White Lawmakers Are Using Alabama's Racist State Constitution To Keep Black Wages Down

Alabama wrote its 1901 constitution to “establish white supremacy.” Workers in a majority-black city say it’s Jim Crow all over again.

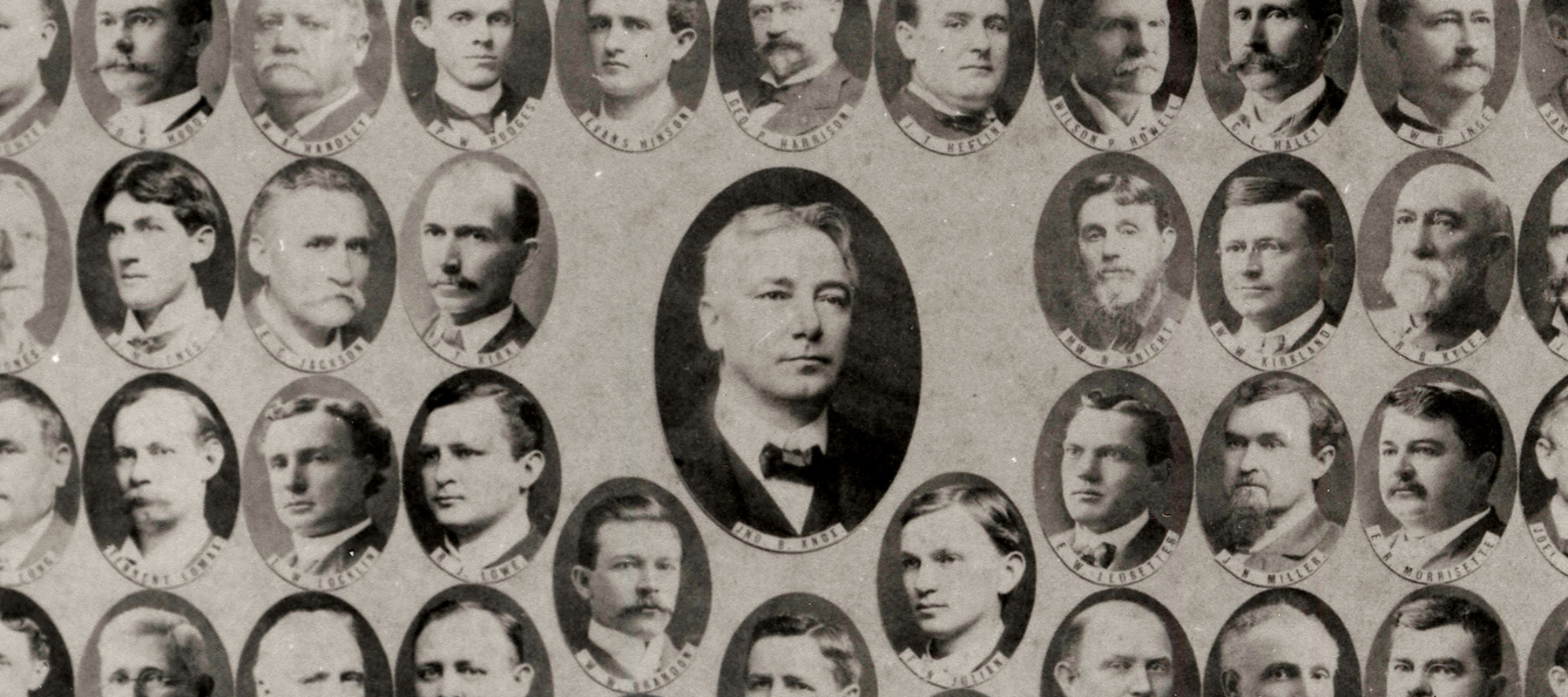

Above: A 1901 convention of Alabama legislators, all white (top right) rewrote the state constitution in order to “establish white supremacy.” The resulting constitution is still in effect. (Alabama Department of Archives and History)

October 23, 2017 | November Issue

Labor Day in Birmingham, Ala., dawned hot and humid—a day for a barbeque or a picnic. But the 100-strong group that gathered in the Five Points West shopping center September 4 had other plans.

As the sun reached its peak, dozens of people wearing “Fight for 15” shirts emblazoned with a raised fist punching through Alabama spilled out of white vans onto the hot asphalt of the parking lot. They stood in small groups, taking selfies and smoking cigarettes. Children held their parents’ hands.

Then Mark Myles, a barrel-chested Fight for $15 organizer with a penchant for doling out hugs, got on a bullhorn. “We are the workers!” he shouted. The crowd enthusiastically echoed him. “The mighty, mighty workers. We’re here for $15—$15 and a union!”

The group marched off to its first destination: McDonald’s. Under the close watch of a handful of police officers and suited-up McDonald’s managers, the crowd gathered in the drive-through lane, joyously shutting it down. “We came to order a raise!” a woman yelled on the bullhorn. Passing cars honked in support. Then the protesters moved on to march through a nearby Burger King and a Popeye’s, shouting slogans and throwing their fists in the air.

On September 4, workers with Fight for $15 in Birmingham rally—again—for a $10.10 wage floor, after the victory was snatched from them by the state. (Photo by Lynsey Weatherspoon)

The day was about demanding higher pay, but politics intermingled with economics. “This is what democracy looks like,” a speaker declared over the bullhorn. “Local governance is very important to your fight.” People with clipboards roamed the crowd looking to update voter registrations.

Just two years ago, these Fight for $15 workers and their allies won a minimum wage increase to $10.10 in Birmingham. It was short-lived. State lawmakers intervened before the law took effect, passing a preemption bill that undid the work of the City Council and the will of its constituents. Since Alabama doesn’t even have its own minimum wage, minimum-wage workers still make the federal wage of just $7.25 an hour.

“We want $10.10, we gonna do it again,” the crowd chanted.

The workers are using protests to pressure corporate employers and state legislators to raise their pay. But they’re not counting on it happening voluntarily. On April 28, 2016, workers in Birmingham filed a lawsuit accusing the state of racial animus and violating the U.S. Constitution’s 14th Amendment guarantee of equal protection.

The lawsuit offers a novel approach in a struggle taking place across the country as blue cities battle red states for self-determination. Republicans often extoll the virtue of local governmental control, but not, it seems, when it comes to progressive change.

Putting Birmingham “in its place”

The state of Alabama was built on slave labor. Enslaved people were essential to the cotton-based economy, and a slave tax was a core source of public revenue for much of the early 1800s. The Civil War and emancipation decimated that economy, and, as in much of the South, the white owner class reacted to Reconstruction with terrorism and violent militias (known as “White Leagues”). By 1874, white Democrats had retaken control of the Alabama government. They quickly rewrote the state constitution to roll back most of the political gains made by unionists and freedpeople during Reconstruction. In 1901, they went even further, creating a new constitution intended to, in the words of the president of the constitutional convention, John B. Knox, “establish white supremacy in this state.”

That constitution remains in effect today. At 388,882 words, it’s the longest still-operative constitution in the world. When they nullified Birmingham’s wage increase—a measure passed by a majority-black City Council in a majority-black city—Alabama lawmakers relied on a clause in this very constitution. The Birmingham workers’ lawsuit argues that the constitution’s accrual of state power was “for the express purpose of denying predominantly African-American communities local control … upon racial grounds.”

The state’s preemption bill passed with only white votes—not a single black lawmaker voted for it. In fact, the entire Alabama Legislative Black Caucus has joined the lawsuit against the state.

“To me, it just looked like race was playing a role,” says Richard Rouco, a local attorney who is representing the plaintiffs in the lawsuit—two workers, the Alabama NAACP and Greater Birmingham Ministries. “Everyone understood it was designed to put Birmingham in its place.”

The lawsuit is still working its way through the court system. If the suit succeeds, it won’t just affect people in Birmingham, or even other cities in Alabama. The potential implications are far larger.

“If we succeed in this case, we’ll show … a way for other cities in the South who face similar legislatures, similar hostility to the interests of the black community, that they might have a way of pushing back,” Rouco says.

The legal options for cities that want to reverse preemption laws are often limited. Thirty-nine states follow a doctrine known as “Dillon’s Rule,” codified a century ago. Dillon’s Rule holds that cities are granted powers only by their states, and that states can revoke those powers. Some cities have successfully fought back against these laws, but on narrow technical grounds. The city of St. Louis, for example, successfully defended its right to raise its minimum wage by arguing that Missouri’s 1998 preemption law was filed incorrectly. In response, the state legislature simply amended the state constitution—correctly, this time—to deny cities authority.

But a racial discrimination argument could override Dillon’s Rule. And it may not be that hard to make, even outside the South. According to a recent analysis by the Partnership for Working Families, seven predominantly white legislatures have recently passed legislation that blocks a city with a large African-American population from raising its own wage. While Southern states such as Alabama and Georgia make the list, so do Ohio and Missouri.

Advocates see it as a continuation of Jim Crow policies that imposed white rule on black communities, thus diminishing black people’s chances of economic advancement. “It’s really preserving a legacy where communities of color are not able to pass local policy,” says Nikki Fortunato Bas, executive director of the Partnership for Working Families.

“It’s a pretty disturbing trend,” Bas adds. “State interference is more than about just politics; in many cases, it’s also about racial justice.”

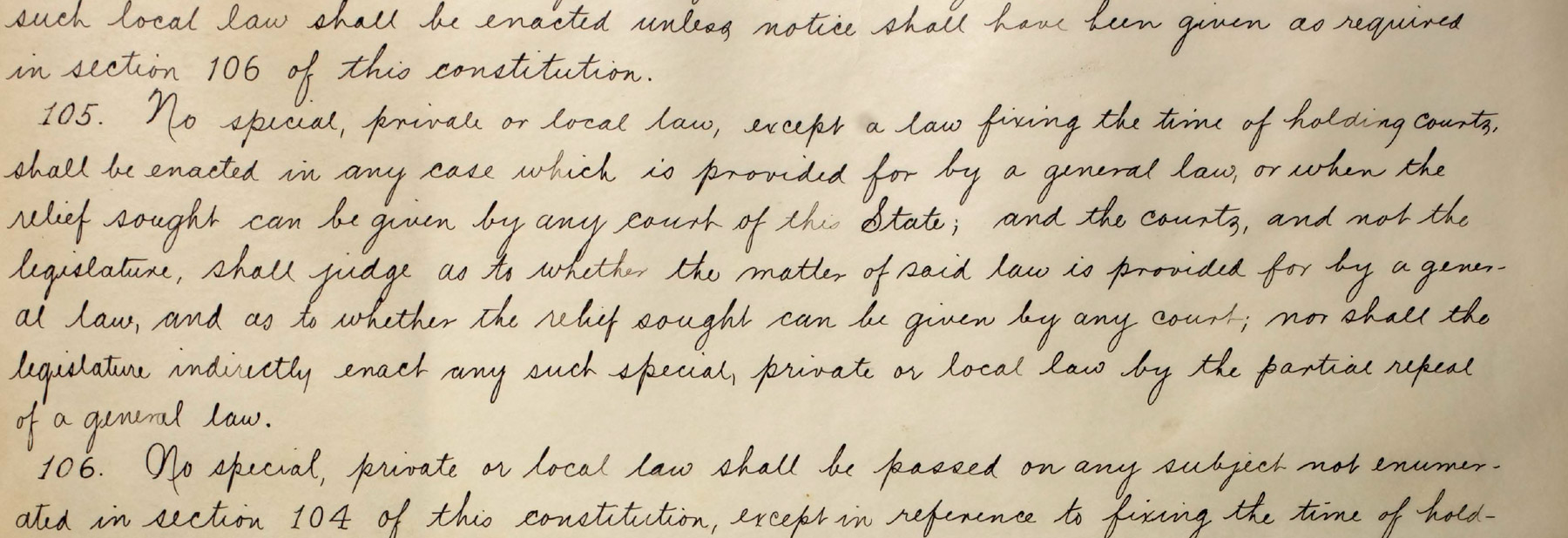

Most of the dozens of provisions of the 1901 state constitution intended to disenfranchise black and low-income white voters have been struck down, but language that centralizes economic control in the hands of state lawmakers remains on the books. (Alabama Department of Archives and History)

The Fight for $15 and self-rule

Organizations such as Greater Birmingham Ministries have worked since the late 1990s to raise wages in the city. But it wasn’t until Birmingham’s chapter of Fight for $15, called Raise Up for $15, got going in 2015 that they started to see action. “The glue that held that together was the weight of the authenticity of the Fight for $15 workers,” says Scott Douglas, executive director of Greater Birmingham Ministries.

Raise Up for $15, SEIU and Greater Birmingham Ministries staged a number of rallies and demonstrations in support of a wage increase. In April 2015 the Birmingham City Council passed a resolution calling on the Alabama legislature to pass a statewide minimum wage of at least $10 an hour. The state never responded.

“As far as we can tell, they basically put that in the wastebasket,” says Rouco.

So activists targeted the city government, demanding it raise workers’ minimum wage to $10.10. It’s a tactic that’s increasingly taken root across the country, particularly as Congress has failed to raise the federal floor for eight years. Before 2012, only five localities had passed their own minimum wage laws. Today, 39 cities and counties have passed them, with 20 going as high as $15 an hour.

At first, Birmingham lawmakers protested, arguing that they didn’t have the legal authority to pass their own minimum wage. But nothing in the state constitution said they couldn’t. Then the councilors voted to raise wages—for themselves, lifting their base pay from $15,000 to $50,000. “That lessened the resistance,” says Douglas with a laugh.

In August 2015, the council passed an ordinance to increase the wage floor to $10.10 within two years, making it the first city in the South to raise its minimum wage.

Sherrette Spicer, a Raise Up for $15 organizer who works at a local Cracker Barrel, was outside the City Council when it happened. “There were some moments of elation,” she says. “We were excited.”

Derrick Miller was one of the low-wage workers who stood to get a raise. At the time that the City Council passed the increase, he was working at Hardee’s, making $7.65 an hour. Miller, 36, has a smile that lights up his face and pushes up the apples of his cheeks toward his soft brown eyes.

But his smile covers hardships. He has four children, ages 4 to 16. And he’s always worked in jobs where he earned close to the minimum wage, making it a challenge to get by and provide for his kids.

So when he found out that the City Council had passed the raise, he recalls, grinning, “I tell everybody everything gonna be alright. I’m telling my children’s mom everything gonna be alright now.”

He was looking forward to being able to afford a car on $10.10 an hour—something he desperately needs, living far from mass transit. But the excitement in Birmingham didn’t last.

Derrick Miller was struggling to get by on $7.65 an hour when the $10.10 minimum passed. He recalls, “I tell everybody everything gonna be alright, I’m telling my children’s mom everything gonna be alright now.” (Photo by Lynsey Weatherspoon)

“We started almost immediately to get rumors from the legislature that they gonna pass a bill to annul it,” Douglas says.

On the first day of the next legislative session, Feb. 9, 2016, a bill was introduced by Rep. David Faulkner (R), a white lawmaker who represents the wealthiest community in the state, which is over 96 percent white. Faulkner’s bill didn’t just prevent future minimum wage increases by cities and counties. Nor did it halt at rolling back the victory in Birmingham. It said that only the state can regulate private employers’ wages and benefits, taking that power completely out of city and county governments’ hands.

Faulkner, an attorney who represents Home Depot and has served on several local Chambers of Commerce, explained the bill as a response to “an attack by labor unions coming in [and] getting cities to raise minimum wages.”

The bill made it from introduction to passage in 16 days. “Frankly unprecedented,” is how Rouco describes it. The only similar legislation the state had ever considered was a bill in 2013 prohibiting municipalities from regulating guns. This was far broader.

The $10.10 minimum never saw the light of day. Miller found out what had happened to his pending raise while watching the news. “It was a shock, just like a slap in the face,” he says.

He has yet to make $10.10 an hour. Instead, after traveling to join a mass Fight for $15 demonstration in front of McDonald’s headquarters in Illinois, he was fired from Hardee’s, where he had worked for five years. (Hardee’s did not return a request for comment.)

After that, “everything changed,” he says.

When he talks about the next phase of his life, all traces of a smile fade from his face and he stares down at his lap. He and the mother of his children lost their house and had to move in with her mother. Between the stress of that transition and his struggle to find a new job, his partner ended the relationship after eight years and three kids together.

“She thought I was trying to, you know, sit around and not try to find a job,” he says. “That ain’t what it was.”

It was an incredibly difficult time. “My grandmother like, ‘You ain’t the same person,’ ” he recalls. It took him some time before he could “laugh and joke and be [himself].”

Today, he still lives with his grandmother in a home crowded with his grade-school trophies and class photos. After a year of unemployment, he got a new job working at McDonald’s for $8 an hour. The pride he takes in his work is clear. He’s quick to boast of how well he handled the breakfast rush at Hardee’s. When he wasn’t getting enough hours at McDonald’s, he says, he “started working harder, faster,” learning how to do extra tasks.

But he still struggles to get by on $8 an hour, even full time. “I want to work, but I don’t make no money,” he says. “You might be alright making $7.50 for yourself, but if you got children, oh lord.”

His dreams of going back to school to get a better-paying job still hinge on being able to afford a car. His grandmother, who is 81, has to drive him to and from work, and he’s nervous about making her drive farther at night. He sees his kids on his days off, but it’s difficult without a car, and it’s never enough time. “I don’t want to be away from my family,” he says.

Miller is one of an estimated 40,000 workers who stood to benefit from Birmingham’s $10.10 minimum wage. That’s a big number in a city of about 210,000.

A page from ALEC

State legislators didn’t come up with the idea of preemption all by themselves. After Colorado and Louisiana passed minimum wage preemption laws in the late 1990s, the American Legislative Exchange Council—a corporate-backed conservative coalition funded by the likes of Exxon, Koch Industries and AT&T that spreads model legislation on its pet issues—took up the charge. In 2001, ALEC came up with what it calls the Living Wage Mandate Preemption Act. It was a template for states to block cities and counties from raising pay in their own communities. It didn’t set a floor below which cities couldn’t go; it set a ceiling based on state law.

States took ALEC up on its idea, often in response to campaigns to raise wages in places such as Atlanta and San Antonio. Four states passed minimum wage preemption laws between 2002 and 2005. But activity mostly petered out after that.

Then, in 2011, SEIU launched the Fight for $15, a nationwide campaign for $15 and a union. It made headlines with the first-ever fast food strike in 2012, a one-day action that has since been repeated in hundreds of cities across the country. Workers have convinced a number of city governments to take action on the minimum wage.

But the movement to increase local wages coincided with conservative lawmakers seizing control of statehouses. In the 2010 midterm elections, Republicans won more than 680 seats, the most since 1938, taking complete control of government in 21 states.

ALEC decided to make another push on preemption in 2013 and found a warm reception among Republican lawmakers in state legislatures and governorships. “All of a sudden, we saw a slew of states deciding to pass preemption laws [that] looked very similar to its model bill,” says Marni von Wilpert, associate labor counsel at the Economic Policy Institute. Between 2011 and 2013, 105 preemption bills undermining wages were introduced in statehouses, about two-thirds of which were sponsored or co-sponsored by legislators who were affiliated with ALEC.

At least 25 states have now instituted laws that usurp city and county power to take action on their own minimum wages. More than half have passed since 2013. Five states joined the list in 2016 alone, with three more this year so far.

And preemption laws are becoming both more expansive and more punitive. “What we’ve seen is preemption on overdrive,” says Lisa Graves, executive director of the Center for Media and Democracy. It’s not just about the minimum wage anymore; states have blocked cities from taking action on issues such as paid sick leave, anti-discrimination rules, fracking, and even the regulation of plastic bags and e-cigarettes.

States have also started enacting what anti-preemption advocates dub “super preemption”: legislation that allows state lawmakers to punish local governments for bills that conflict with state law. In some, such as Florida and Indiana, local officials can be held personally liable if they vote for laws and refuse to rescind them, including being sued, fined or removed from office. In others, such as Arizona, the state has threatened to strip cities of funding.

There’s another innovation in the current wave of preemption laws: Some have been implemented after a city already raised its wage. In St. Louis, workers just had their pay increases taken away.

Wanda Rogers works at a McDonald’s in St. Louis. The 43-year-old lives in a two-bedroom apartment in low-income housing with her daughter and two grandchildren. She worries that her housing situation is hurting the children. “We have to constantly watch for mice, because we have mice everywhere, starting to climb into the bed,” she says. She won’t let her grandchildren play outside because she’s afraid of violence and crime. Yet she can’t afford to move anywhere else; she can barely afford to keep this place.

St. Louis’ $10 an hour minimum wage ordinance meant that McDonald’s worker Wanda Miller no longer had to choose between paying “rent, my gas and light [or] food.” Then the state revoked it. (Photo by courtesy of Wanda Rogers)

These worries began to melt away after her City Council implemented a minimum wage increase in 2015, which brought her pay from $7.70 to $10 an hour in May of this year. “It was a great, great big help,” she says. “It gave me 200 more dollars on my check, which made me not have to … decide how I’m going to pay my bills or if I’m going to pay my rent, my gas and light [or] food.”

But she’s lost that raise, along with about 35,000 other St. Louis residents. The Missouri legislature passed a law earlier this year that blocks cities from increasing their minimum wages. It went into effect in August, lowering the wage floor in St. Louis back to $7.70 and reversing raises that employees had already gotten.

Organizers came up with a new tactic to try to preserve the city’s higher pay: a campaign called Save the Raise that pressures local employers to continue paying $10 an hour despite what the law says. So far 140 have signed on, including Casey Miller, who owns two restaurants and a record store with her husband. “When you’re a small business you can’t go hide up in an office,” she says. “I couldn’t take that money away from my employees and just keep coming around.”

She’s watched her 40 or so workers turn around and spend their wages in the neighborhood, bolstering sales for everyone. “I feel like it’s good for business, it’s good for community, it’s good for my employees,” she says.

But big corporate employers such as McDonald’s, where Rogers works, haven’t gotten on board. “We’ll go back to struggling again,” Rogers says. “If I could keep my raise, that could help me get out of here.

“I wish people at the top making all this big money … could come see my apartment, spend one night in my apartment,” she adds.

McDonald’s did not respond to a request for comment.

Cities may have few tools in their toolbox to undo passed state laws—putting a heavy emphasis on preventing them in the first place. A new initiative launched in January aims to coordinate efforts across the country: the Campaign to Defend Local Solutions, the brainchild of Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, who was personally sued by the gun lobby for refusing to repeal a ban on shooting guns in public parks.

“We felt like there was … a need for local elected officials and local governments around the country to push back against the trend of preemption,” says Mike Alfano, the campaign manager. “The folks pushing these preemption laws are so coordinated and coalesced that there’s no other way to successfully slow it down or ultimately defeat it.” The organization is focused on educating the public on this little-noticed trend, as well as supporting legal efforts against preemption.

But it will take significant work to raise its profile enough to make an impact. “The question is which moves these state electeds more: the money [from ALEC’s corporate interests] or the organizing and the shaming from workers and people in their communities?” says Tsedeye Gebreselassie, a senior staff attorney at the National Employment Law Project.

An answer is urgently needed. Reminders of the civil rights movement, which based many of its actions and strategy sessions in Birmingham, are scattered throughout the city. The A.G. Gaston motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders held their strategy sessions, is just a few blocks from the 16th St. Baptist Church, where a bomb planted by the KKK killed four young girls in 1963. They’re also a reminder of the importance of legislative change for improving the well-being of people of color.

“In an era when the federal government is going through a phase of being nonresponsive and non-responsible, then there are going to be increasing efforts to win and defend victories at the local level,” Douglas says.

Everyone is still waiting to see whether local democracy can prevail.

is an independent journalist writing about the economy. She is a contributing op-ed writer at the New York Times, has written for The New Republic, The Nation, the Washington Post, The New York Daily News, New York magazine and Slate, and has appeared on ABC, CBS, MSNBC and NPR. She won a 2016 Exceptional Merit in Media Award from the National Women’s Political Caucus.

Above: “We are the workers! The mighty mighty workers!” shouts organizer Mark Myles at the Fight for $15 Labor Day protest in Birmingham. (Photo by Lynsey Weatherspoon)

Want to stay up to date with the latest news on movements for racial and economic justice? Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter: