(Photo by Photo by Daniel Terdiman/CNET)

YIMBYs Exposed: The Techies Hawking Free Market “Solutions” to the Nation’s Housing Crisis

Anti-displacement activists hate them. Tech firms and big developers love them—and shower them with cash.

May 21 | June Issue

SAN FRANCISCO—Tensions over the housing affordability crisis were on full display at an April 3 rally against a California housing development bill, SB 827. Low-income housing activists, largely seniors and people of color, crowded the steps of San Francisco’s City Hall to protest a measure they believed would displace their communities.

When a white counter-protester, Sonja Trauss, waded into the crowd for a photo op next to their signs, she got into a physical altercation and was removed by a sheriff’s deputy. Trauss says she was shoved.

The 36-year-old has gained national acclaim as the founder of the YIMBY movement, as in “Yes, In My Backyard.” YIMBYs are self-described “grassroots, pro-housing” agitators who have become a major presence in high-cost, rapidly gentrifying markets like San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York City and Seattle. Their strategy is grounded in the free-market logic of supply and demand: Build more housing and housing costs will go down.

YIMBYs pose themselves as the antidote to the problem of not-in-my-backyard-ism. In San Francisco, that NIMBY stereotype has a basis in reality: “Concerned” neighborhood groups have, time and again, blocked new housing for reasons that range from aesthetic distaste to pearl-clutching about crime rates.

But as Trauss and her fellow YIMBYs chanted “Read the bill!” on the steps of City Hall, NIMBYs weren’t the target. Housing activists of color were. Charles Dupigny, the Black co-director of the group Affordable Divis (short for Divisadero, a major thoroughfare), shouted over the YIMBY noise: “I say to these individuals: Start doing some research, look into who actually gets those homes, look at ... who’s behind the bills.”

The San Francisco Examiner reported that a 77-year-old woman with the Chinatown Community Tenants Association “was so disturbed by the YIMBY shouting that she later fainted and was ferried by ambulance” to the hospital. “I think the YIMBY have no heart,” Association President Wing Hoo Leung told the newspaper.

Rally speaker Shanti Singh, a member of the local chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), tweeted afterward, “What I saw today happen to Black, Latinx and Asian activists from working-class SF communities when they tried to speak about their struggle ... was absolutely infuriating and pathetic. Shouted over by white people. Is there a more perfect encapsulation of our urban history?”

Though only about three years old, the YIMBY movement Trauss helped create has become one of the loudest voices in Bay Area and Los Angeles housing. YIMBYs regularly show up at city planning meetings, issue influential voting guides, sue local governments to overturn housing restrictions and have drafted controversial California housing bills, such as 827. he alifornia playbook is being duplicated lsewhere; the site YIMBY.wiki lists more than 100 YIMBY-identified groups in cities around the world, from YIMBY Uppsala in Sweden, to Better Boulder in Colorado, to Walkable Princeton in New Jersey.

YIMBYism has caught fire, in part, because of the need for housing solutions. According to the latest annual report of the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, one-third of people in the United States spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent or mortgages. In Los Angeles and New York City, that proportion rises to more than 44 percent of residents. In the YIMBY stronghold of San Francisco, it’s 38 percent.

YIMBYs seem to offer a straightforward prescription that doesn’t upend the free market, and national media outlets love it. In 2017, Politico named Trauss one of the “Politico 50”—people whose ideas are “blowing up American politics.” The Atlantic lauded the “progressivist” movement’s “cooperative” approach to working with developers. New York Times technology correspondent Conor Dougherty described the July 2017 YIMBY conference, a 200-person gathering in Oakland, Calif., as “like Woodstock, but for housing activists.”

But Trauss and the YIMBYs are a deeply polarizing force in the Bay. Rendered invisible by this YIMBY-NIMBY divide are the established housing advocacy groups that have been fighting the displacement of working-class communities of color for decades, like the anti-827 crowd at the April 3 rally. The Los Angeles chapter of DSA even coined the term PHIMBY—Public Housing In My Backyard—to represent this sidelined perspective. In San Francisco, these housing advocates are wary of the YIMBYs’ free-market bent, particularly when the movement is made up of so many young, white tech workers.

Maria Zamudio is an organizer with the Plaza 16 Coalition, an anti-gentrification group based in San Francisco’s Mission District. When she first saw the term YIMBY in 2016, she was interested—although suspicious of the homogenous whiteness of the group. She thought the “positive, solution-oriented” build-more-housing campaign helped demystify complicated issues like land use and zoning.

But she was eventually soured by Trauss’ racially charged comments. Trauss has publicly compared Latinx anti-gentrification activists to anti-immigrant Trump supporters, and tweeted that “gentrification is an unmitigated positive phenomenon for Black homeowners. Full stop.” She later deleted the tweet.

Zamudio now sees the YIMBY ethos as an oversimplification that doesn’t take into account the racist history of development: “They’re like, ‘Just build housing, you stupid brown people! I moved here last week, and I need a place to live!’ ” Zamudio has come to believe the YIMBY movement “is about developers and speculators who are starting to get a bad rap and need to rebrand themselves.”

In order to sort through the wildly divergent portraits of the YIMBYs, In These Times looked at the ideology, lobbying efforts and funding of Bay Area YIMBY groups. Are YIMBYs the misunderstood allies of anti-displacement activists? Or are they simply carrying water for developers who want to build housing for the wealthy at the expense of anyone else?

YIMBY leader Sonja Trauss (center) chats with Palo Alto Councilman Adrian Fine (L) and his wife, Jane (R), at a YIMBY Action fundraising gala Nov. 2, 2017, at San Francisco’s Verdi Club, where Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman was a featured guest. (Photo by Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

The oft-told YIMBY origin story goes like this: Trauss, a math teacher who lived in the gentrifying neighborhood of West Oakland, was frustrated by her high rent. She believed that San Francisco’s failure to provide housing for tech workers was having a spillover effect. In 2014, she began crossing the Bay to testify at planning meetings and recruited others to speak in favor of 300 new units in San Francisco’s Potrero Hill neighborhood.

Trauss’ early messaging sounded like hardline free-market capitalism: Deregulate and build. “I don’t want subsidized, supervised affordable housing,” Trauss wrote in 2015 for the Libertarian Party of San Francisco. “I want to consume housing the way I consume all other products.”

The message resonated with the tech industry, which helped launch Trauss’ one-woman crusade into a movement. In 2015, she received a personal gift of $10,000 from Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman, who told the San Francisco Business Times it was “ridiculous to blame companies—tech or non-tech—for rapidly adding jobs” and praised Trauss as representing “a massive segment of the population that’s been largely ignored in the discussion on Bay Area housing—renters.”

Trauss used the donation to, among other things, start the real-estate news and opinion website SFYimby.com, and to pay her rent. Stoppelman went on to donate at least $100,000 to the first YIMBY group Trauss founded, the SF Bay Area Renters’ Federation, or SFBARF.

There are now more than two dozen YIMBY-affiliated groups in the Bay Area, by YIMBY.wiki’s count. In These Times investigated the filings of three that are registered as PACs, which must disclose their donors by law: Yes in My Backyard, Affordable Housing for Teachers and Working Families, and the SFBARF PAC. Together, they have raised $377,000 since 2015, mostly in donations of $100 or $500.

Forty-three percent of that money came from employees of tech firms. The next-largest proportion, 10 percent, came from real estate employees. Architects, real estate attorneys and other PACs and YIMBY groups also showed up frequently in the donor rolls.

The tech money came from the middle or upper echelons of Silicon Valley. Donors included top executives at Cisco Systems, Palantir Technologies, tech incubator Y Combinator and cloud communications firm Twilio, as well as software engineers at companies like Google and Facebook.

In summer 2017, tech executives, including Microsoft’s Nat Friedman, gave half a million dollars to form the statewide lobbying group California YIMBY. By December, California YIMBY had raised nearly $1 million with Friedman’s help, according to the New York Times.

Asked about the tech industry’s donations, Trauss says that big employers like Google have “a workforce housing issue.” On this, she says, “workers and their employers are on the same page.”

Tech has also been a hotbed of YIMBY recruitment. Palo Alto-based engineer Max Kapczynski, 25, who moved to Silicon Valley in 2015 to work for Verily (formerly Google Life Sciences), estimates he now spends 8 to 10 hours a week promoting the YIMBY message. Though his efforts are largely online, he notes that his stable, well-paying job affords him time for advocacy: “I have the luxury of being able to leave at 5 or 6 and sit at a city council meeting for hours … before I make a public comment.”

California YIMBY co-founder Brian Hanlon (a former grant writer for the U.S. Forest Service) explained to real estate blog The Real Deal why he thinks techies are drawn to YIMBYism: “I think tech people are used to solving to [sic] hard problems. They’re used to thinking in terms of scale.”

Even for those outside of tech, it’s easy to see the appeal of the stated goal of YIMBYism—bring down the cost of housing through increased density. Where the YIMBY ethos conflicts with many housing experts’ opinions is the belief that more housing alone will bring down prices.

Market-rate housing often “actually creates its own demand,” writes Rice University urban planning professor Bill Fulton, in the July 2015 issue of the journal California Planning & Development Report. In already expensive cities such as London, New York and Santa Barbara, Calif., Fulton writes, the wealthy “drive up home prices by paying premium prices, often for houses they don’t actually occupy very often.”

In a December 2015 study of nine Bay Area counties, the University of California, Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project found “no clear relationship or correlation between building new housing and keeping housing affordable in a particular neighborhood.” The study noted other research showing that market-rate housing may alleviate a housing shortage over a region, but can exacerbate displacement within a given neighborhood. The researchers estimated it would take 50 years for market-rate development in California to make additional housing available to people who earn less than 50 percent of the median income.

The Berkeley study’s recommendations included expediting the building of low-cost housing, coupled with measures like tenants’ rights protections and rent stabilization. Similarly, anti-displacement activists tend to push decommodifying approaches such as rent control, higher taxes on investment properties and increasing public housing stock.

City planning departments favor more market-based solutions. The latest buzzword is “inclusionary zoning,” in which new market-rate housing can be built only if some percentage is affordable.

The standard definition of “affordable” is housing that does not cost more than 30 percent of one’s income. San Francisco then uses the area median income (AMI), currently $82,900 for a single person or $118,400 for a family of four, to calculate affordability. Depending on the project, “affordable” rentals can range anywhere from housing geared to “very low-income” people making up to 55 percent of the AMI to “moderate income” people making 110 percent of the AMI.

San Francisco currently requires 18 percent of units to be affordable (down from 25 percent). Often, developers fulfill the requirement by promising to build a separate affordable housing project later, somewhere else. The effect is that very little affordable housing gets built. As this issue went to press, San Francisco’s official housing website, where people can enter a lottery for affordable rentals, listed no available units.

As the YIMBY movement has grown, there has been “a pretty strong shift toward inclusionary housing,” says Steven Buss, head of Mission YIMBY. “A lot of people within YIMBY … know the market could not possibly serve everyone.” Mission YIMBY, he says, “only shows up for affordable housing projects. … Market-rate developers [in the Mission] don’t need our help.”

When asked about her previous disdain for “subsidized, supervised affordable housing,” Trauss insists her views have never changed. She says the emphasis was on supervised: “The way nonprofit affordable housing is managed can be super disrespectful to the residents.”

Trauss says she supports publicly subsidized housing and rent control for big developers. One YIMBY group, East Bay for Everyone, even wrote a letter of support for overturning California’s statewide restrictions on rent control, though it suggested a “rolling phase-in period.”

But the heart of the YIMBY movement remains pro-development: YIMBYs advocate affordable housing only if it doesn’t conflict with the goal of more housing. Believing it would dampen development, YIMBYs were the loudest voice against Prop C, a June 2016 San Francisco ballot initiative that raised the affordability requirement for new building projects from 12 percent to 25 percent. Trauss and her younger brother, Milo, spoke against the measure. (The younger Trauss serves as the YIMBY Party’s policy director while working as a consultant for GCA Strategies, the self-styled “top public affairs firm” for “mobilizing community support for real estate proposals.”)

In California alone, YIMBYs have backed hundreds of local developments, by Trauss’ estimate. That’s why activists like Zamudio suspect YIMBYs of serving to lend a (false) grassroots face to real estate interests.

For examples, YIMBYs have spoken for several projects by Lennar, the nation’s largest home developer. Lennar has had a run of bad press going back a decade, when it played a major role in the subprime mortgage crisis. Its redevelopment of Hunters Point Shipyard, a Navy Superfund site on San Francisco’s southeast coast, is the subject of an ongoing lawsuit. Residents charge the development’s construction illegally emitted asbestos-laced dust that caused high asthma rates among children in the surrounding, low-income neighborhood.

While developers were not the top overall donors to the YIMBY PACs, they have poured money into YIMBY lobbying on specific measures. The YIMBY group San Francisco Housing Action Coalition raised $1.8 million for its successful campaign opposing a 2015 ballot initiative, Prop I, that would have placed a moratorium on market-rate building in the Mission District.

According to In These Times’ research, at least 45 percent of this money came from the real estate industry, including banks that fund real estate development. Lennar gave $82,500; the firm behind the “Beast on Bryant,” the largest proposed complex in the Mission, gave $137,500; and the head of Maximus, the firm behind the controversial “Monster in the Mission” project, gave $450,000. Prop I was defeated 57 percent to 43 percent.

YIMBY leader Sonja Trauss (center) chats with Palo Alto Councilman Adrian Fine (L) and his wife, Jane (R), at a YIMBY Action fundraising gala Nov. 2, 2017, at San Francisco’s Verdi Club, where Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman was a featured guest. (Photo by Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

In the Mission District’s Clarion Alley, a pedestrian strolls past a mural by the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project. The mural maps no-fault evictions in the city since 1997 and spotlights eight San Franciscans who have fought eviction. (Photo by Joel Angel Juarez)

YIMBYs are also making advances on state politics. Starting in 2016, YIMBY-organized lobbying trips to Sacramento helped push lawmakers to pass what is arguably the first piece of YIMBY legislation in the United States: California’s SB 35. Brian Hanlon helped Democratic state Sen. Scott Wiener draft the bill, which allows for the override of local zoning requirements in cities deemed to have insufficient housing. A March report by the state determined that 97 percent of California cities qualify. In Berkeley, with the support of YIMBY groups, a developer is invoking the law to build 260 apartments on an Ohlone tribe sacred burial site.

Wiener, a YIMBY darling who spoke at YIMBY Action’s November 2017 gala, has continued pushing for statewide overrides of local control. His latest measure, SB 827, drafted by Hanlon, began as a hardline pro-development bill. Critics said the measure would have allowed for the demolition of rent-controlled housing around transit centers, among other controversial provisions. Over time it was tempered with affordable housing requirements. Even so, it was so unpopular that it did not make it out of committee. Members of Wiener’s own party voted it down.

In a number of these battles, the YIMBYs continue to find themselves at odds with social justice-oriented anti-displacement activists. YIMBYs tend to paint such activists as mistakenly allied with NIMBYs. Trauss, in a 2014 presentation, said that YIMBYs aim to “disrupt” the “alliance between rent control advocates and affordable housing advocates.”

Trauss expresses similar sentiments today. She says she believes anti-displacement activists who dislike YIMBYs are misdirecting their energy. “You don’t get affordable housing by opposing market-rate housing. You get it by building affordable housing,” she says. “I’ve never seen as much energy asking the mayor to set aside money for affordable housing. They need to identify the goal and take steps to get them to that goal. … I’m nobody. They could have done everything I did if they wanted.”

Asked about a November 2016 hearing in which she compared Latinx Mission activists to xenophobic Trump supporters, she stood by the comments. “Refusal to build housing is anti-migrant,” she tells In These Times. “And almost every commenter said their opponent was like Trump. ... As long as we’re throwing that around ... I really had to say it.”

Tony Robles, head of the Manilatown Heritage Foundation, a Filipino cultural organization in San Francisco, says YIMBYs “haven’t paid their dues enough to really be talking in the arrogant ways … that they do.” Organizers “put in years here, fighting” for tenant protections that are being whittled away by YIMBYs and their developer funders, he adds.

In the Mission District’s Clarion Alley, a pedestrian strolls past a mural by the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project. The mural maps no-fault evictions in the city since 1997 and spotlights eight San Franciscans who have fought eviction. (Photo by Joel Angel Juarez)

Maria Zamudio of the Plaza 16 Coalition, an anti-displacement group, walks down Clarion Alley in the historically Latinx Mission District. (Photo by Joel Angel Juarez)

Tony Robles is mixed-race. His Black great-grandparents made their way to San Francisco in the 1920s, during the Great Migration. At that time, San Francisco was home to what Robles called the “Spanish Harlem of the West, but Black and Filipino and Japanese, instead of Puerto Rican.”

In the 1950s, the Manilatown neighborhood was the Filipino center of the city, and the site of a large long-term hotel (the “International Hotel”) for Filipino immigrant workers. In the 1970s, San Francisco’s Redevelopment Agency deemed the area “blighted” and slated it for demolition. “This land is too valuable to permit poor people to park on it,” said the agency’s executive director, Justin Herman. In 1977, police forcibly evicted the last of the International Hotel residents.

In 2005, the Manilatown Heritage Foundation helped reclaim the land of the former International Hotel and turned it into 104 units of low-income senior housing. But Robles sees the removal of poor people continuing to play out now.

The real estate website Zillow estimates that in the past five years, the median rental price for a one-bedroom in San Francisco’s historically Latinx Mission District rose from $2,752 to $3,695. Housing activists attribute the rise to the Mission’s market-rate condo boom. As rents have shot up, so have evictions, increasing 67 percent between 2010 and 2015, according to the local Rent Board.

Skin tones are getting lighter, too, as whites replace low-income Latinx people who have been the victims of an eviction plague, whether because they couldn’t afford rising rents or because their landlords found a pretext in order to redevelop. A city-funded report found the neighborhood’s Latinx population will fall from 60 percent in 2000 to 31 percent by 2025 because of gentrification.

Pritzka Rios, 27, was evicted from their Mission apartment in 2017. Rios, who is of Latinx heritage and genderqueer, grew up in California’s Central Valley and was spurned by a family who didn’t accept their gender. They came to the Bay Area for its reputation as more accepting, and the Mission in particular because of its Latinx heritage. Rios became involved in local anti-gentrification activism, like a 2014 action to disrupt an “eviction bootcamp” workshop for landlords put on by real estate lawyers. For seven years, Rios lived in a rent-controlled Latinx co-op home, until their landlord used the “nuisance eviction” justification to evict everyone. The murky “nuisance” law holds a tenant evictable for “low-fault” issues like hanging laundry outdoors, leaving a stroller in the hallway or bringing in another tenant—although, as in Rios’ case, landlords don’t have to disclose the alleged nuisance.

Rios worked a minimum wage job at a hardware store and couldn’t afford to hire a lawyer. “It felt like there was nothing I could do,” says Rios, who describes the situation as the “worst experience in my life.” Like many other Latinx residents of the Mission, Rios was forced to leave the city, eventually landing in Oakland, across the Bay.

In the Mission and places like it, Miriam Zuk of the Urban Displacement Project sees what she describes as “the breaking up of communities in terms of advocacy power, social support. Their neighbor who used to babysit their kids no longer lives there. No one talks about the cultural displacement, feeling like you’re no longer a part of the neighborhood anymore. … It may be harder for young professionals [such as the YIMBY crowd] to understand why that’s a big deal ... that feeling of belonging.”

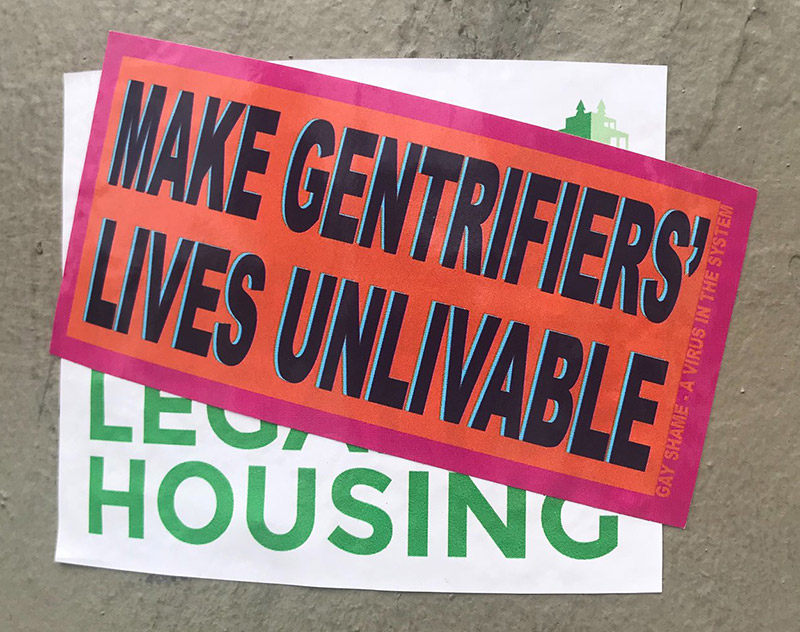

On the streets of the Mission, the hostility over displacement is palpable. Sidewalks are crowded with lines of mostly white and Asian techies headed to Silicon Valley campuses aboard “Google bus” shuttles. A Latinx youth program’s mural that depicted Día de los Muertos icons and the words “Our Culture Is Not For Sale” was deemed “too dark” by a business owner, who preferred a floral-themed mural. The Latinx youth won out, and the floral-themed mural went up in another spot. A day later, it was tagged with graffiti. Soon after, the anti-gentrification group Gay Shame began posting stickers on light poles that read, “MAKE GENTRIFIERS’ LIVES UNLIVABLE.”

A major flashpoint for anti-gentrification anger has been the “Monster in the Mission,” a 10-story, 331-unit building that developer Maximus Real Estate Partners wants to build at the corner of 16th and Mission, next to a busy BART stop. Just 41 of the units would be affordable, with another 49 promised “off-site.” The development has been stalled since 2013, and the Plaza 16 Coalition wants to kill it for good or get a commitment to 100 percent affordability.

In 2015, Trauss and other YIMBYs spoke in favor of the project at public hearings. That year, YIMBYs also threw resources into opposing Prop I, the moratorium on market-rate development that would have halted the Monster. Trauss has since backed away from the Monster, saying that Maximus mishandled the project by threatening access to the BART plaza.

Maximus’ own PR for the project can sound remarkably YIMBY. Last fall, Maximus ran a $46,000 “I Am Not a Monster” ad campaign to promote the development, as part of a $363,200 campaign to build community support. For months, ads ran at the 16th and Mission BART station, featuring local firefighters, small business owners and nurses who, the ads purported, would benefit from the increase in housing stock.

A local elementary school teacher, Nancy Ana Lucero, told the blog Mission Local she’d been tricked into appearing in the campaign by a family friend who was a Maximus rep, who asked her to appear in an “affordable housing” ad. “I was shocked,” she told the blog. “I thought it was really dishonest.” (The rep insists she never misled Lucero.)

Steven Buss of Mission YIMBY is also critical of the Monster: “Building new upscale developments … does raise the rents of nearby buildings. A lot of YIMBYs will say that isn’t true, but it is.” He notes that the area has a lot of single-room occupancy, or SRO, buildings—low-rent, bare-bones housing often rented by the formerly homeless—and the Monster would “put a lot of pressure on SRO owners to redevelop.” Still, he adds, “I’d like to see something get built there. Double the height, get a ton of affordable units in.”

At El Metate, a long-standing burrito restaurant in the Mission District, one table of patrons stands out. It’s the one at which Mission YIMBY is holding its January meeting. One Asian woman and eight white people, including Buss and employees of Airbnb and Uber, sit discussing SB 827 among tables of mostly Spanish-speaking lunchers. Asked if it feels strange to be a table of mostly white tech “migrants” in a Latinx scene, Buss says that yes, it sometimes does.

Buss, 31, has set himself and Mission YIMBY the herculean task of bridging the divide between the YIMBY movement and groups like Plaza 16. On the advice of social-justice activists in his networks who suggest that white people need to learn how to listen, he’s been attending meetings of Latinx anti-displacement groups, sitting quietly in the back. (He also took two months off from his job at Google to volunteer for Trauss’ campaign; she is running for a seat on San Francisco’s board of supervisors.)

Zamudio, of Plaza 16, gets frustrated when housing policy conversations focus on supply and demand rather than the real-world impacts on people, like those in the Mission who have been evicted from their homes or businesses. She says she tries to keep one question in mind: “How deeply grounded is our work in the experience of people in rent-controlled housing and SROs?”

is a San Francisco-based writer who has reported for Al Jazeera, The Nation and VICE. His work also appears in Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison-Industrial Complex and The Long Term: Surviving and Resisting Life in Prison.

This story was supported by the Leonard C. Goodman Institute for Investigative Reporting.

Never miss a story. Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter:

Maria Zamudio of the Plaza 16 Coalition, an anti-displacement group, walks down Clarion Alley in the historically Latinx Mission District. (Photo by Joel Angel Juarez)