|

Devil Inside

Randall Terry

is driving Vermont Republicans into the arms of liberals

By Hans Johnson

Even as invective poured from his mouth in Vermont, Randall Terry felt his ears burning. Earlier this year, the failed New York congressional candidate and founder of the all-but-defunct Operation Rescue arrived in the land of Ben and Jerry to protest a December state Supreme Court ruling endorsing same-sex marriage. Since then, however, Terry has been tagged by Congress for questionable behavior, rebuked by his own pastor for recent marital missteps, and accused of using the Green Mountain State as a backdrop in his own political theater of the absurd. All of this has greatly complicated Terry's makeover from anti-abortion extremist to anti-gay crusader - and highlighted the virtue deficit in the ranks of the Christian Right.

Though hawking a new issue, Terry has retained his trademark gift of gab. Same-sex nuptials, he lectured his New England hosts, should make them "vomit." And since homosexuality is just like "bestiality," he told the Rutland Herald, what's to bar weddings between "a man and a sheep?" He was divinely summoned to Vermont, Terry insists, to elevate "a theocentric view of marriage" - and to intimidate allies of gay rights facing re-election in November.

|

|

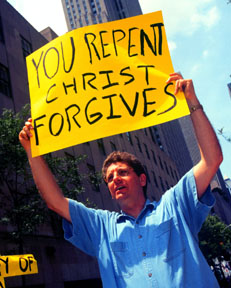

Randall

Terry, founder of the extreme anti-choice group Operation Rescue,

is now aiming his religious crusade at same-sex marriage. Credit:

Richard B. Levine/Newsmakers

|

The state court's verdict cannot be appealed, leaving legislators to hash out the details. While a few staunch liberals have dug in their heels to defend same-sex marriage, many legislators now back a plan to grant recognition of the nation's first statewide civil unions, more sweeping even than domestic partnerships. Terry aims to quash both.

Fat chance, say those now fashioning the civil-union bill. "Like it or not, the Constitution is not based on the Old Testament," says Republican state Rep. Tom Little, chair of the Judiciary Committee. Cribbing a line from the state court ruling, Little told the Los Angeles Times that same-sex couples "are families, and they are entitled to the rights and protections of the Constitution."

Vermont Republicans' attempt to usher Terry out of the state underscores his skill for driving even conservatives into the arms of moderates and liberals. As with his anti-abortion tactics, Terry's anti-gay schtick lends credence to his critics' case for greater legal safeguards from intolerance. With gay-rights foes stuck doing damage control over Terry's credibility gap, his arrival in the state seems the answer to many a progressive's prayer.

In early February, Terry's name came up during congressional debate on bankruptcy reform. Sen. Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) offered an amendment to stop people facing fines or penalties for blocking abortion clinics from using bankruptcy as an escape hatch. As Schumer noted, Terry is Exhibit A among such clinic-blocking scofflaws, owing $1.6 million in judgments to women's groups. Yet in November 1998, he filed for bankruptcy just after having raised thousands of dollars in campaign contributions during his ill-fated bid for a U.S. House seat that same year. Schumer's motion sailed through 80 to 17.

Terry's legal and financial scrapes weren't the only matters making headlines this winter. The press also picked up on a scolding from Daniel J. Little, Terry's longtime minister and leader of the Landmark Church in Binghamton, New York (no relation to the Vermont legislator). In a sharply worded censure letter, Little alleges that Terry has abandoned his wife, Cindy, and their two kids, faulting him for a "pattern of repeated and sinful relationships and conversations with both single and married women." In charging that the censure is "invalid," Terry nonetheless admits to fraying ties with his family, telling the Washington Post, "My marriage problems are personal, painful and private."

Given Terry's image problems, even erstwhile allies in religious circles are urging him to call off the dogs in Vermont. Among Catholics, Bishop Kenneth Angell of Burlington told reporters that the "diocese is in no way affiliated or supportive of Mr. Terry's campaign against same-sex marriage." Even the leading anti-gay group in the fray over marriage, Take It to the People, says that Terry and his handful of followers "do not bring anything positive" and "will only dilute and damage" the process of deliberating policies that respond to the Vermont Supreme Court ruling.

In early March, two key committees in the state House of Representatives approved a civil-union bill, which avoids the word "marriage," but would enshrine for gay couples many of the rights that marriage grants to straight couples. "The design of the bill, we hope, is to create a situation where there's no material difference between [civil unions and marriage] and therefore no constitutional difference between the two," says Little.

During a series of subsequent town meetings, citizens generally gave a thumbs-down to same-sex marriage, but were mixed on the civil- union alternative. In the legislature, the civil-union strategy is also working. On March 15, the state House voted 79-68 to send the bill forward for a final vote.

If legislators go ahead with the civil-union bill - and Gov. Howard Dean signs it, as he has signaled he would - the state will have crossed a political snake pit. Since 1994, 31 states and the federal government have passed laws to block gay marriages. And voters in three states - Alaska, Hawaii and California - have amended their state constitutions in response to lawsuits by same-sex couples seeking marriage certificates.

In Vermont, however, Terry's visibility - and volume - have stolen the thunder from the pious conservatives who have led anti-gay drives elsewhere. Rather than an anti-gay backlash at the polls, Vermont legislators fear an anti-incumbency wave as citizens express impatience at the batch of lawmakers if they miss their chance to craft a speedy resolution to the Supreme Court ruling. Such inaction, says Richard Sears, a Democrat who chairs the Judiciary Committee in the state Senate, "is a liability for any incumbent."

The civil-union bill might also become a campaign-trail guidepost for uneasy gay allies like Al Gore, who supports some aspects of same-sex marriage but shuns the name. If the bill does become state law, gay marriage advocates can thank not only the spirit of civility and tolerance that has governed the debate. They might also throw a bouquet to Randall Terry.

Hans Johnson writes about religion, labor and politics from Washington, where he is assistant editor of Academe magazine.

|

In These Times ©

2000

Vol. 24, No. 10 |