s Center for Policy Research. “Obviously every politically violent Islamist movement is deeply informed by their local context, but al Shabab has shown no interest in carrying violence outside the Horn of Africa region, despite having the networks in the diaspora to do so.”

Even as al Shabab carries out attacks across East Africa (most famously killing more than 65 people at an upscale mall in Kenya's capital, Nairobi, in 2013, and more than 20 at an expensive Nairobi hotel in January), the group maintains a nationalist focus: It is at war with the Somali government, named the most corrupt in the world by Transparency International for 13 years running.

The U.S. began a campaign of selective, secretive air strikes against top al Shabab brass in 2007. Boots quietly hit the ground in 2013 in the form of Danab trainers and advisors, and U.S. military involvement has become increasingly direct and public. In 2017, President Donald Trump declared large swaths of Somalia to be areas of “active hostilities” and the U.S. tripled the number of air strikes, many of which targeted Lower Shabelle.

Danab has made significantly more gains against al Shabab than the Somali National Army, which is still struggling to find unity and direction. Paul Williams, a professor at George Washington University who studies warfare in Africa, says Danab is central to the fight against al Shabab not just operationally, but symbolically.

“Their multi-clan and meritocratic composition showcase what could be achieved if Somalia developed professional military forces complete with proper training, equipment, financial support and field mentoring,” Williams wrote in an email to In These Times.

While AFRICOM has stated repeatedly to the media that all of its missions have been Somali-led, conversations with sources in the Somali government make clear that Americans—and the funding they bring—have the upper hand.

Asked how much responsibility the U.S. military takes for Danab’s actions during “advise and assist” missions, AFRICOM responded, “Partner forces, as independent and sovereign entities, are responsible for their actions.”

In April, AFRICOM made its first and only avowal that two civilians had been killed by its strikes, in 2018. Otherwise, the U.S. has denied all of the accusations of civilian casualties made by international reporters and by Amnesty International, whose investigation into five other U.S. air strikes determined they had caused at least 14 civilian casualties.

A Daily Beast investigation found “strong evidence” that U.S. soldiers murdered 10 civilians on a joint operation with the Somali National Army in August 2017 in Lower Shabelle when they waded into an inter-clan conflict with a translator who had a history of suspected manipulation of U.S. forces. A U.S. investigation is ongoing.

In September 2018, U.S. and Danab forces accidentally raided the well-known estate of a beloved former president. The Guardian reported that the Americans were relying on bad intelligence.

“International agencies and governments need to be careful about their Somali interpreters, as they potentially can cause problems,” says Abdisalam Guled, who was deputy director of Somali’s National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) from 2013–2017. “Inter-clan politics and conflict go with every wire in Somalia, and there’s always a possibility that someone could translate an order given in English to something else. Also, federal members of Parliament, as well as regional politicians may misuse their position of power to influence translators. Foreign operators must double- and triple-check their intel sources and translations before they make any commitment. This will save a life and resources.”

Translation may have been key to the operation in Khamis’ village. Khamis heard English just before the Somali command to shoot. That raises a question: Did a U.S. soldier say “shoot”? Or was that how the Danab translated what he said?

Soldiers with Somali’s special forces Danab battalion await their diplomas after a 14-week logistics training with the U.S. 10th Mountain division. (Photo by MC2 (SW/AW) Evan Parker / AFRICOM)

A Ugandan soldier with AMISOM moves through the city of Bulo Marer in Lower Shabelle, Somalia, on August 31, 2014, on a mission to retake the town of Kurtonwarey from al Shabab. (Photo by Noe Falk Nielsen/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Civilians in rural Somalia, living amid warring insurgent, national and international forces, exist in a treacherous gray zone with changing laws and tax codes depending on who appears to be in charge. Since it was deployed in 2007, the African Union peacekeeping mission in Somalia (known as AMISOM) has taken back a substantial part of the territory that al Shabab once physically controlled, and now holds most main cities and towns. Some rural areas around the country, including the majority of Lower Shabelle, are still directly held by the fundamentalists. Others may be technically under government control but are heavily influenced by al Shabab.

Khamis’ village is in Lower Shabelle, the nation's fertile breadbasket, is a hot spot for insurgent and clan-based violence, valuable territory for any party to the lingering conflict. Farmers cultivate lemon tree plantations and mango and tomato farms along the banks of the Shabelle River. Merchants sell the produce from this lush oasis in Mogadishu and beyond. Lower Shabelle’s active economy and thick vegetation make the area especially attractive to al Shabab—as a large tax base with brush for protection. If there is an al Shabab stronghold in Somalia, it is Khamis' region. Not everyone in Lower Shabelle is loyal to al Shabab, but many of the residents acquiesce to its demands in order to maintain their farms and businesses.

“I think the population that lives in AS-controlled territory is largely interested in trying to live their lives, run their businesses and stay out of the fray from all parties,” Petrich told In These Times over email. “The impression that I have of the ‘average’ Somali living in these contexts is one who has seen warlords, clan leadership, government soldiers and international interventions come and go with such frequency that nobody is really committing to anything until they have to.”

The whole village of Shanta Baraako knew that Khamis’ brother-in-law—the husband of one of his other sisters—had been hosting Sufi. Khamis says that many in the community had been unhappy with Sufi’s stay and wanted him to leave, arguing (with correct foresight) that a mid-level al Shabab leader in their village made life more dangerous.

As Danab and the United States make headway in Lower Shabelle, they have become the subject of more and more accusations of civilian casualties and arbitrary arrests. Mahat Dore, a member of Parliament based in Marka, a main town in Lower Shabelle, has recorded six incidents in which civilians were killed and property destroyed since April 4.

“People are fed up with the Americans and Danab,” he says. “They are killing without excuse. They are arresting without excuse.”

According to Dore, people call him after a raid to report what happened. He also says he has visited prisons and villages to see dead bodies and damaged property. Dore claims that he sent a message to a Somali staffer at the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi. Dore also shared photos of the flash bangs made by the Pennsylvania-based company Combined Systems, which he collected from the villages. The police commissioner in Lower Shabelle knows what’s happening, Dore tells In These Times, but says the Somali government in Mogadishu “is not ready to advocate.”

A Ugandan soldier with AMISOM moves through the city of Bulo Marer in Lower Shabelle, Somalia, on August 31, 2014, on a mission to retake the town of Kurtonwarey from al Shabab. (Photo by Noe Falk Nielsen/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Somali MP Mahat Dore collected a “flash bang” explosive, made by the Pennsylvania-based company Combined Systems, from a village in Lower Shabelle after a U.S.-assisted raid allegedly damaged property. (Courtesy of Mahat Dore)

After daybreak July 13, Khamis, with his older sister, Hamsa, and Waliyo’s 22-year-old son, Mohamed Hussein, took a minibus to Mogadishu. Seats were removed to make room for a mattress to lay the two bodies.

Their first stop was the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), where they told the desk officer that people in armored vehicles had killed civilians in their village the previous night. Khamis says he spoke with one man who recorded what he said, took pictures of the bodies and wrote a letter to the hospital, requesting confirmation the two had died by gunshot wounds. Overall, CID seemed disinterested, Khamis says: “CID didn’t care if people were killed or grass was cut. It was the same for them.”

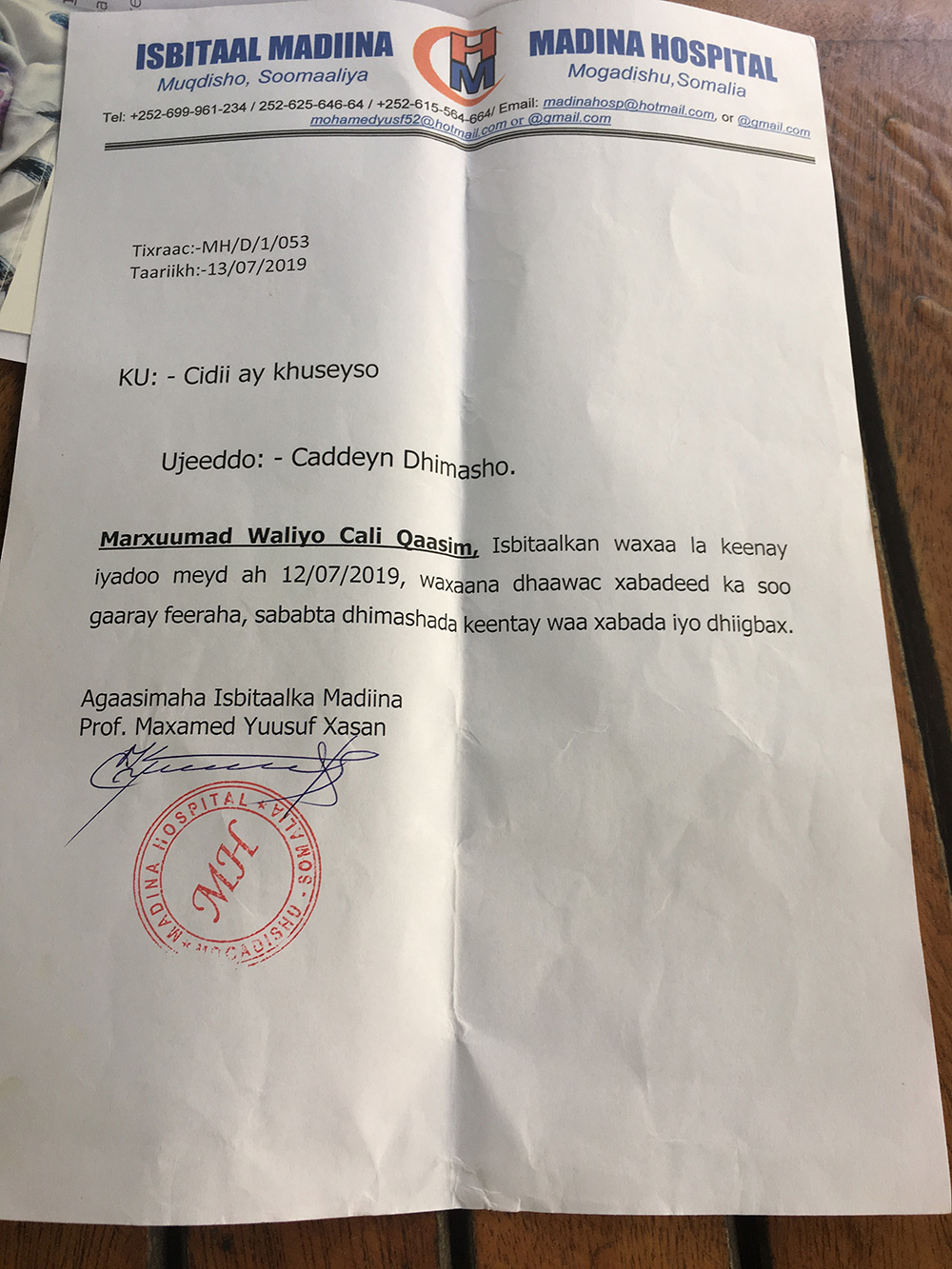

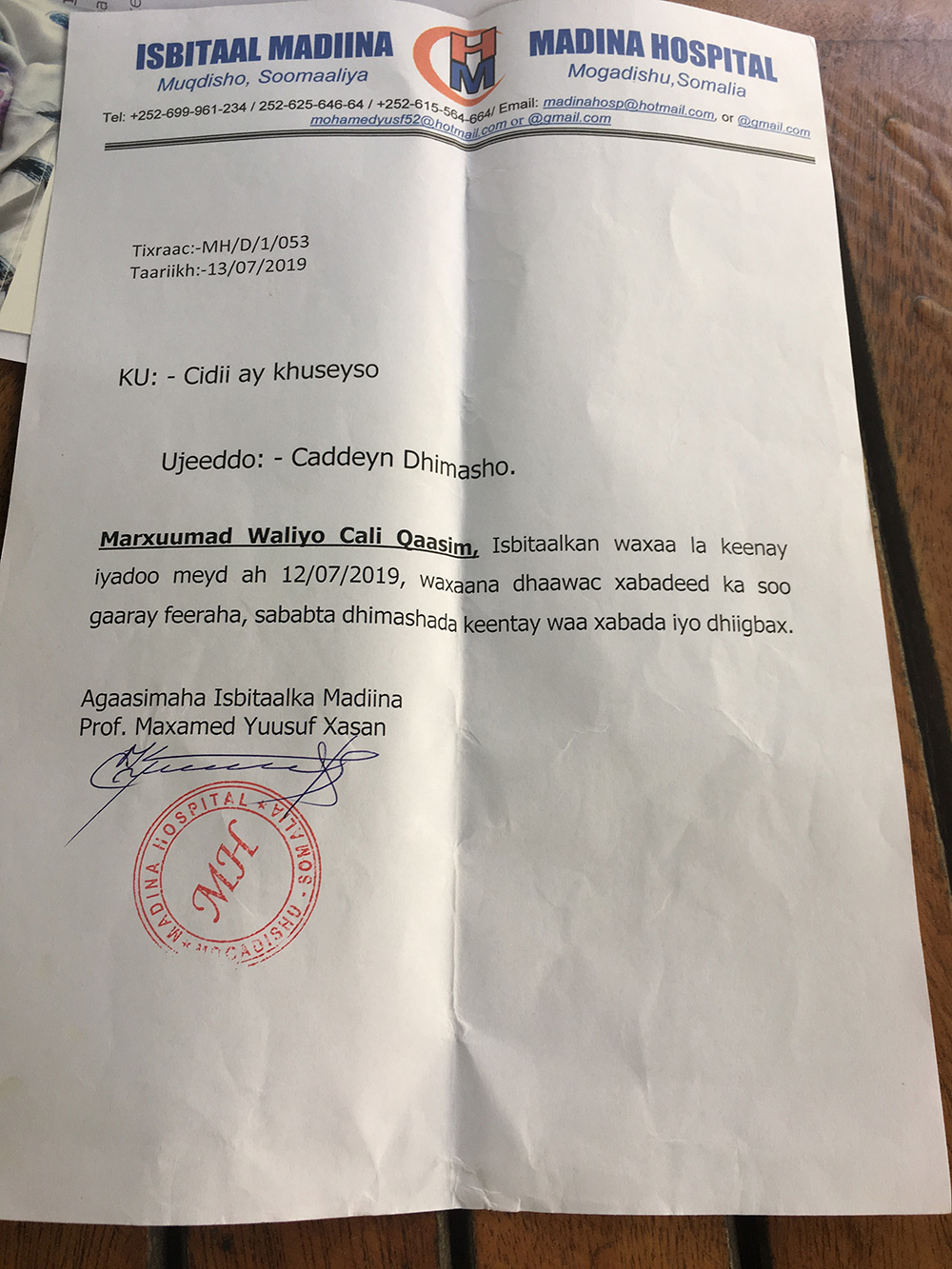

At the hospital, the bodies were assessed and confirmation letters were written. Madina Hospital dated Waliyo’s death certificate July 12. In These Times reviewed the certificate and verified it with the director of the hospital.

James Khamis brought his sister Wayliyo's body to the Madina Hospital in Mogadishu and obtained a death certificate.

Khamis says a friend staying in Mogadishu brought the hospital’s letter back to CID. The family returned home to bury the bodies.

Khamis was angry: He first believed that the D.C.-headquartered private security firm Bancroft, which also trains and operates with Danab, had killed his sister, and that something needed to be done.

Khamis was wrong about Bancroft, but he was right that the people on the ground with Danab were American.

Khamis says he has not heard any updates about his case from CID.

Daniel Mahanty, the U.S. program director for the nonprofit Center for Civilians in Conflict, believes that if the United States engages on the ground, it bears responsibility to ensure systems are in place to report civilian harm—especially in a place like Somalia, where the government and a justice system barely exist.

“The U.S. should do what it can to ensure that its partners have made channels available for the public to safely report harm and that steps are taken to assess and investigate any claims that are made,” Mahanty says. “This is especially true in Somalia, where the U.S. has arguably a greater responsibility given its role in developing the capacity of new security forces.”

Guled, the former deputy director of Somalia’s NISA, believes this concern should also be considered tactically.

“To be successful in their fight against al Shabab, the Somali government and their alliance need to have everyone on board in their operations against al Shabab,” he says. “They can’t win a war when everyone sees you as the enemy, which is the case for the Somali government and the U.S. at the moment.

“People will not feel liberated if they are scared of you or if they know you have killed someone they know.”

Asked what AFRICOM would advise the Somali government to do if there are allegations of civilian casualties during Danab raids, AFRICOM media relations chief John Manley referred In These Times back to the Somali government for comment.

Asked if transparent investigation into allegations of civilian casualties would help legitimize the Somali government, Manley responded, “I am not in a position to provide an opinion on a speculative question like this. Your question should be directed toward the Somali people.”

But Somalia’s Ministry of Defense seems to have little leverage and less information about Danab-U.S. missions, according to current and former government sources. This frustrates members of Parliament who look to the Ministry of Defense for updates about the war. One member of Parliament (aligned with an opposition party), who requested anonymity because of the sensitivity of military information, said the Parliamentary Defense Committee isn’t told—even after the fact—about operations. “Details of U.S. airstrikes and ground operations are limited,” he said. “After each operation, we were supposed to be kept abreast about civilian casualties, but we have never gotten the casualty details. The Defense Committee is responsible for the oversight and demands that a record of civilian casualties with a considerable degree of detail be shared with the committee.”

At a meeting in March, he says, the committee addressed the defense minister and his deputies about civilian casualties, following complaints a committee member had received about a recent incident, but the Ministry had no operational information.

“Accounts from people who witness these kinds of operations are very helpful to understanding of what is happening on the ground and how it might be affecting Somali communities,” Mahanty says. “There’s a lack of information about specific operations and the tactics that are used.”

James Khamis brought his sister Wayliyo's body to the Madina Hospital in Mogadishu and obtained a death certificate

Tommy Ross, a former deputy in the U.S. Department of Defense and senior advisor on intelligence and defense to Senate leaders, tells In These Times that “one of the most important concerns” about the “apparently growing reliance on advise-and-assist missions” is the “transparency of these sensitive operations and the combat situations into which they thrust American troops.” He adds that “unlike traditional combat operations, advise-and-assist missions in the post-9/11 context can place U.S. forces in harm’s way without any specific authorization or any congressional debate,” and that these missions can “trigger escalation or damage broader interests without being appropriately scrutinized or approved.”

The day after the burial, with no word from CID, Khamis brought his story to the chairman of the farmers of the Lower Shabelle, a man named Hassan Barkhadle. Barkhadle and Khamis attended a meeting that afternoon with member of Parliament in Mogadishu, held at a restaurant near the beach.

It was a crowded conference, according to Khamis, with, he estimates, more than 70 people sharing complaints about Danab and the Americans to the MPs. According to Khamis, when he showed the MPs the pictures of his dead sister and neighbor, they pushed the photos back across the table, not wanting to touch or acknowledge the documentation.

Khamis says the encounter was “demoralizing” and that he felt like he didn’t matter. He says the weeks spent seeking official acknowledgement of the incident were maddening. None of the government representatives seemed to care about a constituent's legitimate accusation about the country's most revered troops—trained by the Americans, no less. The process was a disorganized tour of various meetings with disinterested people.

Al Shabab, Khamis notes, is not nearly this sloppy.

is a journalist who travels between New York, Nairobi and Mogadishu.

This reporting was supported by the Leonard C. Goodman Institute for Investigative Reporting. Skyler Aikerson contributed fact-checking.

Never miss a story. Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter: